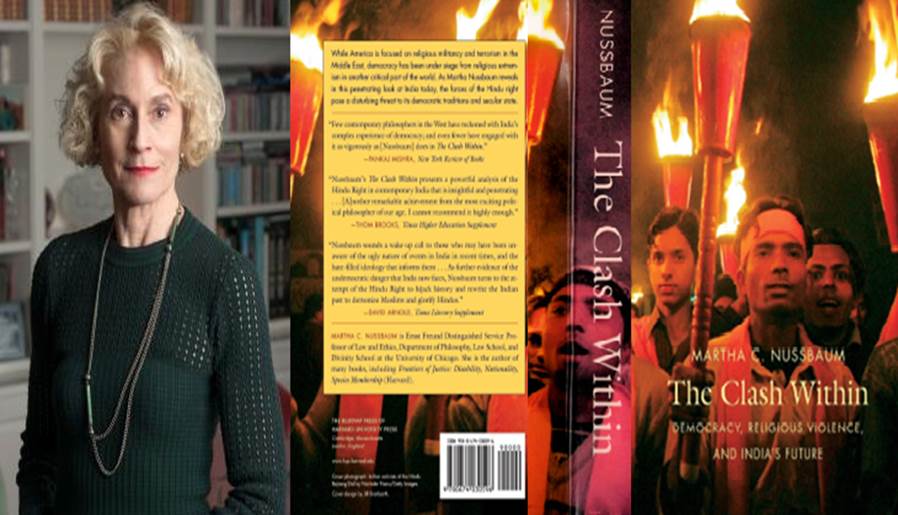

Book & Author

Martha Nussbaum: The Clash Within: Democracy, Religious Violence, and India’s Future

By Dr Ahmed S. Khan

Chicago, IL

“This is an extraordinarily interesting book on a very difficult subject. Martha Nussbaum's commanding familiarity with culturally related political issues across the world, past and present, combines immensely fruitfully here with her involvement and understanding of India.” ― Amartya Sen, Harvard University

The Clash Within — Democracy, Religious Violence, and India’s Future by Professor Martha Nussbaum presents an in-depth analysis of the role of Hindu right — viz a viz religion, politics, philosophy and law — in undermining democratic norms and attenuating pluralism in contemporary India. Professor Nussbaum expounds —through her narrative based on qualitative data and analysis — while America is focused too much on the Middle East, democracy has been under threat from religious extremism in another critical part of the world — India, where the Hindu right poses a major threat to its democratic traditions and secular identity. Since long before the 2002 Gujarat riots — in which thousands of Muslims were killed by Hindu extremists —the power of the Hindu right, led by Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), has been growing, threatening India's secular democracy and jeopardizing coexistence by seeking the subordination of other religious groups especially Muslims — who are labelled as troublemakers and alien polluters, who need to be purged at all costs to attain a “pure” India. The Hindu extremism and exclusivity pose a serious threat to peace and harmony in South Asia.

Martha C. Nussbaum is the Ernst Freund Distinguished Service Professor of Law and Ethics, appointed in the Law School and Philosophy Department. She received her BA from NYU, and her MA and PhD from Harvard. Professor Nussbaum has taught at Harvard University, Brown University, and Oxford University. She is the recipient of three of the world’s most significant awards for humanities and social science — the Kyoto Prize in Arts and Philosophy (2016), the Berggruen Prize for Philosophy and Culture (2018), and the Holberg Prize (2021).

Professor Nussbaum is a prolific writer. She has authored/edited twenty-one books and published over 500 articles. Her major works include: The Fragility of Goodness: Luck and Ethics in Greek Tragedy and Philosophy (1986 & 2000); Love's Knowledge (1990); Poetic Justice (1996); For Love of Country (1996); Cultivating Humanity: A Classical Defense of Reform in Liberal Education (1997); Women and Human Development (2000); Upheavals of Thought: The Intelligence of Emotions (2001); Liberty of Conscience: In Defense of America’s Tradition of Religious Equality (2008); The New Religious Intolerance: Overcoming the Politics of Fear in an Anxious Age (2012); The Monarchy of Fear: A Philosopher Looks at Our Political Crisis (2018); and The Cosmopolitan Tradition: A Noble but Flawed Ideal (2019); and Justice for Animals: Our Collective Responsibility (2022).

