In many ways, she was a

symbol of the generation

of middle-class females

who grew up in the sixties

A Sister Departs

By Dr Asif Javed

Williamsport, PA

She was older than him. Number four in her siblings, she was the third daughter in a row. Their parents would have much preferred a son. Imagine the disappointment they must have felt. But there she was -- another daughter.

He only has a vague memory of her school years. He remembers her college years a little bit. That was back in the sixties. Their hometown did not have a women’s college then. And so, she had to go to Gujrat and stay in the college hostel. Neither of her older sisters had been given this opportunity by their Aligarh-educated father and a semi-literate mother. On the contrary, all the brothers were encouraged, and expected, to go to college. Decades later, she said to him once that ours is a man’s society. Only now does he perceive the pain hidden in that remark. She did well in college. A cup she had won in a debating competition somewhere remined visible in their home for years. Always confident beyond her years, she once went on a college tour to Karachi and brought back pictures of Sukkur Barrage and Ayub Bridge. The little brother, then a primary school student in their native village, was fascinated by what he saw in those pictures and heard of Karachi from her.

In middle school, he was required to deliver a speech in Bazme-Adab. While he was terrified of facing an audience, she came to his rescue, and wrote a short piece on Mahmood of Ghazna with the following verse in it:

Mein Muslim hoon azal say bot shikan hoon

Mera shewa nahin hey bot faroshi

He delivered the lines using the time-honored rote method and made her proud of little brother.

Two years is all she was allowed in college. She was married to a lawyer, twelve years older than her. The bewildered little brother watched her leave their house as a bride and kept wondering why she was crying. She was to spend the rest of her life in the provincial city of Jhang.

To call Jhang provincial is an understatement. It is as backward as they come. In a family of feudal mindset and obsolete traditions, she must have found the adjustment terribly difficult. An unexpected welcome break came when her husband decided to proceed to UK for LLM. She joined him a few months later along with their infant daughter. Hard to believe now but she flew to UK on Ariana Afghan Airline from Karachi via Kabul.

The time in the UK was a mixed blessing. As her husband struggled with his law studies, she, always full of energy and ever so resourceful, found a part time job to support her family. Two decades later, her son, who resides in London, showed her brother, a modest two-room apartment in Tooting Broadway, South London where his parents had lived back in the early 70s. Two children were added to the family in London. Going to movies over the weekends was her entertainment. She saw several movies of Dilip Kumar who was her idol.

On their return to Pakistan in 1972, the old routine was resumed in Jhang. Her husband, more interested in politics than law practice, had ups and downs in his political career. Once when he was Vice Chairman of District Council

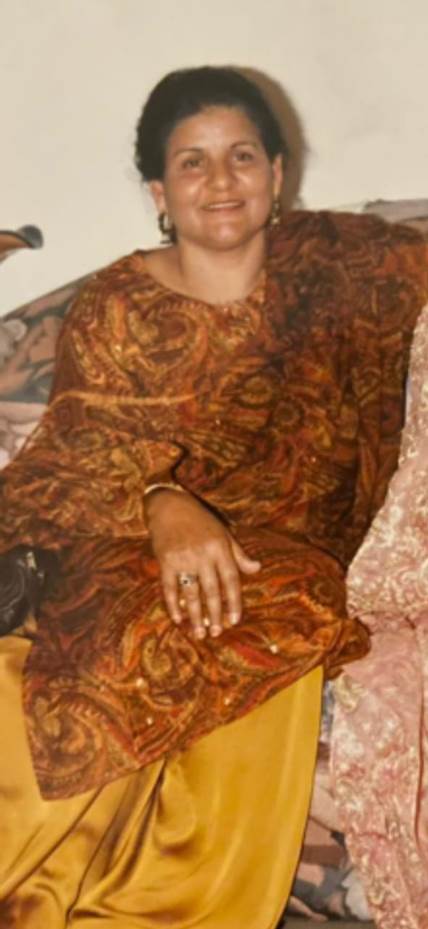

Sister Ismat Mumtaz with

husband and children

Jhang, they visited Lahore, and stayed at Flatties Hotel where he, then a medical student, visited them. He was thrilled to see his big sister staying in what to him looked like a grand hotel.

In many ways, she was a symbol of the generation of middle-class females who grew up in the sixties. Those were the days when Wahid Murad was popular among the college girls, while Dilip Kumar was the undisputed king of filmdom on both sides of the border. Rafi, Lata, Talat and Mukesh were in their prime and Binaca Geet Mala presented by Amin Siyani from Radio Ceylon had a huge following. Zeb-un-Nisa, Batool, Hoor, Ismat were popular magazines. He vaguely remembers Wahida Nasim and Surraya Jabin's short stories being discussed by his sisters. Razia Butt, M. Aslam, Ibn-e-Safi and Nasim Hijazi's novels were in demand. A collection of Manto's short stories was first seen by him in her bedroom, understandably, hidden under a pillow.

