Rudyard Kipling, it is said, contributed more phrases to the English language than anyone else, except Shakespeare; he was known to, and admired by, men in high places (his poem If was the favorite poem of Woodrow Wilson, while King George V was a personal friend); he visited six continents and lived in four. But, through all that, Kipling did not forget and remained in love with Lahore

The Englishman Who Loved Lahore

By Dr Asif Javed

Williamsport, PA

The other day, I saw The Jungle Book with my son. As the movie ended, I realized that it was based on Kipling’s famous story, written in India, about a boy who finds himself in Seonee Jungle (in Indian state of Madhya Pradesh) and survives having befriended animals. It then dawned upon me that more than a century after The Jungle Book was written, Kipling’s work is still popular. His writings have passed one test of a writer’s greatness - the test of time.

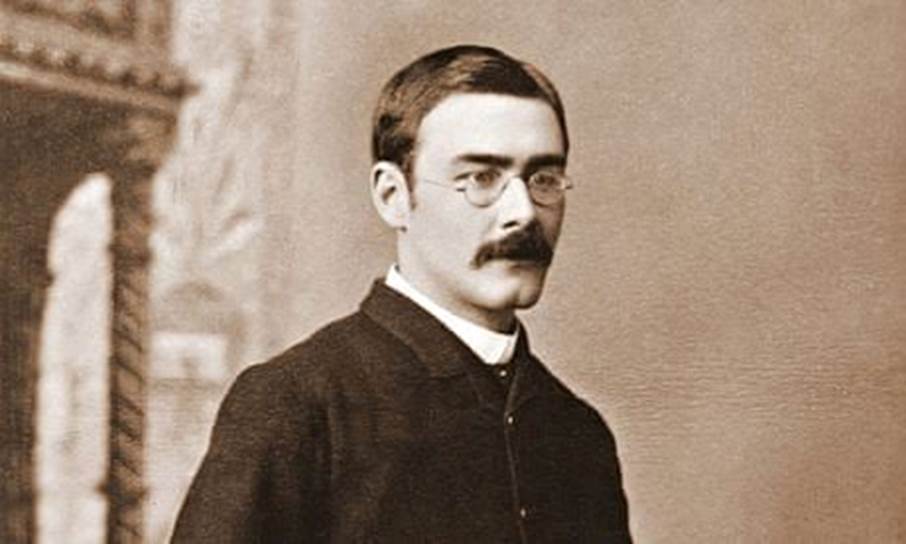

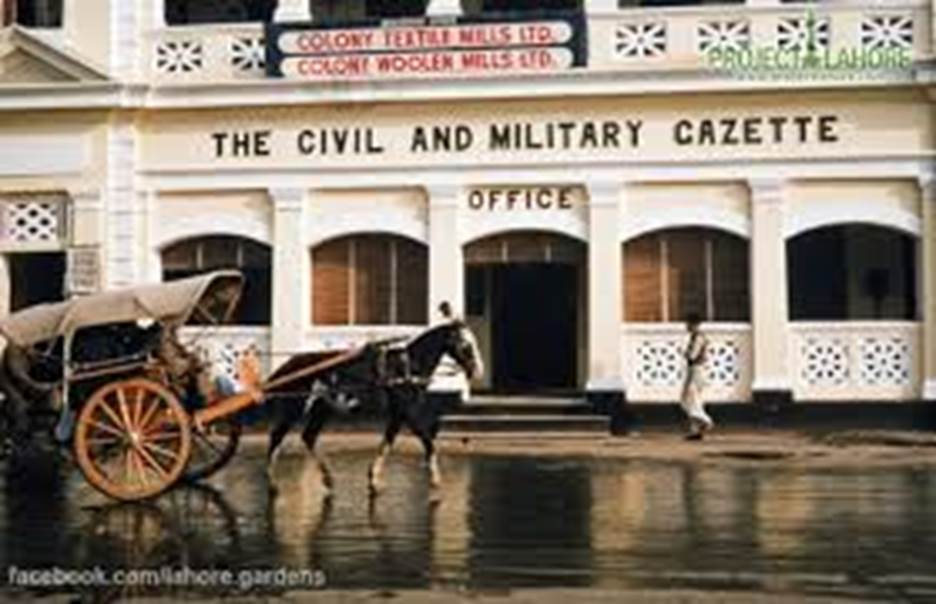

Born to English parents in India, Rudyard Kipling (RK) learnt Hisdustani—presumably Urdu—as a child. Although the city of his birth was Bombay, the one that he really came to admire was our own: Lahore. Having spent eleven years in a boarding school in England, seventeen years old RK returned to India and became the assistant editor of the Civil &Military Gazette in Lahore. It did not take him long to fall in love with the former capital of Akbar the Great and Ranjeet Singh. RK’s fondness for Lahore is often obvious in his writings: he exercised at the Racecourse, played tennis in the Lawrence Gardens, danced in Montgomery Hall (old Gymkhana), had dinner in the Punjab Club, and became a member of the Freemasons Society. There were moonlit picnics at Shalimar Gardens. Even visits to Lahore’s infamous Red Light Area where the future Nobel Laureate contracted a venereal disease.

RK used to wander in the bazaars and alleys of old Lahore that he once described as ‘that prodigious brick honeycomb’. The Grand Trunk Road is described as ‘that broad smiling river of life’ and Delhi Gate, ‘a compound of all evil savors that a walled city can breed in a day and a night…combining the foul smell of badly-trimmed kerosene lamps, and the stench of native tobacco, baked brick, and dried earth’. While at Lahore, he wrote articles on Mohurrum Festival and Festival of Lamps in the Shalimar Gardens.

In 1887, RK was transferred to Pioneer in Allahabad, a sister publication of C &M Gazette but missed Lahore terribly. As fate would have it, he was recalled to Lahore for a few months in 1888. Mrs Hill, a friend of RK, noted how he did ‘love those wild men of the north, whom he called his ‘own folk’; after living among the frog-like easterners of Allahabad, he was happy to be back among the ‘savage, boastful, arrogant, hot-headed men’ of the Punjab.

