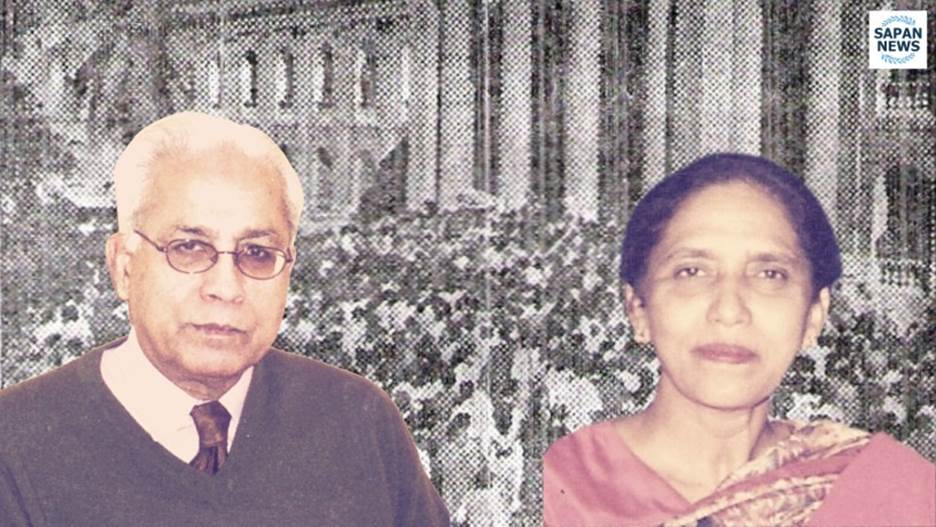

The legacy of a decades-old connection between social worker Shahida Haroon (1937-2023) and economist Eric Rahim (1928-2023) endures through the ongoing struggle for student rights, economic justice and democracy in Pakistan

A Social Worker, an Economist, and the Legacy of Pakistan’s Student Movement of the 1950s

By Beena Sarwar

Boston, MA

It was while trying to reach Eric Rahim in Glasgow this week to inform him of my aunt Shahida Haroon’s passing in Karachi that I learnt he too was no more.

A respected journalist and economist, Uncle Eric as I called him, had passed away peacefully at home on 2 May 2023, aged 94. He was a mentor to my father Dr M. Sarwar (1929-2009), and Shahida, who departed this earth on 25 June, at 87.

Shahida Haroon Saad

Shahida did her Master’s in economics from Karachi University in 1958, a subject she didn’t enjoy or do well in. When she went to Punjab University for a second Master’s in social work, encouraged by her brothers Akhtar, 11 years older, and Sarwar, eight years older, Akhtar asked his friend Eric Rahim to look after her. It was Eric, then a columnist at The Pakistan Times, who met Shahida at the train station after her overnight journey.

Born in British India in Montgomery (later Sahiwal) in 1928, located in then Lyallpur district (now Faisalabad), he was one of 10 children . Their father Tarey Rahim Khan was a landowner and mother Rose Fateh Massih a teacher before marriage.

Shahida was also one of 10 children, of whom two boys and five girls made it past childhood. The family lived in Allahabad in Uttar Pradesh, India and were untouched by the violence of the 1947 Partition. Visiting the ‘new country’ Pakistan a year later, Sarwar joined Dow Medical College in Karachi.

Shahida and their parents, younger sisters and Akhtar followed in 1949, going by train to Bombay, then to Karachi on a now discontinued steamship service.

A former student activist at Allahabad University, Akhtar got a job as sports reporter at Dawn, where Eric was a columnist. My father and his friends at Dow, “bonding over cadavers” as he told me, launched the Democratic Students Federation (DSF), Pakistan’s first nation-wide student movement, in 1949.

No party politics

Like many of their friends, Eric and Akhtar were members of the Communist Party of Pakistan (CPP). My father supported it but diligently kept party politics out of student union activities. He discouraged comrades from bringing party literature onto campuses and overtly CPP-affiliated student union candidates. Doing otherwise, he explained, would be divisive for the student unity he was trying to build.

