Brahminism in Britain

By Mowahid Hussain Shah

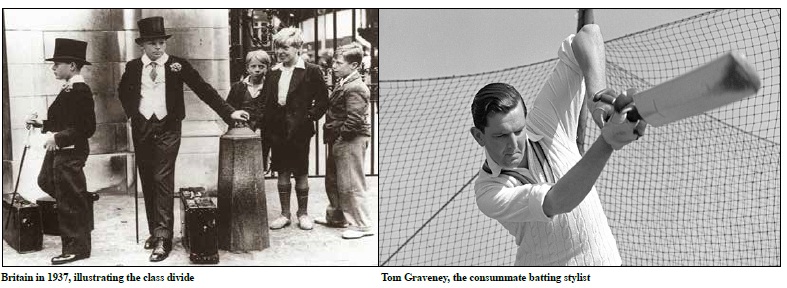

One reason that the British were able to gel in India was the easy transition from their own class-ridden culture to the caste-ridden Subcontinental society. As in India, Brahminism – an attitude of superiority and snobbery in the upper classes – was deeply embedded in Britain. Instructive is the biography, “Touched by Greatness” by Andrew Murtagh, of one of the classical English batsmen, Tom Graveney, who died November 3.

During the pioneering era of Pakistan cricket, Graveney was the batting mainstay of the MCC cricket team on its inaugural visit to Pakistan in 1951. He played in the two unofficial Test matches to ascertain whether Pakistan was ready for conferment of full-fledged Test status. He hit 109 in Lahore and, in the pivotal game in Karachi, he hit 123. This game Pakistan won, ensuring its entry in 1952 as the 7 th nation entitled to play Test match cricket.

The great Pakistani wicket keeper/batsman, Imtiaz Ahmed, who shall be 88 on January 5, told me that Graveney’s was the wicket they all wanted. Twelve years later, Graveney again toured Pakistan as part of Commonwealth XI, and hit two centuries in Lahore. During this tour, he persuaded his non-white South African teammate, Basil D’Oliveira, to join England county cricket – a portentous move, which was the first nail in the coffin of South African apartheid. Graveney toured Pakistan again in 1969 and hit his last Test century at Karachi. Graveney left an indelible imprint on Pakistan, including on Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif.

Graveney was an Egypt-based captain in the British Army in late 1940s. He left the Army to earn his living as a Gloucestershire County cricket player. In those days in England cricket, there was a division between upper-class amateurs called Gentlemen and working-class wage-earners who were called Players. There used to be a Gentlemen versus Players annual fixture, starting from the 19 th century, until 1962.

This was illustrative of the class divisions in mainstream society. For example, there were different dressing rooms demarcating the Players from the Gentlemen and, on away trips, the same team members used to stay in different hotels to differentiate the class gap.

A Player could not address a Gentleman team member by his first name. Graveney, a former British Army officer, was once admonished by his county captain and forced to apologize for the “egregious crime” of addressing a student batsman, David Sheppard, as “David.”

More significantly, it was occurring in a society with rich democratic traditions, where the Magna Carta charter was signed in 1215, curbing the arbitrary powers of the monarch. Revealing in all this was the subservience of the lower classes to passively submit to the superior writ of the upper hierarchy.

Britain’s upper classes, who viewed themselves as citadels of socio-cultural values, separated and distinguished themselves from the “inferior” lower classes through their attire, accent, manners, and schooling. The working and middle classes not only accepted this rigid division but, in effect, were participants in its enforcement. Instead of defiance, they contributed to a defense of the system.

It is that indoctrinated sense of powerlessness that sustains Brahminism in different forms elsewhere.