Neither Submissive nor Invisible: Smashing Stereotypes of Muslim Women at American University

By Aja Anderson

American University

Washington, DC

Washington, DC: Students sat rapt as the glamorous Madame Ambassador addressed the class; she was soft spoken, but passionate and articulate. She was not veiled; rather, she wore Christian Louboutin pumps. This was not the image the young Americans called to mind when they thought of a “Muslim woman.”

Undergraduates at American University are citizens of the world; culturally sensitive, well educated, and well traveled. Yet even they struggle with diffusing stereotypes that have been entrenched in Western consciousness in the post-9/11 world: that the Qur’an advocates for violence and the mistreatment of women; that there are no moderate voices in Islam; and that to be a Muslim woman is to be oppressed.

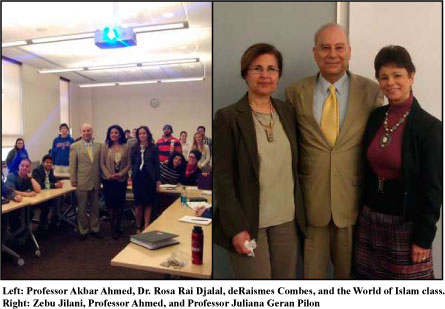

These misconceptions were shattered for Ambassador Dr. Akbar Ahmed’s World of Islam class on the Friday following International Women’s Day in March 2012. Visited by three intelligent and fascinating women, the students were privy to lessons from the field: how real Muslim women are living in Indonesia and Pakistan, and that it is a mistake to make broad generalizations about the role of Islam’s women based on individual cases or even individual cultures.

Dr. Rosa Rai Djalal, wife of the Indonesian Ambassador and President of the DC Muslim Women’s Association (MWA), Zebu Jilani, director of the Swat Relief Initiative (SRI), and Dr. Juliana Geran Pilon, author and professor at the Institute of World Politics, spoke to the class of 60 for nearly three hours, covering a diverse range of topics from development and humanitarian work to the superiority of the beaches of Bali. These women were neither frivolous nor passive; they represented the best combination of Eastern and Western traditions.

Professor Ahmed opened the session, posing questions to the students that contrasted what he identified as “ideal Islam vs actual Islam.” He pointed out that Islam was the first religious tradition to afford important rights to women, such as inheriting property, initiating divorce, and owning businesses. “No other civilization [would give] these rights for 1000 years,” he said.

As Muslims well know, some of the most crucial figures in their early history were women. Khadija, the first convert to Islam, was the Prophet Muhammad’s wife and a successful businesswoman in her own right. Fatima, the Prophet’s daughter, was a powerful political voice in the Ahl al Bayt (family of the Prophet), and key to the sacred lineage of Islam’s most important family. The Prophet’s youngest wife, Aisha, was a formidable scholar, and is responsible for preserving his sayings and doings. If not for her commitment to the historic record, Islam would have lost invaluable insight into the life and times of the Prophet.

Professor Ahmed went on to lament the atrocities many Muslim women currently face: honor killings, female genital mutilation, and acid attacks. None of these are Islamic traditions. As he gave the floor to Dr Djalal, one student raised her hand eagerly, asking “why are Muslim women facing these challenges?” Her earnest query reflected the focused attention of the room, which included Muslim students, who were all bent on enlightenment.

Addressing the class, Dr. Djalal was a captivating sight. Her enthusiasm and sincerity were palpable; her fashion sense impeccable. As the President of the MWA, she is often greeted with surprise, as she does not fit the typical profile of a Muslim woman. “In response, I usually ask, ‘what do you expect me to look like?’ ” she said. “I consider myself a typical Muslim woman. I pray, I fast, I study the Qur’an, and most importantly I adhere to the five Pillars of Islam.” Dr. Djalal refuses to conform to a specific image, as stereotypes of what she should look like or act do not match reality.

Djalal drove home a critical point on the subject of veiling: that it is an individual choice. She referenced diplomats in her embassy who proudly wear the scarf as a symbol of piety. The Indonesian government has no say in how these women dress. Acknowledging that women do face discrimination in other countries, she joked, “Believe me, there is nothing in [the] Holy Qur’an that says women cannot drive a car.” Touching on the topic of acid burning and stoning, Djalal attested that these were the result of local culture, societal habits, and political manipulation in the context of a patriarchal society. She went on to highlight Indonesia’s acceptance of all people, regardless of religious beliefs. “Your God is your God,” she said bluntly.

During the Q&A, an American ROTC student asked Dr Djalal whether she, as a voice for Muslim women, had an opinion on America’s role in the quest for greater female liberation in the Middle East. Djalal smiled and said, “First, thank you. Thank you for what you have done for Egypt, Tunisia, and Iraq.” She went on to highlight how beneficial US involvement has been, providing opportunities for education, technological advancement, and most significantly, teaching people that they have a voice, and the right to use it. Her appreciation reverberated throughout the room: few of us had ever heard a Muslim speaker thank America so profusely.

Following the Madame Ambassador, Zebu Jilani spoke, exuding confidence and conviction. She described her work in Swat, modestly acknowledging that she is the only NGO CEO who is on the ground in routine, rather than dictating demands from the comfort of a far away office. Her discussion of the refugees of the 2011 floods in Swat motivated many students to inquire about volunteer opportunities with SRI. Jilani stressed the people’s great desire for education for themselves, but especially for their children. She noted that it was only through education that the society would move forward, culturally and economically.

Jilani told an interesting story to highlight the dichotomy between religious text and social custom. Her driver during her trips to Swat was a pious man with an impressive beard. There is no beard in the Qur’an, Jilani pointed out. Piety is not best exemplified through facial hair. She asked him whether he had given any inheritance to his daughters, which is a prescription of the holy book of Islam. He replied that he had not. Recently, Zebu received a phone call from her driver, who was in tears at the end of the line. “I did as you asked;” he moaned, “and now my sons have thrown me out!” The class laughed, but I was struck by the dark side of the comedy: context matters little when society punishes you for doing the right thing.

At the end of the class, Professor Ahmed invited Professor Pilon to the podium to give a summary of the conversation thus far. She took a practical approach. “What can we do about this?” she asked, meaning, how do we catch the world up to the egalitarian values prescribed 1400 years ago? The answer had been repeated by all the women throughout the class: education. This was the job not only of Muslim women, but of the rest of the world as well.

“What have we learned?” asked Professor Pilon. “That the holy book of Islam is not misogynist: it does not consider females inferior to males.” Quoting from the Qur’an, Pilon substantiated this point: “And it is for women to act as the husbands act by them, in all fairness.” This concept of egalitarianism and reciprocity was a new one for many of the students.

Later that day, the Madame Ambassador sent a beautiful batik printed card to Professor Ahmed expressing her delight at having been a part of the lecture. Calling Ahmed a “great mentor” and “inspiring,” she praised the class, saying, “I really enjoyed everything; the class, the students, the ambience, the questions and the sensitive and positive energy that spread around the classroom.”

It truly was an instructive and optimistic afternoon. The women acknowledged the problems that exist, but stood up for their religion, defending it against erroneous accusation. They offered constructive solutions, pointing out that education is the key to making a difference in every instance of inequality. What better way to celebrate Women’s History Month than to receive such knowledgeable, accomplished female scholars in our class?

(Aja Anderson is the Program Coordinator and Chief of Staff for the Ibn Khaldun Chair of Islamic Studies in the School of International Relations at American University in Washington, DC)

Back to Pakistanlink Homepage

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------