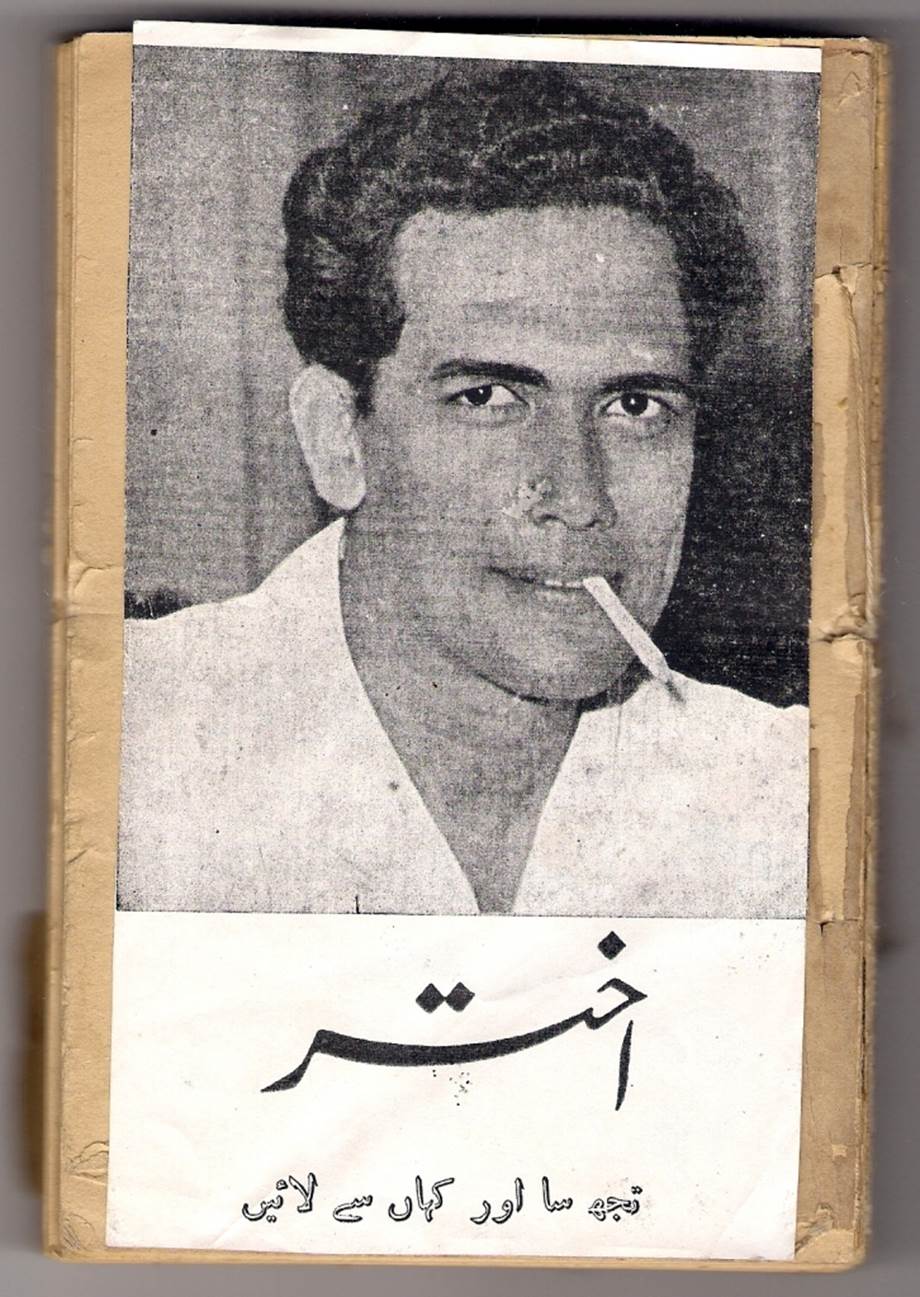

Akhtar book cover, essays edited by Ibne Insha. Photo: Beena Sarwar family archives

Akhtar and Sarwar encouraged their sisters and nieces to get higher education and supported their right to work after marriage. But while my father’s role in the student movement was well known and acknowledged publicly, I had never heard about the role of girl students.

I learnt of it after Sarwar’s demise in 2009 when I began researching the student movement in earnest, driven by an urgency to document it while some of its stalwarts were still alive.

I learnt that when Shahida joined Government Women’s College, Karachi, Sarwar encouraged her to run for the college student union. She and her younger sister Rashida even did theatre “in front of so many people” – somehow allowed by their conservative parents.