The author notes that during the last three decades many academics have focused on the theme of “clash of civilizations” — but they failed to examine the eruption of cultural and religious conflicts within democracies around the world. The author — a well-informed outsider and a friend of India — looks inside India and builds a powerful profile of Hindu right and its rage against foreign conquests. The author presents her narrative — covering a wide spectrum of topics — in ten chapters: 1. Genocide in Gujarat 2. The Human Face of the Hindu Right 3. Tagore, Gandhi, Nehru 4. A Democracy of Pluralism, Respect, Equality 5. The Rise of the Hindu Right 6. Fantasies of Purity and Domination 7. The Assault on History 8. The Education Wars 9. The Diaspora Community, and 10. The Clash Within.

In her preface, describing the audience and objective of the book, the author observes: “This is a book about India for an American and European audience. One of its central purposes is to bring to the attention of Americans and Europeans a complex and chilling case of religious violence that does not fit some common stereotypes about the sources of religious violence in today's world. Its second and larger aim is to use this case to study the phenomenon of religious violence and, more specifically, to challenge the popular ‘clash of civilizations’ thesis, notably articulated by Samuel P. Huntington, according to which the world is currently polarized between a Muslim monolith, bent on violence, and the democratic cultures of Europe and North America. India, the third largest Muslim nation in the world (after Indonesia and Pakistan), is far from fitting this pattern. Instead, in the Gujarat pogrom of 2002, we find the use of European fascist ideologies by Hindu extremists to justify the murder of innocent Muslim citizens. Through a study of this case, its historical background, and the ideological debates surrounding it, I argue that the real clash is not a civilizational one between ‘Islam’ and ‘the West,’ but instead a clash within virtually all modern nations—between people who are prepared to live with others who are different, on terms of equal respect, and those who seek the protection of homogeneity, achieved through the domination of a single religious and ethnic tradition.”

Describing her faith and interest in India, the author states: “(I am a rationalistic Reform Jew who thinks of the moral law as the core of what religion is about.) My interest in India began in 1986 during my work with Amartya Sen, and the passion for justice that has animated Sen's career is also the motive that leads me to love India. My first writing on India was an article co-authored with Sen, concerning cultural traditions' internal self-criticism. Sen's own interest in India's traditions of criticism, rational debate, and public deliberation shaped my own relationship to India from the first, as did my deep ties to the culture of Santiniketan and the legacy of Rabindranath Tagore—not to mention my long engagement with the energy and creativity of the Indian women's movement. As a young girl, I was ill at ease with my elite WASP heritage, which traced its origins to the Mayflower… Just as I converted to Judaism, married a Jew, and joined the cause of the underdog in my own country, and just as I take delight in the comparative noisiness and emotional openness of American Jewish culture, so too I am sure that my passion for India (and particularly for Bengali culture) reflects a similar enthusiasm for the colonial underdog; for the freedom struggle, which I celebrate enthusiastically every August 15; and, very significantly, for the emotional openness and sheer love of talk that I associate with Indian (perhaps especially Bengali) social life.”

Reflecting on the massacre of Muslims in Gujrat (What Really Happened at Godhra) the author observes: “Both theories of the crime should have been dispassionately investigated. They were not, because a panic against Muslims had been successfully spread by political forces. Now that the investigation has been completed by two independent groups, the overwhelmingly more likely story is that negligence and accident were the primary causes. It has proven very difficult to secure justice for the victims of Gujarat. So many witnesses to the crimes were themselves killed; so many delays occurred in the registering of complaints and the taking down of evidence; so many victims had lost their homes and moved away from the area. Added to these difficulties was the widespread use of fire, which destroyed most of the forensic evidence that might have been gathered…The national BJP government made no effort to conduct a serious investigation into the crimes and repeatedly refused calls for Modi’s resignation, even after the electoral defeat of May 2004. Gujarat has been called a ‘blot’ and a ‘blemish,’ but the killings have never been given the strong moral and legal condemnation they deserve.”

Reflecting on her talk with Devendra Swarup, RSS Scholar, the author notes: “Swarup and I talk about many aspects of Indian politics and Constitutional history, but a focus on the danger posed by Muslims rapidly emerges. Like Shastri, he insists that Hindutva is not a race-based ideology but rather a cultural one, "rooted in patriotism, in spiritual value, mid in character building," values that, in his view, must be transmitted through a participatory movement, because they can be learned only behaviorally and "through contact." The basic RSS idea, he says, is to live not for one's own group, but "for some higher group of humanity for my nation, for mankind, and I'm ready to gradually sacrifice my personal and family interest for a bigger cause . . . This comes from an intense feeling of patriotism. In RSS methodology patriotism was the key point . . . You see in this country there are so many languages, forms of worship, castes, the country is vast, so there is also regional tradition. So, in all this diversity it is only intense patriotism for the Land which can unite us…The Islamic identity everywhere in the world is a disruptive and separatist ideology. You see that all over the world. I am not aware of any country; where the Muslims have been able to live in peaceful coexistence with non-Muslims. Do you know of any country?”

