Book & Author

Razia Fasih Ahmad: Breaking Links

By Dr Ahmed S. Khan

Chicago, IL

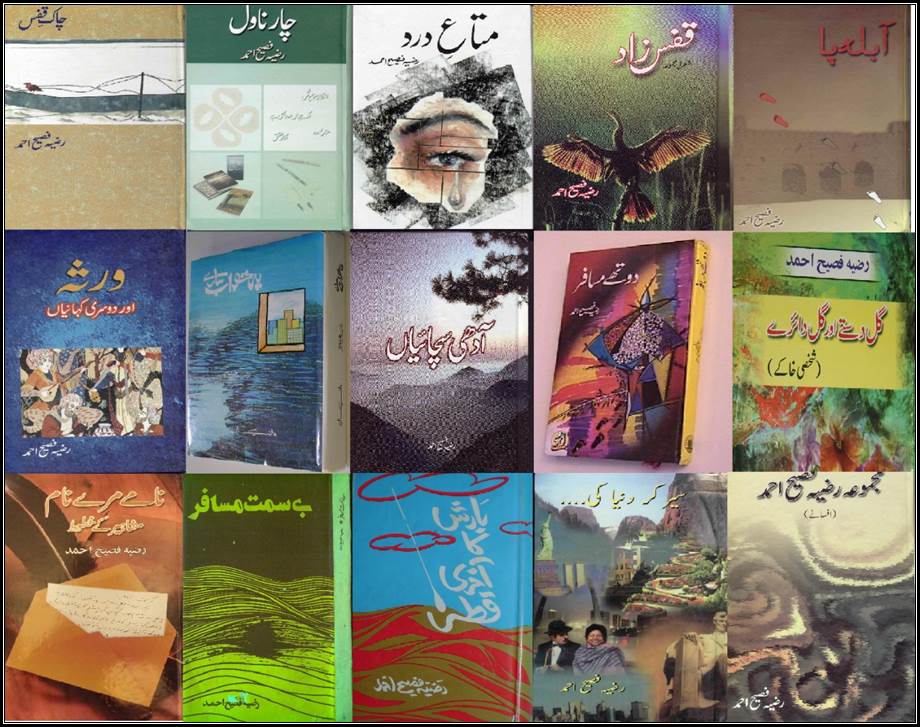

Razia Fasih Ahmad is a living legend of Urdu fiction. She presently resides in Elgin, a suburb of Chicago. She moved to the United States in the mid-1980s. During the last seven decades she has produced a vast array of intellectual outputs : ten novels, two novelettes, five collections of short stories, a collection of short stories in English, two travelogues, a collection of humorous essays, a collection of plays, and a plethora of other short articles. She started her literary career with short fiction stories. Her popular novel titles include Seemeen (1964), Abla-Pa (1964), Intizar-e-Mosam-e-Gul (1965), Ek Jahan Aur Bhi Hai (1966), Mata-e-Dard (1969), Tapti Chhaun (1969), Azar-e-Ishq (1971), Atash Kada (1983), Sadiyon Ki Zanjeer (1986), Yeh Khwab Sare (1992), and Aadhi Sacchayan ( 2008) . Her most recent novel is Zakh'm-e-Tanhai (2007). It is based on the life of the Bronte sisters of England: Charlotte, Emily, and Ann Branwell are authors of Jane Eyre, Wuthering Heights, and many other literary works. She has also authored in English, a collection of funny stories about everyday life in America, titled Americans Are Punny People: Recognizing Humor in Everyday Situations (2015). Her short stories in English have been broadcast on the BBC World Service and published in the US. Her poetry collections include Chak-e-Qafas and Qafas Zad. She is currently compiling another poetry collection. Her novel Abla-pah won the Adamji Prize for Literature in 1964. She also won the Writer’s Guild Prize for best short story for Aankh ka Kanta, and later won Ahmad Nadeem Qasimi Award for her novel Zakhm-e-Thanhai, and the Urdu Board Award for her literary accomplishments. She was given a Lifetime Achievement Award for Urdu Literature (2011) by Iqra Magazine, Karachi.