They and other girls in the family participated in the Demands Day processions of January 1953, when students took out massive rallies calling for rights like more equitable fee structures, better laboratory, library and hostel facilities, a purpose-built university for Karachi, and security of employment.

I’m glad I was able to record some of that in my documentary Aur Niklen.ge Ushhaq ke Qafle (‘There will be More Caravans of Passion’), a title drawn from a poem by Faiz Ahmed Faiz at the suggestion of another student-movement stalwart, the late Saleem Asmi , former editor Dawn.

It’s not just the larger DSF movement but also these histories that our schools or textbooks ignore.

The poet and editor of Pakistan Times Faiz Ahmed Faiz was already behind bars in the famous Rawalpindi Conspiracy Case of 1951 when there was “a general round-up in West Pakistan in the wake of the triumph of the United Front in East Pakistan elections of 1954 and Pakistan government’s decision to sign military pacts with the United States,” as Eric Rahim wrote later .

‘ Government hospitality’

Sarwar was among the first to be picked up. The police turned up at his house in PIB Colony one morning and hauled him off, sleepy and still in his pajamas. Eric was among the CPP unit arrested in June 1954 under the Security of Pakistan Act 1952 , “accused of spying for India and the Soviet Union”, writes Joanna Rahim . “They were not charged but held without trial.”

Journalists Akhtar, Shakoor and SM Naseem – student editor and publisher of the DSF paper Student Herald – also “enjoyed government hospitality in Karachi jail in 1954” as Uncle Eric wrote to me in 2012, a typically whimsical understatement.

He particularly appreciated the “constant supply of books” from my grandfather Abdul Haleem, “without which the inmates would have found life even more difficult”, he wrote in a note about Sarwar in 2020.

“Where did he get these books from? I remember reading all the volumes of Churchill’s war memoirs – you had plenty of time, of course. That was supplied by him, and many others. I have fond memories of him. I am grateful for his contribution to my education. I may also recall the way that the Jail censorship worked. If a book was published in Moscow, that was forbidden, as was a book with the name of Marx or Lenin on the cover page. But a book, for example, with the title of dialectical materialism and published in London was okay.”

Throughout their incarceration, Akhtar and Sarwar’s friend Haroon Saad, editor of the Urdu daily Imroze, visited their parents every day, bringing roasted peanuts and engaging in political ‘ gup shup’ (conversations), recalls my aunt Rashida.

When I got permission to film inside Karachi Central Jail for my documentary, the superintendent mentioned that he had been a member of DSF in Hyderabad and “did a lot of wall chalking”. This was probably in the 1980s. General Zia ul Haq’s military regime (1977-1988) banned student unions in 1984. No subsequent government has revived them despite promising to do so.

Film director Sharjil Baloch and I never imagined that our modest film about DSF, supported by donations from friends, family, and my father’s comrades, would contribute towards reviving the progressive student movement in Pakistan later.

Similarly, the 1950s activists probably never expected that Student Herald would be such a valuable resource over 50 years later. It informed my research and documentary, which contributed to the launch of a new digital Students Herald in April 2020, with the blessings of SM Naseem, Dr Haroon Ahmed, and Saleem Asmi.

Before leaving for University College London in 1958, Uncle Eric went to Punjab University and sought Shahida out, insisting on taking her out for a goodbye lunch. In London, he was “greatly astonished” to run into his old comrade and former jailmate Dr Ghalib . A reminder that, back then, even close comrades were in the dark about each other’s whereabouts.

Eric’s plans to return to Lahore as a senior commentator for the Pakistan Times were stymied by the imposition of martial law in October that year. He never returned except for occasional visits.

In December 1958, when Shahida returned to Karachi for the winter vacations, Akhtar was in hospital, critically ill with pneumonia. He died within days , aged 31. My grandmother never recovered from Akhtar’s loss. Shahida too bore a similar grief when her eldest daughter Samina Saad died after contracting Covid-19 in February 2021.