In chapter titled “Tagore, Gandhi, Nehru” the author comparing the strengths of three “founders” observes: “Ultimately I shall argue that India's strength as a democrat owes much to each of the three men: to Tagore's prescient and sub thought about religious pluralism, his development of a school that focused on critical thinking and the development of sympathy, and creation of a "public poetry" in which to embody the vision of a pluralistic vision; to Gandhi's passionate egalitarianism, his rhetorical brilliance, and his compelling critique of the desire for domination; and to Nehru's practical political vision, his personal integrity as a lead and his (qualified) embrace of a non-Gandhian yet still egalitarian, modernity. All three rightly saw the "clash" that the new democracy faced as one among groups of different sorts within the society, as well among different desires and tendencies within the individual self.”

Commenting on the faults of the three founders, the author states: “In each, however, one can locate faults that help explain the rise and limited success of the Hindu right. Tagore's educational experiments, so crucial for a budding democracy, failed to spread outside Bengal, in part because of his own unwillingness to delegate leadership to others. Gandhi's repudiation of modernity led to no constructive economic program, and his asceticism led to a vision of gender relations that was not helpful in forging an inclusive democracy. Nehru economic policies often come in for criticism, and some of this criticism is justified. A deeper fault, however, has less frequently been discussed. His disdain for religion, together with his idea of a modernity based upon scientific rather than humanistic values, led to what perhaps the most serious defect in the new nation: the failure to create a liberal-pluralistic public rhetorical and imaginative culture whose ideas could have worked at the grassroots level to oppose those of the Hindu right.”

The author starts the chapter titled “The Rise of The Hindu Right” by citing a quote of M.S. Golwalkar (Bunch of Thoughts): “To remain weak is the most heinous sin in this world,” and observes: “In 1992 there were 33,000 RSS shakhas in India. All over the country, but particularly in the northern and western states, the organization quietly laid down firm roots through discipline, energy, and concerted grassroots work. The philosophy of the shakhas is both simple and sophisticated: lure boys in with fun and games, and gradually insert into games the essential values of the RSS: discipline, obedience and the idea that the future of India depends on unity among Hindus and the marginalization of alien groups. Movement architect Golwalkar compares the strategy to that of a man who wants to get a peacock to visit his garden regularly. He gives the peacock food mixed with opium. Soon it is addicted, and it returns every day.”

Expounding further on the modus operandi of brainwashing young kids, the author states: “So in this local branch: boys have so much fun that they don't mind what the teachers want to teach. Lalit, the most appealing of the three instructors—possibly because of his sense of humor and certain lightness of touch—observes, ‘You can teach a lot of things to young kids, like what the RSS is about, the problems facing the nation, and those created by the Congress Party. So, you have many things.’ They begin, he says, by playing a lot of tiring games to get the boys ready for control…. The boys turn to politics. ‘Whom does Kashmir belong to?’ Instructors. ‘To us,’ shout the boys, giggling. ‘Whom does It belong to?’ ‘To us,’ they shout louder. And should a temple be built at Ayodhya, displacing the mosque that is currently there? ‘Yes,’ says one boy, ‘it should be built and there should be unity. There shouldn't be a mosque there.’ ‘The Muslims already have a mosque,’ adds another boy. Kali agrees that the temple should be built, ‘because we are united in this, we worship the Lord’ (that is, Rama). Already they have learned about a unity that excludes. Now we see one of the instructors take the oath of RSS membership…”

The author notes that India has been far more fortunate than Pakistan in the caliber of the people it elevated to power, and also very shrewd in its choices, furthermore, the education system in India should not be based on rote learning and BJP’s politically authored textbooks, rather they should promote critical thinking.

The Clash Within — Democracy, Religious Violence, and India’s Future by Professor Martha Nussbaum is an important work that negates Samuel P. Huntington’s thesis of ‘clash of civilizations’ and builds a case for “clash of cultures and religions within a country,” and presents an in-depth analysis of democracy and religious extremism in contemporary India. It is an essential read for students of history as well as general readers.