Rashid Latif: The Master’s Voice – III

By Siraj Khan

Boston, MA

After two articles last year, a part 3 on The Master seemed inevitable. However, there was so much to write about, and the stream of words seemed to be overflowing in different directions. In the end, I did manage to contain it to fit into the desired word limit.

So, we continue our journey with the present attempting to embrace the past. My guest, Rashid Latif, who is former Federal Secretary Information & Broadcasting, CEO EMI Pakistan LTD and Shalimar Recording & Broadcasting Co. LTD., is ready. And so, here we go. - Siraj Khan

Siraj Khan: You have had a long and illustrious career in sound and music. Please share with our readers one single experience which has been so profound that you can recall it clearly and readily, even today.

Rashid Latif: In mid-1956, returning from the UK after my technical training in sound recording (besides all the other mechanical and electrical types of machinery that were used in producing and replaying 78 RPM shellac records), I was sent to Lahore to transfer some movie soundtracks on to the Company’s magnetic tape recorder. My recording career’s first transfer was “Ulfat ki nai manzil ko chala” sung by Iqbal Bano for the movie Qatil.

Having been trained in high-quality recordings, I found that recording terribly poor (editing joints were noisy) and felt that it was not suitable for producing gramophone records. That created quite a rumpus. The film studio staff and the producer of the movie all gathered around to convince me that the recording was good enough for reproduction. I phoned the Head Office in Karachi and was instructed not to ruffle feathers, as both Iqbal Bano and the music director, Master Inayat Husain, were already recognized names in the music industry. Unlike film joints, splices on magnetic tapes are inaudible to human ears, so I removed those blips on the tape recording and nobody noticed those defects.

The next task was to sign a contract with Iqbal Bano. She told me to see her after 1 pm as she gets up late. I showed up at the given address as directed and to my surprise, it turned out to be a “kothaa” in the red-light district of Lahore called Shahi Mohalla or Heera Mandi. I must confess that, at that time, my knowledge of the kothaa was limited to the Mujra scenes in Indian movies, as I had never been to a real one. That turned out to be my first and last encounter with a kothaa. The crumpled flower petals and wilted garlands were strewn all over the white sheets on the floor beside a harmonium and a pair of tablas as the remnants of, what must have been, a colorful story the previous night. After making me wait for a while, she eventually came out to sign what was to be the first ever artiste’s contract of my career.

In its glory days, EMI International used to control all its overseas branches, excluding the British network. The total strength of its employees hovered around 40,000.

SK: You have often mentioned Talat Mahmood in our exchanges. Does this go in the realm of hero worship or is it something different? May I request you to please share and amplify this for our readers?

RL: I first heard Talat’s recording in 1941 from the loudspeaker of a cinema house that was about 1 km from our house. Meerut at that time was a very quiet town with only three cars. The cinema used to play records for half an hour before the show to attract cine-goers. I was certainly enthralled by his voice right after listening to his song, “ Sub din ek samaan naheen thaa” the first time. I can distinctly remember listening to his songs, even while sitting in our garden. Talat’s voice was clearly different from other male singers who I had heard.

After moving to Karachi, the only picture frame hanging on my bedroom wall had his photo, cut out from some magazine. In Karachi, I met Talat’s elder brother, Kamal Mahmood, and his sister among other relatives. In Dhaka, I met Talat’s eldest brother, Hayat Mahmood. So, I met many members of my idol’s family before meeting the idol himself in 1961 when he visited Pakistan for the first time. I recorded four titles, including Faiz’s “Khuda woh waqt na laa-aiy ke soagwaar ho tu”. In this record, I was very pleased to preserve the talents of two of my idols, Talat and Faiz, on one disc. Both were very soft-spoken thorough gentlemen. The music was arranged and conducted by one of Pakistan’s top composers, Sohail Rana. During recording, I noticed that, unlike other singers, Talat was a very soft crooner. His voice was hardly audible beyond a distance of three feet. We owe it to the highly sensitive microphones that carried his melodious voice to millions of his fans all over the world. I arranged Talat’s several live concerts, each of which attracted so many fans, including Mehdi Hasan, Ahmad Rushdie and SB John, that we had to seek police help to control the milling crowds.

Talat was the first Indian playback singer to perform outside India. It was a foregone conclusion that the moment we met, we were best of friends. A little later when I went to Mumbai to visit some of my relatives, he insisted that I should stay at his apartment. Out of hundreds of artistes, I was never a house guest of any to avoid a conflict of interest. But how could I refuse Talat’s invitation? For him, I broke my self-imposed law and stayed at his apartment. Every time I visited Mumbai, I used to call on him. When he was on his deathbed, I was so busy shifting to Canada that I could not take a trip to India. In his death, I lost my idol and elder brother. Just like a child, I wept for hours.