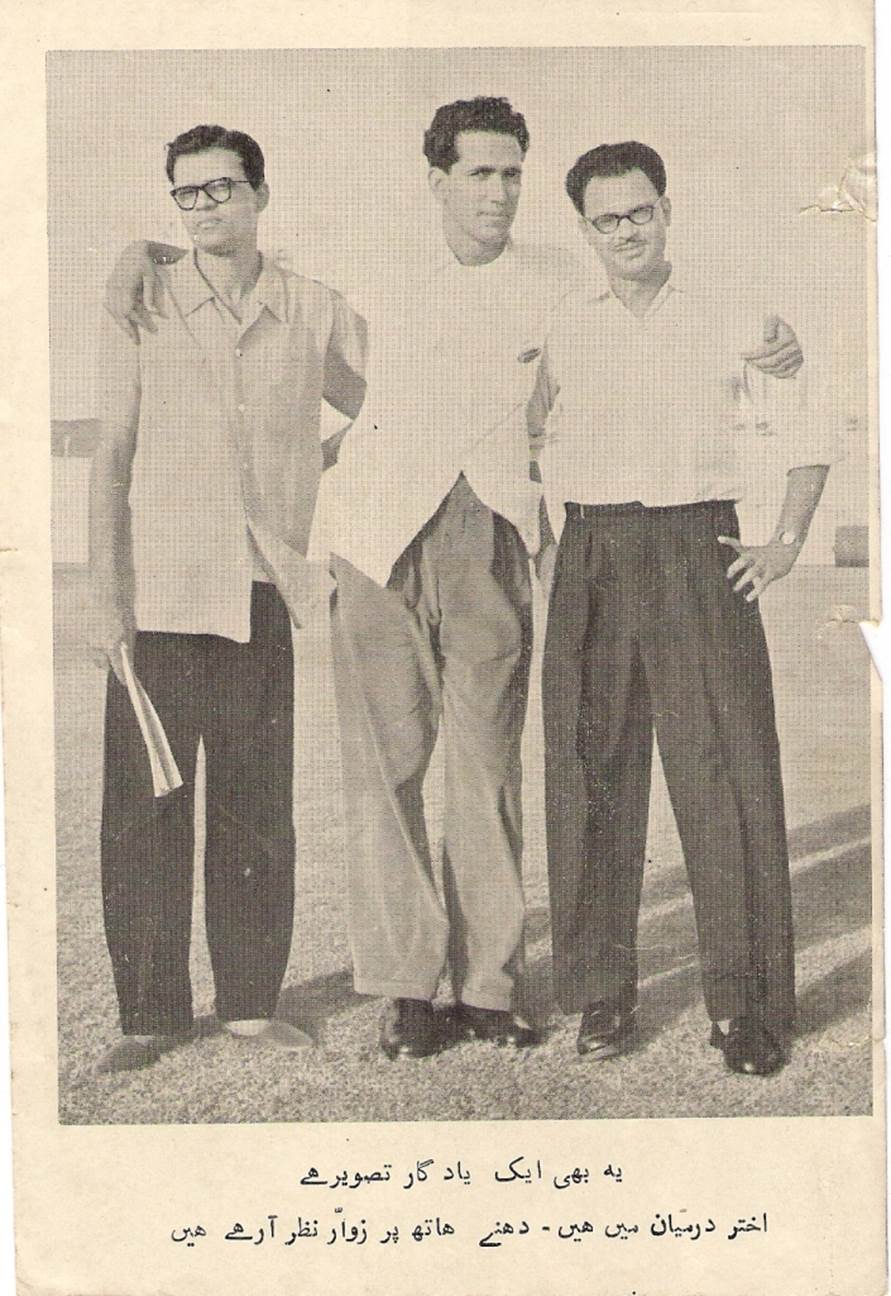

Besides Eric who was in London, Akhtar had another close friend who mourned his passing – Zawwar Hasan , my mother’s brother, who was in the US on a fellowship at the time.

Akhtar (center), Zawwar (right) and a friend - Photo: Beena Sarwar family archive

It was Akhtar and Zawwar’s friendship that connected my parents in 1962. That was the year Shahida married Akhtar’s journalist friend Haroon Saad in Lahore. She and my mother became good friends. After Shahid retired and moved to Karachi with her son and his family, she played a crucial role in helping Zakia organize the Spelt, the teacher training organization she started.

Eric and I interacted mostly on email, occasionally telephone. Once when I called him, he had classical music playing loudly in the background and a salmon baking in the oven. I learnt later that Aunty Edith had passed away.

