Dr Akbar Ahmed’s Poetry Shows Path to Peace

By Aja Anderson

American University

Washington, DC

O n the eve of graduation from high school, in the spring of 2004, I gave a “senior sermon” from the pulpit of my childhood Lutheran Church. As an inquisitive student, I had begun to struggle with the absolutism of the religious curriculum taught in my Catholic school, and could not prevent myself from questioning why one tradition should be placed above another, or how God could not, by any name, remain divine.

I had begun to seek what was seeking me, as Rumi wrote, but independent of creed or convention. St. James, known in the community as a progressive spiritual space, was an appropriate venue to profess my firm belief that when it came to God, all paths led to the summit of the mighty mountain; all rivers wound down to the vast, imponderable sea. I did not realize at the time that I was echoing the philosophy of my future professor and employer, Ambassador Akbar Ahmed, in the tradition of the Sufi mystics.

Seven years later, I found myself sitting in the front row, on two separate evenings and in two different locations as my boss and mentor read “The Path,” contemplating the lines that continued to feel so true:

“Yet others find other paths/I wish them all Godspeed/For all of them are part of the ‘nations and tribes’/That the Qur’an tells me I must love/So that I can love my God. “

Those words echoed the pluralistic ideal which had become central to my studies and my life, and I felt in good company with the students, teachers, and members of the community who had come to listen to Dr Ahmed recite from his new book of poetry, Suspended Somewhere Between. He described his writing as cathartic, raw, and honest outpourings of his deepest thoughts on love and loss, religion and country, violence and peace.

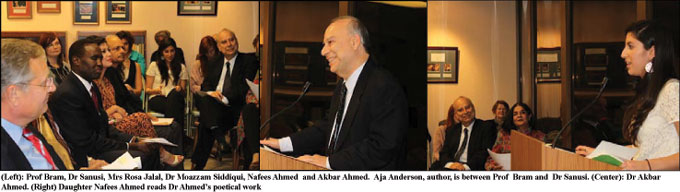

We assembled first on the evening of 1 November at American University. At the university, the audience was mainly students of poetry, keen for an inner look into the genius behind the craft. One Iranian student stood up during the Q&A, thanking Dr. Ahmed profusely for his poem “To My Mother.” “I am in the clouds!” she gushed. The poem had been read both by Dr. Ahmed in English and his close friend Dr. Moazzam Siddiqi, a fellow poet and linguist, in Urdu. The student was moved, she said, not only by the beauty of the verse, but also by hearing it in two languages. She, like the rest of us, was transported across cultures by the weight of Dr. Ahmed’s words, which pushed listeners above diverse backgrounds and beliefs to the common ground of love, compassion, and understanding.

Two nights later, driving north on Massachusetts Ave, I hardly noticed the seamless shift from District of Columbia into Bethesda, Maryland, to visit the Gandhi Memorial Center. It was, as many guests expressed, like coming home. It served as the perfect venue for Muslim, Christian, Jew, and Hindu to meet. We welcomed diplomats from the Embassies of Israel, Indonesia, and Sri Lanka, friends from Pakistan, Afghanistan, Sudan, and colleagues from the DC metro region. As each reader, from the Madame Ambassador of Indonesia Rosa Djalal, to Dr. Mohammed Elsanousi of ISNA, performed their interpretation of Dr. Ahmed’s poems to a standing room only crowd, I recalled the words of Gandhi, cited that evening by Srimati Kamala, the Center’s founder:

“I have known no distinction between relatives and strangers, countrymen and foreigners, white and colored, Hindus and Indians of other faiths whether Mussalmans, Parsees, Christians or Jews. I may say that my heart has been incapable of making any such distinctions.”

It was a significant illustration of Dr. Ahmed’s commitment to interfaith cooperation to have held a reading of his work at the Gandhi Center, both because of his Pakistani heritage and Muslim religion, and because we were joined by so many of diverse origin, and who, if we stuck by political animosities, should not have been in the same room at all. However art, and specifically poetry, has the ability to serve as much more than a means of communication; it can be an instrument of faith, a bridge between adversaries, an agent of peace.

A feeling of kinship permeated both performances, and I have carried that spirit with me for days. It seems every waking minute of modern human existence is full of distractions. Our attention span is little more than thirty seconds, which is just enough time to absorb the latest diet fad, juiciest scandal, or most outrageous political posturing. Is it difficult to sift through the white noise, put down the PDA’s, and take a moment to connect with ourselves, our companions, and our God. Making time for introspection, much less spiritual communion is often the last item in a litany of pesky to-do’s. Dr. Ahmed’s poetry allowed us a “time-out” to do exactly that: look inward, examine our own beliefs, and bond with each other, regardless of race, religion or country.

“I am the place/where creation is working itself out.” So writes the Swedish, Nobel Prize winning poet Tomas Transtromer. I felt that all of us, both at the university and at the Gandhi Center, were fellow pilgrims on the journey to discover not only the deepest recesses of our own faith and relationship to God, but how we could transcend that which might irrevocably divide us, in the footsteps of our shared prophets, with the poetry of Dr. Akbar Ahmed to guide us.

(Aja Anderson is Program Coordinator of the Ibn Khaldun Chair of Islamic Studies at American University’s School of International Service in Washington, DC. She serves as Chief of Staff for Ambassador Akbar Ahmed)

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------