Washington DC Synagogue Leader Aims to Bridge the Jewish-Muslim Divide

By Matthew Agar

American University School of International Service

Washington, DC

In Judaism, there is the phrase Tikkun Olam, or “Repair Our World.” Jews across the world invoke this phrase with a desire to mend disputes between their communities and non-Jewish communities.

In light of the recent violence in Israel and Palestine, where a cycle of stabbings and retaliatory attacks plague both sides, the notion of repairing the world of Jewish-Muslim relations seems as far from reach as ever before. Followers of these two Abrahamic religions, whose basic teachings preach compassion, understanding, and the pursuit of knowledge between and beyond followers of one God, are denying the humanity of one another. For this reason, mending ties between Jews and Muslims is critical. Only through thoughtful dialogue and discourse on our shared values can we repair our world.

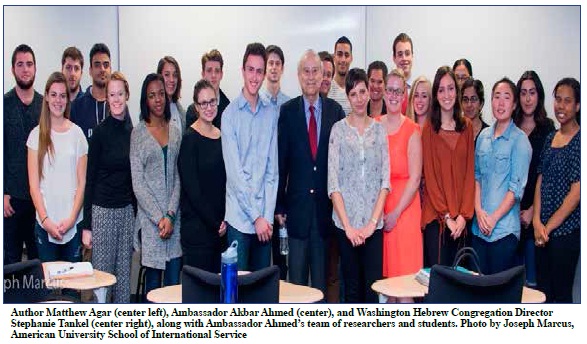

In a timely fashion on this subject, I had the pleasure to attend a lecture on November 6 in my “World of Islam” class at American University in Washington, DC. Twenty-four bright, young, and optimistic university students and Ambassador Akbar Ahmed, the Ibn Khaldun Chair of Islamic Studies at American University and former Pakistani High Commissioner to the UK and Ireland, had the opportunity to hear how one Jewish leader, Washington Hebrew Congregation Director of Religious School, Stephanie Tankel, seeks to build bonds between these Muslims and Jews.

Tankel’s discussion flowed from three shared themes between the two faiths: prayer, practice, and place. Both Islam and Judaism engage in prayer based upon the Old Testament. Each religion has common dietary practices of Halal and Kosher. Lastly, and most significant to the wave of violence engulfing the two communities, they have an affinity for places of significance, with a sanctuary of hope, and at the moment, divisiveness, in Jerusalem.

This process of connecting Islam and Judaism in a single narrative was particularly insightful. As a liberal American Jew from New York, I grew up in a household where Judaism and the Jewish community was seen as a world apart from the non-Jewish world. This flies in the face of what all Abrahamic faiths teach us: to embrace and love your neighbors. It also contradicts the ideals of the pluralistic, democratic country I love with all my heart.

To my parents, our people may be assimilated; we may be open minded; we may even have frequent and intimate interactions with people of different backgrounds. However, in their eyes, and in the eyes of many American Jews, we can never make a full transition to wholeheartedly embrace those many Jews affectionately or not refer to in Yiddish as ‘Goyim’, or those who are not Jewish. There is still too much misunderstanding, mistrust, and blatant anti-Semitism towards the Jewish people to completely drop our guard. Even in my interactions with non-Jewish acquaintances at American University, I was once innocently assumed to have horns and a tail per a caricature of my Jewishness. It is best to play it safe and not engage in dialogue at all for fear of being too vulnerable.

Stephanie argues otherwise, and in the spirit of dialogue, Ambassador Ahmed, and countless classmates, concur. Not only do Muslims and Jews have a common heritage of universality, thoughtfulness, and humanity. They also are both seen as an “Other”, two minorities that share what one insightful woman in the class called “the commonality of tragedy.” For Jews, our tragedy is a series of expulsions from places we called home, reaching a nadir with the murder of six million Jews at the hands of Nazi Germany, a state whose ideology is seeped in scientific racism. For Muslims, the tragedy is forced displacement and sequestration at the hands of European colonialism and a fledgling Jewish settler state. Neither group has fully moved past these issues. The rise of anti-Semitism and harsh anti-Muslim sentiment in Europe before, during, and after the most recent Paris terror attacks is indicative that even in the West, the tide of progress is slow and steady.

Yet, on November 15, outside the Bataclan concert hall, where 89 people died at the hands of Islamic State terrorists, something transformative happened. Hassen Chagloumi, Imam of the Paris suburb of Drancy, and French Jewish author, Marek Halter, came together with members of their respective communities to assemble a memorial. They even broke out in an ecstatic rendition of the French national anthem, La Marseillase. For me, and for the world, this is a sign of hope. We can and must come together, in a spirit of tawhid, to make amends. We must repair our world, for my generation, and for future generations to come.

(Matthew Agar is a senior at American University studying International Relations with a focus on peace and conflict resolution in the Middle East and North Africa)