Breaking Links is the English translation of Razia Fasih Ahmad’s Urdu novel Sadiyoon Ki Zanjeer (Chained Centuries) based on the chain of events that unfolded as a result of the political clash between West and East Pakistan. (Fifty years ago, the tragedy of 1971 was an outcome of total leadership failure; people of the two wings never divorced each other). She did the translation herself. It is perhaps the first book that focuses on the human suffering of conflict: how families got affected and how politics affected human relationships. The author has put in considerable effort to get the facts and details of events right. She traveled to Bangladesh and talked to people of different viewpoints and gathered facts related to the 1971 tragedy. She has presented a true picture of the violence and bloodshed: the horrors of war. In Breaking Links, Razia Fasih Ahmad has very eloquently juxtaposed history with romance.

It is ironic that her voluminous literary contributions have not been officially acknowledged in the form of a national award by the government of Pakistan. I sincerely hope that leaders of Pakistan will soon bestow on her the recognition she deserves, and that has been long overdue!

May Allah SWT bless Mohtarma Razia Fasih Ahmad with good health and a long life, so that she will continue to serve Urdu literature with unique distinction! Ameen.

__________________________________________

What a cruel thing is war: to separate and destroy families and friends, and mar the purest joys and happiness God has granted us in this world; to fill our hearts with hatred instead of love for our neighbors, and to devastate the fair face of this beautiful world.

-General Robert E. Lee (letter to his wife, 1864)

War is indeed a cruel thing. Politicians and generals, who consider winning war as easy as a “slam dunk,” declare war; and in the process ordinary people and families, who never seem to know much about the intricacies of politics and war, get torn apart.

The breakup of Pakistan and the emergence of Bangladesh in 1971 is a sad saga of South Asian politics. Many eminent scholars and historians have addressed the key questions for the Dacca debacle: Could the disintegration of Pakistan have been avoided by leadership and moderation on the part of three parties (General Yahya, Mujib and Bhutto) involved in the final dialogue? Was Indian involvement surely for humanitarian consideration or did India exploit an opportunity to destroy its archrival Pakistan? How did the superpowers of the day support their key constituents? But writers and academics have failed to address the magnitude of human suffering and human toll of the 1971 tragedy.

There are many similarities between the American civil war and Pakistan’s civil war of 1971. In the American civil war, there was the North versus South divide. In 1861 the young and struggling nation of the United States was divided into two opposing political, cultural, and economic ideologies. The North with its industries, financial institutions, universities, rail transportation, and newly arrived skilled European workers was a forward-looking region. In contrast, the South with its agriculture-based economy, aristocratic mindset, and institution of slavery was a backward-looking region. The Southern aristocracy, rooted in the past, promoted a slave-based society and was ready to die to defend its lifestyle. The cost of the Civil War was enormous in terms of human lives and destruction of resources. But in the end wisdom prevailed, the forces of truth won, and the country remained united. Many books have been written about history as well as human suffering.

In 1971, Pakistan was also a young country that was hijacked by a military dictatorship. The military generals and politicians failed to live by democratic principles and to promote social equity and justice. The East Pakistanis perceived West Pakistan to be rich and denying them the fair share of national resources for their development and growth. The West Pakistanis failed to understand the genuine demands of the East Pakistanis. The Pakistani leadership lacked wisdom and vision. There was a complete leadership failure in all domains. The situation was exploited by Pakistan’s archrival India.

Indian propaganda machine was effective in sowing the seeds of hatred and mistrust; it created a perception among East Pakistanis that the revenues from their cash crop jute was being used for the economic growth of West Pakistan. It was an internal conflict, but the resolution of the conflict was shaped by the politics of the Cold War. In contrast to the Soviet Union’s full support of India during the 1971 Indo-Pak war, Pakistan’s main “friends,” China and the US, failed to offer any meaningful assistance to resolve the conflict. The end result was the disintegration of Pakistan; East Pakistan broke away and emerged as the new nation of Bangladesh. In contrast to the American civil war, for Pakistan’s civil war of 1971, unfortunately, writers, scholars and academics wrote mainly focusing on the politics and history, and they failed to shed light on the human suffering of the war in an unbiased manner.

