In modern language, Al Gazzali’s position can be stated as follows: The laws of nature are not deterministic. Cause and effect are not necessary consequences of each other; they exist “side by side”. The outcome of a natural phenomenon is a moment of God’s grace

Why Did the Scientific Revolution Not Take Place in the Islamic World? - 4

By Professor Nazeer Ahmed

Concord, CA

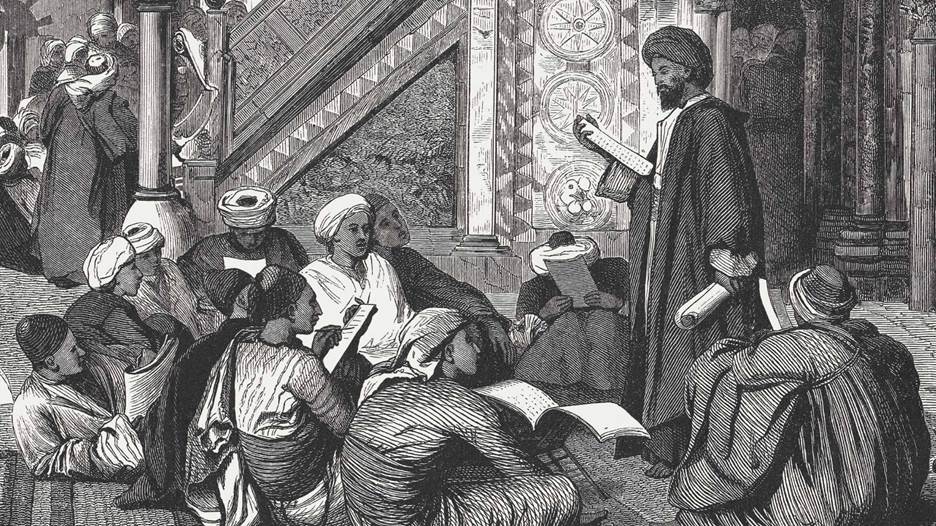

The intellectual storms created by the Mu’tazalite and anti-Mu’tazalite movements continued to rage long after the eighth century. The Islamic world had come face to face with Greek rationalism and was trying to reconcile its belief system with reason. Was there an interface between reason and faith? If there was one, where was it? The major intellectual figures of the Islamic Golden Age grappled with this question and advanced their own views and their own theories.

Among the most influential of the usuli ulema who tried a reconciliation of reason with faith was the Shafi’ scholar Abul Hasan al Ash’ari (d 936). To maintain the transcendence of God and preserve His power over all decisions, Al Ash’ari advanced the thesis that time was discrete and was built up of small increments (atoms). At each increment of time, the Will of God intervenes and determines the outcome of an event. Thus, in the Asharite cosmology, a natural law which appears to follow the logic of cause and effect gets broken up into an infinite series of occasions for the intervention of the Will of God. Those who accepted the philosophy of al Ash’ari were called Asharites. The Asharite ideas found wide acceptance in the Islamic world and influenced some of the major thinkers of Islamic history including Al Gazzali and Allama Iqbal.

Al Ash’ari’s thesis was a major step towards a reconciliation of faith and reason. Al Ash’ari rejected the Mu’tazalite position that the Qur’an was “created”. He explained that the divine attributes of seeing, hearing and action are different from those of human beings and must not be understood in anthropological terms.

However, in advancing his own “atomistic” theory of time, Al Ash’ari left himself open to a critique from the philosophers and scientists. What is time? Is it linear? Is it discrete? Is it warped? Is it even “real”? The limits of reason are the limits of human understanding of time. The Qur’an offers profound insights into the nature of time to guide humankind in its quest for the Truth. The passage of time, absolute time, perceived time, time as a moment, time as a day and as a mirage are all clarified in different contexts in the Qur’an. The definition of a natural phenomenon must therefore state, a priori, its assumptions of time within which the phenomenon are defined. Otherwise, observations, theories and deductions that are derived in one timeframe become speculative when applied to a different timeframe. Al Ash’ari won the debate against the Mu’tazalites of the day. However, his assumptions are insufficient to accommodate modern theories of quantum physics. The search for a satisfactory definition of the interface between reason and faith is perpetual and must continue.

