Pakistan Foreign Service: The Service that Was!

By Karamatullah K. Ghori

Toronto, Canada

The blue-ribbon, and once coveted, Pakistan Foreign Service is as old as Pakistan itself.

The new-born sovereign state of Pakistan needed to be represented, as such, in the world beyond Pakistan’s shores. But there were no professional diplomats to carry out that task.

Pakistan inherited its share of Muslim soldiers and officers serving in the British-Indian Army and other armed services to serve as the building blocks of its armed forces.

Likewise, Pakistan got its segment of Muslim officers from the hallowed Indian Civil Service (ICS) to serve as the bedrock of its successor, the Civil Service of Pakistan (CSP).

But the field of diplomacy was a terra incognita for the infant state. As such, spawning its diplomatic service was a job that had to be commenced from the scratch.

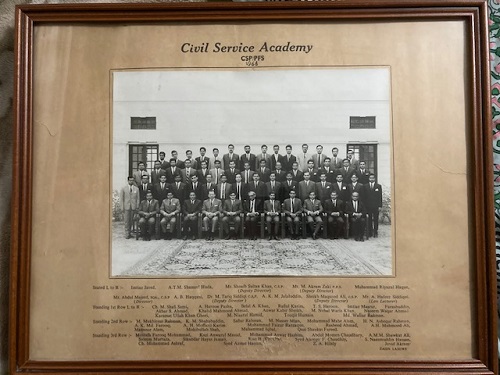

1966 batch of CSP and PFS under training at the Civil Service Academy, Lahore

Initially, officers to man the Foreign Office and serve in Pakistan’s Missions abroad were scrounged and recruited from both civil and military services. Some of these recruits—brilliant and highly competent in their own right—were, later, to rise to prominence. Agha Shahi, from the Indian Civil Service, later distinguished himself as a diplomat of international repute. He led the Foreign Office as its Secretary and also served as Foreign Minister. His is one of those few names of prominent Pakistani diplomats that may still resonate in the corridors of UN Headquarters, in New York.

Sultan Mohammad Khan, who had earlier served in the Indian army, was another. He was Foreign Secretary at the watershed period of the crisis in East Pakistan. In his capacity as head of the Foreign Office he played a crucial role in building bridges between China and the US that led to a furtive, highly secretive, visit of Henry Kissinger to Beijing to trigger a long overdue mending of fences between China and the US.

Regular recruitment to what came to be christened as the Foreign Service of Pakistan (PFS) didn’t start until 1949. That maiden batch of Foreign Service officers later shone bright to illuminate the world of diplomacy with their brilliance and radiance. Men like Niaz Naek and Iqbal A. Akhund distinguished themselves, and the country they so competently represented in world capital, are stars on the firmament of Pakistan’s global horizon.

Not surprisingly, training of officers recruited to PFS was almost entirely on the pattern left behind as its legacy by the departed colonial power.

PFS officers were sent abroad, to British and American universities and other institutions, for training. There was little of local content in their training. The end result of it was that man to man our PFS officers could hold their own against the best from those countries that had diplomatic service firmly implanted in rich traditions going back to centuries. But Pakistan was not a colonial state, nor were its moorings in Western culture. It was an ideological state founded on the vision of its founding fathers whose mission was to transform the lives of their people on the tenets of Islamic progressivism.

Our first generation PFS officers were, every inch, replicas of the English ‘Sahibs.’ But that aping of the colonial model didn’t blend with, nor projected, the founding principles of Pakistan.

Ironically, it was under the military dictatorship of Field Marshal Ayub Khan that the practice of grooming our PFS officers in Western institutions was stopped.

So, in the context of history, the indigenous baptism of PFS took place with the onset of the decade of 1960s. This scribe has the honor of having joined the coveted PFS in 1966, a few years after its attempted donning of Pakistani colors.

However, as I discovered soon after joining the Civil Service Academy in Lahore—the place where officers of CSP and PFS were put through their paces and initiation—the thrust of training imparted there to the new recruits was still anchored in making them ‘Brown Sahibs.’

Yes, there were regular courses in the history of Pakistan Freedom Movement. Yes, there were regular lectures on Islamic history. Yes, we were also immersed in courses that focused on Pakistan’s social and economic challenges and problems. Yes, we were taught the fundamentals of laws that governed Pakistan.

But there was a heavy sheen, over our training, of the British colonial tradition of making their civil servants a breed of ‘superior’ men, aloof and detached from the mainstream of the people they were supposed to serve. We were trained into the mannerism and traits of the departed colonial officers. Horse riding, at the crack of dawn, was a compulsory part of our training. I used to scratch my head why should horse riding be part of upbringing of an officer in a day and age when motorized transportation had long replaced the 19 th century perquisite of a ‘Sahib’ riding through his realm of administration on a horseback?

But that was the way it was. Mess nights, we had to be garbed either in a tuxedo or a black Sherwani. In a nutshell, the emphasis in our training was on turning out Brown ‘Sahibs’ to carry on the legacy of their departed White precursors in the job. In my book, training at the civil Service Academy was attuned on lines that could well describe the place as a ‘factory’ to churn out not servants of the people but their masters.

Of course, local flavor was injected by taking us on a journey across Pakistan on rails. A special train, complete with our mess and kitchen staff and a dining room on the wheels, was pressed into service take us to all parts of the then West Pakistan. It was a travel of luxury, with all the homely comforts, from Karachi to Landi Kotal. But it was worth the effort as it gave a thorough insight into rural and urban Pakistan.

We were sent on two tours of East Pakistan. The first was spent, entirely, at the world-famous Rural Development Academy, Comilla. That place was a lesson worth every minute spent in its precincts. The Academy was a brain-child of Dr Akhtar Hameed Khan, a scion of ICS, who had shirked that hallowed service to devote himself, for life, to the upliftment of rural folks and peasants of that part of Bengal that later became part of the Eastern half of Pakistan. Akhtar Hameed Khan had been honored with a Megasaesai Award, from the Philippines, which was known as the Nobel Prize of the East.

Our second tour of East Pakistan took us to every nook and cranny of that part of neglected Pakistan. It was capped off with a week-long attachment at the Chittagong Military Garrison where we were given training in how to handle a variety of arms, ranging from revolver to machine gun. It was a rewarding training, in every sense of the term, despite compulsory physical exercises and long marches through hilly terrains, with a ten- kilo bag on our backs.

In short, our training was well-rounded in almost all aspects of the life ahead of us. At the end of the year-long training at the Civil Service Academy—and going through what was to be the Final Passing Out Exams, conducted by the same Public Service Commission of Pakistan that had initially selected us—we were ready, as PFS probationers, to join the Foreign Office, in Islamabad, for another several months of hands-on training into the arcane art of international diplomacy.

(To be continued)

The writer is a retired Pakistani ambassador who served the country as a career diplomat for 36 long years. He can be reached at K_K_ghori@hotmail.com