Grieving Faraz’s Death: The Bay Area Closure

By Ali Hasan Cemendtaur

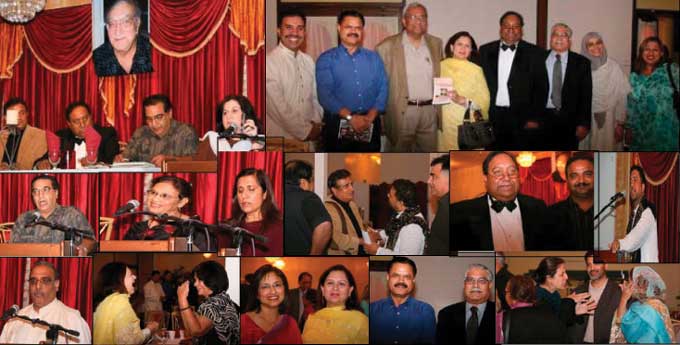

Pictures above: Glimpses of the program. A strong lineup of people paid tribute to Ahmad Faraz in Friday’s program

Times change and with changing times powerful themes defining an era fade, erode, and ultimately go extinct. There was a time when poets in South Asia used to write in Farsi. Muhammad Iqbal was definitely the last notable poet of that conviction. As Farsi faded among the South Asian literati, Urdu gained grounds.

Muslims of South Asia had a natural affinity towards languages written in the script of their sacred book. There are eight such languages, but among those eight only Urdu was used as a communication tool between speakers of different tongues. And Urdu had that status because it grew under the Mughal court.

After 1857 two prominent Muslim educational institutions, Aligarh Muslim University and DarUlUloom Deoband, were established, both in the heartland of Urdu. Muslims throughout the length and breadth of South Asia started sending their children to study at these two centers of learning.

Urdu started emerging as "the" language of Muslims of South Asia. Even Muslims living outside the lands of Urdu — UP, Hyderabad Daccan, Bihar, and Punjab — considered Urdu to be their language. Ahmad Faraz certainly belonged to that era, or probably to the tail end of that era because among many communities the love for Urdu was lost after the creation of Pakistan.

In Pakistan Urdu enjoys official patronage, and hence is associated with the state. Consequently, as consecutive Pakistani governments failed in meeting the expectations of the people, the state along with all its associations, including Urdu, was deemed condemnable by the disadvantaged communities. If Faraz were born in 1831 instead of 1931 he would have written poetry in Farsi; and if he were born in this age he probably would have been writing in English.

Most writers and poets have to wait for their death to reach a wide level of recognition. That was certainly not the case with Ahmad Faraz. He rose to fame in the 70s, and especially after Mehdi Hasan sang Faraz’s “Ranjish hi sahee, dil hi dukhanay kay liay aa.” After the death of Faiz, Ahmad Faraz was considered the reigning king of Urdu poetry. As Faraz’s fans started spreading themselves around the globe, Faraz started making international trips to be with them. In every major city of the Middle East, Europe, North America, and Australia, with a sizable population of Urdu poetry lovers, Faraz has fans who hosted him, went to excursions with him, ate with him, and talked to him at great lengths. There is hardly any other South Asian celebrity who can claim a personal relationship of this magnitude with his or her fans.

With personal relationship comes personal grief. When Faraz died in August of this year his fans in San Francisco Bay Area who had seen him very closely considered Faraz’s death a personal loss. The need was felt for a gathering of fans to mourn Faraz's death and bring a closure to the grief. After much deliberation such a program was arranged by poet Farooq Taraz, prominent Bay Area organizer Annie Akhter, and their friends on October 24 at the Mehran Restaurant in Newark. Chicago-based poet Iftikhar Naseem presided over the gathering and Zafar Abbas, Los Angeles-based editor of Urdu Times, was the guest of honor.

Annie Akhter acted as the master of ceremony, and the role was befitting because among Faraz’s fans in the San Francisco Bay Area, Annie probably had the deepest personal relationship with the famous poet. Two distinguished Pakistani writers, Kishwar Naheed and Iftikhar Arif, called during the program and shared with the audience their thoughts related to Faraz, his life, and poetry.

A strong lineup of people paid tribute to Ahmad Faraz in Friday’s program: after giving a brief account of his personal impressions of Faraz, political activist Ijaz Syed read an essay written by Bay Area writer Moazzam Sheikh; Urdu teacher Hamida Bano Chopra recounted the time she spent with Faraz while attending a conference in Turkey; poetess Rubina Geena paid a tribute in verse to the deceased poet; Atiya Hai sang two popular ghazals of Faraz; poetess Mehnaz Naqvi remembered her encounters with Faraz; Sukhdev Sahil sang two ghazals; Naveeda Ellahi recounted her light conversations with Faraz; Farooq Taraz described his over 15 years’ association with Ahmad Faraz; Zafar Abbas described how he saw Faraz; and Iftikhar Naseem shared with the audience memories of Faraz’s last days in the US. The last three also read their own poetry.

The overall structure of the program was well thought of --speeches and songs were interjected with screenings of Faraz’s video-taped interviews and recitations. A slide show projecting on a side screen Faraz’s pictures with his fans ran continuously throughout the program.

In the interest of negating the impression that when it comes to matters of government overseas Pakistanis are lavish in criticism and stingy in praise, Faraz’s fans must appreciate the efforts of the Pakistani embassy in making arrangements to fly Ahmad Faraz back to Pakistan after he was hospitalized in Chicago. More recently, the embassy has also provided praiseworthy moral support to Dr. Aafia Siddiqui, Nayyar Zaidi, and Alamgir.

Pictures by Nagesh Avadhany

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------