When the family returned from the UK, she brought back a tape recorder, then a novelty. She used to play her favorite song by the Welsh singer, Mary Hopkins:

Once upon a time there was a tavern, where we used to raise a glass or two.

Remember how we laughed away the hour, think of all the great things we will do.

Those were the days my friend, we thought they will never end.

We will sing and dance forever and a day, we will live the life we choose.

We will fight and never lose, for we were young and sure to have our way.

Then the busy years went rushing by us, we lost our starry notions on the way.

Just tonight I stood before the tavern, nothing seemed the way it used to be.

In the glass I saw a strange reflection, was that lonely woman really me.

Now that he thinks about this, her life was a reflection of her favorite song: She fought a few 'battles' too. A valiant one was against her ultra conservative in-laws. She withstood immense pressure to get her daughters married outside their clan. This was an unheard of departure from tradition. But her perseverance, in which her late husband was a reluctant supporter, won the day. Both her daughters remain happily married.

The last years were difficult. She was lonely, her husband having preceded her in death by almost two decades. None of her four children lived in Jhang. For several years, she had become very religious, had been studying Arabic to better understand the Qur’an, and had become pretty good at it recently, one of her daughters reports. Years ago, when the brother was visiting Pakistan, she accompanied him to Feroz Sons in Lahore, recommended and bought a collection of Hadith for him.

A couple of years ago, she sent a package to him in USA. The contents had a pleasant surprise for him. The package contained more than a dozen letters that he had written to her in Pakistan. That was back in the’80s, when he was training in the UK. The big sister's letters would arrive every few weeks and sustained him through a period of loneliness and stress. But while he saved none of hers to him, she had saved all of his. Three decades later, she made sure to carefully return them to him. After her passing, the distraught brother is struggling to figure out the depth of his sister's affection for him. It may take a while for him to figure this out. But this made him think of Mirza Sahiban's story.

Legend has it that Mirza, a master user of bow, was unable to use it to defend himself from Sahiban's brothers who were intent on killing them. It is said that Sahiban threw away his bow since she did not want him to hurt her brothers who had surrounded them. She loved Mirza dearly. But her love for her brothers exceeded that she had for him. The irate brothers of Sahiban killed both lovers. Incidentally, Sahiban was from Khiva, a village near Jhang.

The sister was multi-talented. One that she would display, when in mood, was her uncanny skill of parody. She would produce hilarious parody of a local politician's wife and sometime of Tahira Syed and Noor Jahan's singing. A good storyteller, she would often regale him with stories from movies and novels. To this day, he remembers how she narrated the story of Naila, Razia Butt's novel, later made into a popular movie.

She used to have a fairly wide circle of friends. But over the years it had dwindled due to poor health that had limited her travels. Still, she maintained close ties with some. One of her closest friends from school days recalls with fondness their teenage years: Being neighbors, they would spend hours together, exchange magazines, and would make plans for the future. Deep inside, they were probably aware that their options were limited. While her friend got married into an affluent family and had a stable traditional life of a homemaker, sister's was more of a struggle at times. Easily the most talented among her siblings, she was not given the opportunity that a person of her talent and ambition deserved. Although, she did fulfill her usual obligations, expected of a middle-class housewife and mother, at times, her frustration at 'what might have been' would show up. He recalls a time when she scolded her younger son who was not preparing hard enough for CSS. "Only if I had the opportunity," she said in frustration.

For their extended family, she missed no opportunity to help. She was often the first to arrive and last to leave in family medical emergencies although she lived the farthest and mostly travelled on public transport. Self-sacrifice was in her genes perhaps. She was devoted to her children. When the time came to reciprocate, all four of them kept a bedside vigil for two weeks while she remained hospitalized. The end came on August 4th on a hot and humid Lahore afternoon when she quietly slipped into the night. Making fuss was never her style.

Now that she is gone, her grief-stricken brother, sitting in a faraway land, has started to realize why Mary Hopkins' song remained his sister's favorite all those years. In several ways, her life had symbolized its lyrics: Long gone were the days laughed away in laughter with friends; the starry notions were lost on the way too; she did not really live the life that she would have chosen; and as the busy years went rushing by her, she found herself a lonely woman for whom nothing seemed the way she had imagined back in the swinging sixties. Such was the life of Ismat Mumtaz. RIP dear sister.

Nahin Labne Lal Gowache

Too Mittee Na Phirole Jogya

(The writer is a physician in Williamsport, PA and may be reached at asifjaved@comcast.net)