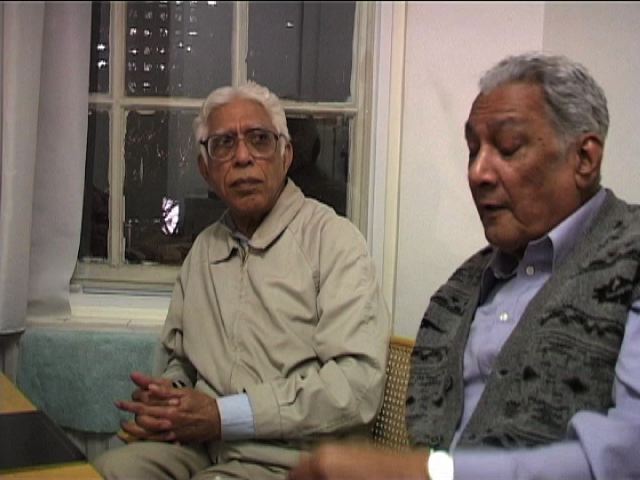

They had met when Uncle Eric was completing his PhD in economics, and she had come to London from Vienna to learn English. In 1963, Eric was offered a lectureship at the newly created University of Strathclyde, Glasgow, and Ghalib offered to drive him there.

Along the way, Ghalib mentioned wanting to study biochemistry. Eric, surprised, realized that this would require a full-time course. He was planning to buy a flat on mortgage and get married in a few months. “My would-be wife knew Ghalib quite well. I suggested that he stay with us and pursue his study,” he writes in his tribute to Ghalib .

So Ghalib lived with them during his two-year MSc course at Strathclyde University.c

Dr M. Sarwar and Dr Ghalib, London, 2001 - Photo: Beena Sarwar

Solas and Marx

Around the year 2000, Dr Ghalib asked Eric to set up a charity to promote education with money that he had saved for that purpose. The Solas Educational Trust was born, with Eric serving as convenor until the end. He was proud of the work Solas did, helping several non-profit community schools in Chitral, keeping Dr Ghalib’s original £100,000 intact in investments.

Eric was keen for his work to be shared in Pakistan. In November 2017, he sent me a compilation of his non-academic essays in the form of a short book: “For internet use only, of course, I hope you like the collection. If you do, please circulate it among your friends.”

I edited and formatted it, inserted a table of contents, converted it to a PDF and posted it to Scribd: ‘ Was Marx a 100% Materialist?’ and Other Essays From a Marxian Perspective .

In March 2020, Uncle Eric emailed me his manuscript on Karl Marx’s early life, A Promethean Vision (Praxis Press and Marx Memorial Library, London), wanting it to be published in Pakistan. Bilal Zahoor, who runs Folio Books in Lahore, happily obliged. The Folio edition was well received in Pakistan.

Eric Rahim

His mobility was “very limited” and he had balance issues, he wrote in October 2022. “Otherwise, I am active writing, just published a paper with the title Piero Sraffa: Doing ‘History in Reverse’.” He attached the essay , published by the Sage Journal of Interdisciplinary Economics.