Breaking Links is the English translation of Razia Fasih Ahmad’s Urdu novel Sadiyoon Ki Zanjeer (Chained Centuries) based on the chain of events that unfolded as a result of the political clash between West and East Pakistan. She did the translation herself. It is perhaps the first book that focuses on the human suffering of conflict: how families got affected and how politics affected human relationships.

The author has put in considerable effort to get the facts and details of events right. She traveled to Bangladesh and talked to people of different viewpoints and gathered facts related to the 1971 tragedy. She has presented a true picture of the violence, rape, murder, and bloodshed: the horrors of war.

In Breaking Links, Razia Fasih Ahmad has very eloquently juxtaposed history with romance. The plot is like a complex mosaic of events and characters. The author has used beautiful metaphors to describe the economic and geographical disparities of her characters.

The novel consists of two parts. The first part deals with West Pakistan’s present and past, and the concept of national integration, and tells a story of romance and marriage. The second part presents the sequence of the changing political climate that led to the disintegration of political and personal relationships. The author tells a story of two main characters - Zari, belonging to the West, and Shams, to East Pakistan. Shams and Zari, who work together on tourism projects, fall in love, and end up marrying each other hoping that their union will promote national integration, but their marriage gets deeply affected by the political violence that grabs the country and results in its dismemberment.

The author begins the novel with an introduction to the Turkish soldier, Qasim Khan, who centuries ago came to India as a soldier with Bakhtiar Khilji. The author traces the lives of the descendants of Qasim until the 1970s. Qasim first lands in the region of Bengal (former East Pakistan, presently Bangladesh) where he marries a local girl, Mukul; Shams is her descendent. Qasim yearns for his homeland and decides to go back to Turkey. In his journey back home, he passes through the areas which presently makeup the northern areas of Pakistan, where he marries Suzan; Zari is the descendent of Suzan. The locals out of respect start calling him Miyan Sahib. Many generations later the descendants of Qasim and his two wives, belonging to West Pakistan and East Pakistan, cross their paths again.

The author has used simple but powerful language to portray the agony and trauma of events. Her description and narrative of events, spoken by her characters, are rich in detail, and she has succeeded in giving the reader a true sense of the message she wants to convey. For example, through one of the main characters, Shams, she presents the perceptions of the East Pakistani people: ‘Turning away from the truth doesn’t solve the problem. We East Pakistanis think that people from West Pakistan do not try to understand our culture and our customs. Instead, we are ridiculed, though we were, and still are, more educated than them. People have now started saying that just as India has not willingly accepted the partition, the West Pakistanis haven’t accepted the majority of Bengalis in Pakistan. Otherwise, they would not have hesitated in declaring Bangla as the second language along with Urdu. That’s not all. Other provinces have their names, for example, there’s Punjab, Sindh, Frontier, and Balochistan. But our province has no name. When we try to give it a name, the government sees it as if we are creating a separate state.’….’So you have started the Bangla Nationalist Movement. Is it going to be a real danger?’… if certain things are not taken care of it might. I know there is much poverty here as in the East wing. But when visitors come to West Pakistan, they are given tours of the neat and clean suburbs of Karachi and Islamabad. They are shown big factories in Lahore and Faisalabad. This is a bad strategy. They get the wrong impression of West Pakistan being rich and prosperous while East Pakistan is getting poorer day by day.”

Through the eyes of another character the author vividly presents the image of the surrender of the Pakistan army: “Yes, I have seen the tragic ceremony… At first General Niazi signed the papers then he took out the revolver from the pocket and gave it to General Arora. As he turned away, someone from among the crowd hurled his shoe at him. Local people lifted General Arora over their shoulders. The Bengali public threw garlands around the necks of the bearded Sikh soldiers and hugged them. The caps of Gurkha soldiers were decorated with flowers, and petals of marigold flowers were scattered over their heads.”

What led to the fall of Dacca? The author presents the answer through the dialogue of another character: “The Pakistan government has been hiding things from the public … they were hoping that conditions might change. Not only the public, but the soldiers, intellectuals, politicians, and military officers, even the commander of the Eastern Command General Niazi, were kept in the dark. They were hoping that help was just about to arrive from friends, meaning China and the United States, even when that hope was gone, they kept it secret to gain more time for the representative of Pakistan to seek a mandate from the United Nations. They also kept the people of West Pakistan under the illusion that if the East could bear the brunt of war for a few more days, the Pakistan army would capture Kashmir.”