RK spent about five years at Lahore. Having left in 1887, he returned to his beloved city only once. But like Manto who once quipped about Bombay (I am carrying my Bombay with me), RK seemed to have done the same with Lahore and for his second novel, he chose the title, The Naulakha. These days, Naulakha is a low middle class locality in Lahore. But in RK’s time, it may have been different. It is quite possible that RK, who was single at the time, lived with his parents in or near Naulakha. One of the pavilions in Lahore Fort is also known as Naulakha. While it is not clear whether RK had the former or later in mind, his fondness for Lahore is obvious. The novel was not received well. But RK was not quite done with Lahore. Years later, after he had married an American and had come to live in the state of Vermont in USA, RK built a house in Brattleboro, VT that he also named, Naulakha.

Edward Robinson, the editor of C&M Gazette, and RK’s boss, reports this of RK’s interest in Lahore:

Deeply interested in the queer and works of the people of the land. He liked to hunt and rummage among them, especially in Lahore, ‘that wonderful, dirty, mysterious ant hill’, a city he knew ‘blind fold’ and which he loved to wander through ‘like Haroon Al-Rashid in search of strange things’….he found ‘heat and smells of oil and spices, and puffs of temple incense, and sweat, and darkness, and dirt and cruelty, and above all, things wonderful and fascinating innumerable’.

Another thing that connects RK with Lahore is his famous story, The Man Who Would Be King. Some believe that this story was based, at least partly, on real events. Danial Gilmour, RK’s biographer, reports that RK had come across a mysterious character who asked him to convey a package to another stranger at a train station at some distance. Perhaps, RK created the characters of Daniel Dravot and Peachy Carnahan based on that encounter. RK may also have heard of an American, Josiah Harlan, an adventurer, who had managed to create a kingdom, on paper, in Northern Afghanistan, having signed a written agreement with Prince Mohammad Refee of Ghor on October 16, 1839. Harlan had spent years in India and Afghanistan, having worked for East India Company, Raja Ranjeet Singh in Punjab and Amir Dost Mohammad Khan in Kabul. Harlan and RK’s paths did not cross since the American mercenary had left India in 1839. But his exploits had become the stuff of legends and RK may have used his writer’s imagination to create the story. The contract mentioned above still exists in Chester County Museum, PA.