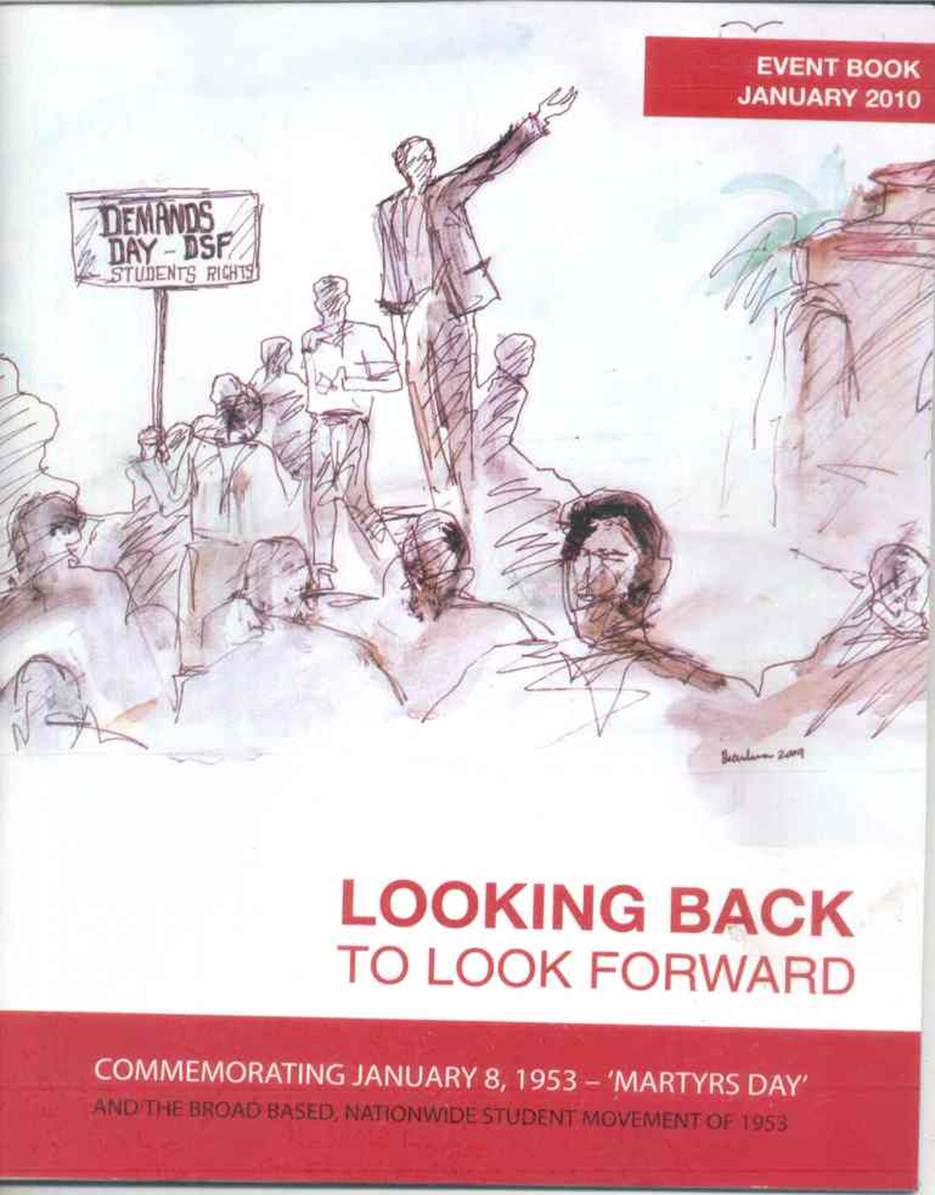

When planning to commemorate the student movement in Karachi, January 2010, I’d consult Uncle Eric on how to go about the event. When there was some confusion about why we were doing this, he wrote: “This is an important question – perhaps, THE question: why do we ‘commemorate now the events of 1953’.”

“Sarwar was a good man and a good friend, a lovable person, a significant personality” – all “reasons good enough to celebrate his life”, he wrote in an email on 1 December 2009.

“But more than that, we celebrate his life because of his role in the student movement of the early 1950s – a movement of which progressive people can still feel proud of. For me, Sarwar’s passing away and the reactions and responses it evoked provided a great opportunity to celebrate that movement. But most importantly, we look back not to revel in nostalgia, WE LOOK BACK TO LOOK FORWARD. For this we need to consider the circumstances that led to the creation and development of that movement, causes of its decline and to some extent we need to understand what has happened (good as well as bad) during the intervening period. Now, this is a tall order. But we can make a start.”

Basically, said Eric, we need to do something that “would advance our thinking on how to move forward.”

‘Looking Back to Look Forward’ became the title of the event commemorating Sarwar and the 1950s’ student movement.

Cover of event book, ‘Looking Back to Look Forward’, January 2010

The veteran student activists got a standing ovation from the full house at the Karachi Arts Council ’s open-air auditorium ( video clips here ).

In that vein, the purpose of this piece is not to revel in nostalgia, but to shine a light on the lives and aspirations of those who have gone before us and to take their work forward.

(Beena Sarwar is a multimedia journalist and documentary filmmaker who focuses on human rights, gender, media and peace. Co-founder and curator of Southasia Peace Action Network , and founder editor of Sapan News , this article revives her column, ‘Personal Political’. Email beena@sapannews.com)

Read more about DSF at the Dr Sarwar website . See also Shahida Haroon’s 2014 essay (Urdu) YadoN ke Dareechey (Flood of Memories). A Sapan News syndicated feature