Razia Fasih Ahmad has also presented a deeply touching account of how war affects and victimizes human beings, especially women. When Zari, the main character of the novel, after giving birth to a baby boy a day before the fall of Dacca, finds out that her baby has died, she expresses her sorrow and agony: “Why do such things happen to us women? Why do women have to pay the heaviest price of wars and revolutions? ... Because we are not taught to hit back, that’s why. We are taught to take the beating…I say if all the women of the world decide not to give birth to a child unless all deadly weapons were destroyed, and peace restored, wouldn’t men come to their senses? But who’s going to teach them such wisdom, and make them realize their strength?”

In the Finale of Breaking Links, Zari, in response to her husband's invitation of reconciliation, reflects on her dilemma: “Yes, she wanted to be with him too. But she was from Pakistan, Sham would be alien in Pakistan, while she would be an alien in Bangladesh and they would both be aliens in any other country, although they were both descendants of the same Miyan Sahib who had come to India with Bakhtiar Khilji centuries ago.”

Breaking Links , published by Oxford University Press, is a powerful novel that deals with the human aspects of the 1971 tragedy. Embedded in the plot of the novel are the historical accounts of the misperceptions and realities of peoples about each other, India-Pakistan hostilities, and cold war politics which eventually led to the disintegration of Pakistan in 1971. The book is a must read for all those who want to learn from history, and those who want to promote peace, justice, and social equity. It offers wisdom for policy makers: the implication is that war is not the answer, war is the highest form of human ego. The use of military force to solve global problems arising from differing viewpoints, economic interests, and ideologies is as futile as drinking lemonade to tame the inflated ego.

Author’s Interview

Q: When and how did you decide to write Sadyon Ki Zanjeer?

A: I visited East Pakistan during 1965 and again in 1967 to receive the Adamji Prize for my novel Abla Pa. These experiences were very different. In 1967 I could feel the rift between East and West Pakistan as the Bengalis were extremely reluctant to speak with West Pakistani writers in Urdu. They made it clear that if we did not speak the Bangla language they would prefer to talk to us in English. My experience in Army cantonments was that in every gathering there were separate groups of West and East Pakistani officers and families who never shared their thoughts, grievances, and misunderstandings. This attitude on every level resulted in misgivings and animosity. After the 1971 war and my husband’s retirement from the Pakistan Army, I met many Biharis in Karachi who had fled from East Pakistan during the turmoil. Their stories were different from what we had heard in the West Wing. After getting this insight and not finding any significant writing on the subject at that time, I decided to write this novel.

Q: What led you to translate the novel into English?

A: One lecturer in India translated it but the scholars did not think it up to the mark. It was not accepted by the publishers and so I decided to translate it myself. Oxford University Press (OUP) wanted it abridged so I cut it short, and the OUP got it edited.

Q: You traveled to Bangladesh to do research on your book. Based on your interaction with people of different viewpoints, what actions could have prevented the fall of Dacca?

A: I went to Bangladesh in 1985 to conduct research for this novel. I met many scholars, Mukti Bahini leaders, editors of newspapers and people from different walks of life. Most of them told me that Sheikh Mujeeb wanted autonomy and not a separate state. The mismanagement by the Pakistan government, Army action in March 1971, and growing influence of Bengali student leaders led to the war and fall of Dacca. Fairness in dealings between the two wings and political dialogue could have prevented the breakup.

Q: Who is your favorite character in Breaking Links and why?

A: Omar is my favorite character. He is very perceptive and wise like a sage and guru. He has a unique personality.

Q. What are the lessons to be learnt from the fall of Dacca?

A: The government should be fair and considerate and treat everybody equally. Should a conflict arise, it should be dealt with fairly and through political dialogue. Most importantly, there should be a just cause to win a war.

(Dr Ahmed S. Khan - dr.a.s.khan@ieee.org - is a Fulbright Specialist Scholar)