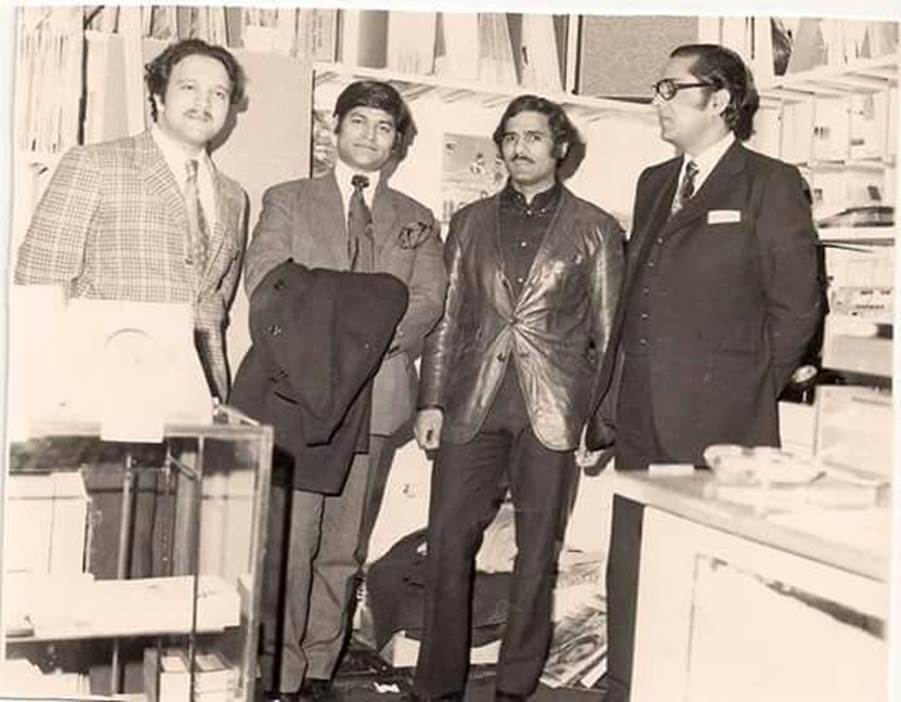

From R-L: Rashid Latif, Mushtaq Hashmi, maestro Sohail Rana and Dr Amjad Parvez

SK: Talking about Talat Mahmood’s Pakistani recordings under Sohail Rana’s baton, I wanted to cover him before we move on. Sohail Rana is one of the most talented music directors to have emerged from Pakistan. Your association with him has been long and engaging, and as fate would have it, both of you migrated to Canada and now live in the same city too. I believe you have even travelled to India together. Would you call it an all-weather friendship?”

RL: When we met first, he was either completing his graduation or was a fresh graduate. He had good command over the accordion, so I invited him to the EMI factory. He told me that when he wanted to meet me at the Karachi factory, the security guards at the main gate did not allow him. I explained to him that because records were manufactured in a plant, having large and dangerous machinery, it was a protected area. I gave him my business card to show that to the guards whenever he wanted to visit us. Obviously, he had no difficulty entering the premises when he paid his second visit. Unlike Lahore musicians, who had, barring a few, hardly any formal education, Sohail was a graduate. His etiquette and manners reflected his well-groomed cultural background and that struck a good note. The all-weather friendship has lasted more than 60 years, despite Sohail being an extremely religious person, also indulging in Peeri–Mureedi, while I completed my diamond jubilee of being an agnostic last Eid (21st April 2023).

Pakistan has produced many top-notch composers, but not a single all-rounder like Sohail Rana. In addition to being a composer-arranger-conductor and lyricist, he is a competent administrator. I did not find anyone else in Pakistan who could handle all these sectors with competence and efficiency. He is the only Pakistani composer who visited EMI’s huge complex in suburban London and met many of its executives, besides visiting Mumbai, along with Mansoor Bukhari (then CEO of EMI Pakistan Ltd) and me. We also called on Lata Mangeshkar, Asha Bhosle, Naushad and many others. That was March 1984.

SK: Perhaps this may be a good opportunity to steer you in a different direction but still relevant – the inner dynamics of EMI of those days – something I have always wondered about.

RL: In its glory days, EMI International used to control all its overseas branches, excluding the British network. The total strength of its employees hovered around 40,000. The London suburb of Hayes, where its head office and a network of companies and factories were located, had the name of its main Western line railway station as “Hayes & Harlington, the Home of His Master’s Voice.”

The company was originally called His Master’s Voice. In 1931, it acquired Columbia Recording Co., and changed its name to Gramophone Co. Ltd. All its subsidiaries were then renamed Gramophone Co. Ltd. During WWII, the company made substantial contributions to Britain’s war efforts. In fact, its invention of radar saved London from German bombarding aircraft, as it could trace the German aircraft long before they reached British airspace.

The company had expanded from records to defense equipment, household appliances, hotels, cinemas, television etc., so in or around 1961 it changed its world-wide name to Electrical & Musical Industries Ltd. (EMI). Most of the companies, including Gramophone Co of Pakistan Ltd, changed their names to EMI (name of country) Ltd. By that time, the Indian company had established a vast global export network and my friend, Bhaskar Menon, then CEO of GC India Ltd, felt that he would lose a lot of goodwill by changing its name and managed to convince the HQ not to change the Indian company’s name. So unlike Pakistan and other factories of EMI International, our Indian counterpart managed to retain its original name, although it remained a 100% subsidiary of EMI International UK, while the Pakistani arm was 60% British and 40% Pakistani. Most importantly though, despite India and Pakistan on daggers-drawn status politically, EMI (Pakistan) Ltd and Gramophone Co of India Ltd continued to operate cordially as sister companies.

SK: Truly fascinating. However, I am afraid, we will have to bring this session to a closure. I never cease to be impressed by your sharp memory and your attention to details. Well, I have done my good deed for the day and am hoping that our article is released this month itself.

RL: Well, I am done with this edition and look forward to part 4. I know you have reminded me more than once on my interaction with Madam Noor Jehan. Thank you for taking me along on your journey and for stimulating and encouraging me to unfold. Stay blessed!

(Karachi-born, Boston-based Siraj Khan is a connoisseur of Southasian films and music. He believes in art and culture as essential bridges between people and places. A global finance and audit specialist by profession, he has written scripts and directed concerts across the USA, UK, Southasia and UAE. He sits on the board of several nonprofits and charities in America, Pakistan and India and has been recognized for his work towards women’s empowerment and services to children and youth. )