The Approach of Ibn Sina and the Scientists

Ibn Sina was one of the most celebrated scientists of the Islamic Golden Age. His approach to the question of cause and effect in nature was fundamentally different from that al Ash’ari. To preserve the overarching authority of Divine Will in nature, Al Ash’ari conceived of time as moving in discrete, small increments (atoms). Ibn Sina, on the other hand, tackled the more fundamental issues of “change” and the “agent of change”. He constructed a hierarchy of causers of change and distinguished between the “necessary” and the “contingent”. God is “necessary”, he maintained, whereas the created world is “contingent”. In the cosmology of Ibn Sina, the metaphysical structures of necessity and contingency were different. The necessary is “the source of its own being without borrowed existence. It is what always exists”. By contrast, “the contingent being is ‘false in itself’ and ‘true due to something else other than itself… It is actualized by an external cause other than itself.” Thus, the theories of Ibn Sina stay close to the guidance provided by the Qur’an. However, his esoteric arguments of the “necessary” and the “contingent” were too complex for the layman and his works remained unknown except among the scholars and the elite.

Al Gazzali’s Tahafut al Falasafa (Repudiation of the Philosophers)

Abu Hamid al-Gazzali (d 1111) was one of the most influential theologians, jurists and skeptical philosophers in Islamic history. Born into a Persian-Arab family in Tus in Northeastern Iran, Al-Gazzali received his early training in Qur’an, fiqh and tasawwuf in the local religious schools and then studied under a well-known scholar, al-Juwayni of Nishapur. The erudition, brilliance and intellectual acuity of the young Al-Gazzali attracted the attention of Nizam ul Mulk, the grand vizier of the reigning Seljuks, who conferred upon him the title of “hujjaatul Islam” (evidence of Islam) and appointed him a professor at the Nizamiya College in Baghdad. His lectures on jurisprudence and tasawwuf attracted a wide following and his fame spread far and wide.

After teaching at the College for four years, Al Gazzali went through a profound internal crisis. Outward ritualistic observances of religion and esoteric philosophical discourses brought him no inner peace. He quit his prestigious professorship and embarked on a journey to Damascus, Jerusalem and onto Mecca and Madina for hajj. His introspections during this period brought him the conviction that true faith resided in the heart, and it was only through a cleansing of the heart and constant remembrance of God that man ascends to Divine presence. Al Gazzali returned to Nishapur (1098) where he founded and taught at a Zawiya, a college structured on Sufi teachings. In 1106 he returned to the Nizamiya College and continued to teach there until his death.

Al Gazzali lived in a period of great political turmoil. The Islamic world was divided between the Fatimids in Cairo and the Abbasids in Baghdad. The Sunni Seljuqs backed the Abbasids and were engaged in a military struggle with the Shia Buyids of Iraq for control of Baghdad. The Crusaders, taking advantage of the Fatimid-Abbasid rivalries, were successful in capturing Jerusalem in 1099. The assassins, a band of disgruntled Fatimids, were active throughout the Islamic world, causing havoc with their targeted killings of Sunni leadership. Nizamul ul Mulk himself fell to an assassin’s dagger in 1092.

On the intellectual plane, the turbulence generated by the injection of Greek philosophy continued to roil theological debates. It had been four hundred years since the Mu’tazalite movement had first enjoyed and then lost the patronage of the Abbasid courts in Baghdad. Through these centuries, the intellectual genius of Muslim scholars had struggled to accommodate the challenge of Greek ideas. The work of Al Ash’ari (d 936) had brought a degree of calm to this intellectual landscape but the undercurrents of a perceived disharmony between faith and reason persisted.

Al Gazzali injected himself headlong into the Fatimid-Sunni and philosophy-theology debates. His dialectic reflects the political and intellectual turmoil of the age. He argued eloquently against the esoteric doctrines of the Fatimids as well as the deductive approach of the philosophers. In his treatise Tahaffuz al Falasafa (Repudiation of the Philosophers), he contended that the metaphysical arguments of the philosophers did not meet the test of reason. Basing his powerful dialectic on the earlier works of al Ash’ari, Al Gazzali argued that there was no cause and effect in nature, and that all natural events happened by the Will of God.

“The connection between what is habitually believed to be a cause and what is habitually believed to be an effect is not necessary… For any two things, it is not necessary that the existence or the nonexistence of the one follows necessarily from the existence or the nonexistence of the other. Their connection is due to the taqdir of God, who creates them side by side, not to its being necessary by itself.”

Al Gazzali supported his argument by offering the combustion of cotton as an example:

“We say that the efficient cause of the combustion through the creation of blackness in the cotton and through causing the separation of its parts and turning it into coal or ashes is God—either through the mediation of the angels or without mediation”.

In modern language, Al Gazzali’s position can be stated as follows: The laws of nature are not deterministic. Cause and effect are not necessary consequences of each other; they exist “side by side”. The outcome of a natural phenomenon is a moment of God’s grace.

(The author is Director, World Organization for Resource Development and Education, Washington, DC; Director, American Institute of Islamic History and Culture, CA; Member, State Knowledge Commission, Bangalore; and Chairman, Delixus Group)