Fact or fiction, The Man Who Would Be King remains one of KP’s most famous stories, having been immortalized by John Huston in his classic movie of 1975. In the movie, Sean Connery played the role of Dravout who along with his companion Carnahan deserts the British Indian Army and carves out a kingdom for himself. Dravout is perceived as God by the simple Kafiristan folks, until the truth is revealed when Dravout is killed. Meanwhile, Carnahan manages to escape and, after a lot of hardships, meets up with a journalist in a newspaper office. The story ends at The Mall in Lahore, where a disoriented Carnahan, suffering from a sun stroke, is recognized by the journalist from the night before, and is sent to an asylum where he dies. It is ironic that Bhawani Junction, which was filmed in Lahore in the 1950s (when Ava Gardner created a sensation) was not about Lahore while The Man who would be King, with Lahore background, was actually made in Morocco.

RK wrote his masterpiece Kim, widely considered his best Indian work, in 1901, twelve years after leaving India. He spent eight years writing it. Those who have read it—I have not—are convinced that the writer had to be in love with India. The novel opens with the main character sitting atop Zamzamagun that still sits on the Mall, opposite Lahore Museum. It was in Kim that RK used the famous phrase “the great game”. It was a reference to the struggle for supremacy between Czarist Russia and the British in Central Asia. This phrase, in fact, was first used by a Captain Connolly back in 1842 but RK was the one who publicized it.

‘And his nostalgia persisted,’ writes RK’s biographer David Gilmour, ‘so that he used to yearn to revisit Pindi racecourse or the elephant lines at Mian Mir. But although his plans to return to India never materialized, his imagination remained there, encouraging him to write some of his most serious stories about Anglo-India and the imperial mission.’

RK did have a dark side. At a rail station in England, RK considering himself a celebrity, jumped the queue. Asked to go back in line, RK said to the station master, ‘Don’t you know who I am?’ The station master’s response must have startled him: ‘I know who you are, Mr Rudyard

On his next visit to Lahore, this scribe intends to stand on The Mall, on the former site of C&M Gazette, and bow his head in gratitude to the memory of the Englishman who loved Lahore and carried his Naulakha with him to Vermont and beyond

Bloody Kipling, and you can bloody well take your place in the queue like everybody else.’ Jumping the queue is a trait that RK might have sub-consciously acquired in India. It is also on record that infamous General Dyer, who had been condemned by the House of Commons for his barbaric massacre at Jalianwala Bagh, received a monetary contribution by RK. He may have loved Lahore, but RK was an imperialist and English jingoist at heart.

RK left India in 1889. A few years later, a young Winston Churchill served in India, as a soldier and a war correspondent. WC’s book, The Malakand Field Force was written in 1897. It was published in The Pioneer where RK had worked earlier. WC passed through Lahore, on his way to NWFP and visited the Civil & Military Gazette office in Lahore since Pioneer and Civil & Military Gazette were sister publications. RK and WC’s paths did not cross in India. But one is intrigued by the coincidence that both the future Nobel Laureates had a Lahore connection.

The Zamzama gun and Lahore museum, or “House of Wonders”, both of which feature in Kim - Photograph: John Mcconnico /AP

Majeed Sheikh, whose father was the last editor of C & M Gazette, and who has written numerous superb articles about Lahore’s glorious past, writes of a chair that reportedly had been used both by RK and WC at the C & M Gazette office. The newspaper ceased publication in 1963. But what became of that chair? Does anyone really care? Perhaps the publicity seeking CM of Punjab, once he has finished his mega projects, can be asked to have at least a plaque placed on The Mall on the former site of that newspaper. This will be a well-deserved tribute to RK. RK, it is said, contributed more phrases to the English language than anyone else, except Shakespeare; he was known to, and admired by, men in high places (his poem If was the favorite poem of Woodrow Wilson, while King George V was a personal friend); he visited six continents and lived in four. But, through all that, RK did not forget and remained in love with Lahore.

On his next visit to Lahore, this scribe intends to stand on The Mall, on the former site of C&M Gazette, and bow his head in gratitude to the memory of the Englishman who loved Lahore and carried his Naulakha with him to Vermont and beyond.

(The writer is a physician in Williamsport, PA and may be reached at asifjaved@comcast.net )

Back to Pakistanlink Homepage