Hanif Mohammad batted 16 hours 10 minutes, the longest Test innings which remains unbroken till this day. In the time spent in the middle, covering 9 consecutive sessions — enough to encompass almost 11 separate football matches.

Hanif Mohammad's Incredible 16-Hour Effort to Save a Test Match for Pakistan at Bridgetown

By Arunabha Sengupta

(On January 23, 1958, Hanif Mohammad rewrote the record books with an innings that was miraculous in terms of tenacity and concentration. Arunabha Sengupta revisits the 970-minute epic at Bridgetown with which the original Little Master miraculously saved the Test match by batting for nine consecutive sessions.)

Till the middle of the third day, the Bridgetown Test followed a conventional script.

A phenomenally strong West Indian batting line up sent the touring Pakistanis on a leather hunt. Conrad Hunte belted 142 on debut, hitting 50 of the first 55 runs scored in the match — even though the batsman who stood at the other end was Rohan Kanhai . Everton Weekes plundered a strokeful 197, the last hundred of his fantastic career. Collie Smith and Garry Sobers registered half centuries, and Clyde Walcott chipped in with 43.

Nasim-ul-Ghani set the record for the youngest Test debutant, at 16 years and 248 days, but had to return wicketless. And when the innings was closed at 579, Roy Gilchrist, Alf Valentine and the rest of them rushed out to pick up the wickets.

The Pakistanis, tired after two long days under the sun, surrendered meekly. After all, they had started playing Test cricket for just six years. On foreign turfs, they were expected to be minnows. On the morning of the third day, the wickets fell in a heap. Gilchrist knocked over four. Collie Smith’s leg-spin captured three. The swing of Eric Atkinson and the left-arm guile of Valentine made dents as well. The Pakistan innings folded for 106.

Saving the match was in the domain of impossibility. Not only was the deficit a monumental 473, it was also a six-day Test match. Three and a half days stretched ahead, a looming infinity in cricketing terms. Gilchrist, with his fierce run up, extreme pace and dodgy action, was raring to go once again.

And then the script went haywire, twisted out of the confines of reality, into the make-believe world of fairytales.

Twenty-three-year-old Hanif Mohammad took guard. Perhaps moved by the boyish looks of the diminutive batsman, the veteran Walcott had passed on some valuable advice ahead of the innings: "Never try to hook Gilchrist." Hanif started swaying away as the intimidating fast man bowled a barrage of bouncers.

It paid off. At the other end, wicketkeeper Imtiaz Ahmed put his head down. And Hanif delved into his immense powers of concentration. Eric Atkinson did trouble Hanif at first. "He used to put a lot of cream in his hair. That may have had something to do with the fact that he managed to swing it both ways, and swing it late," Hanif recalled years later. However, the Pakistani openers stuck to their task.

In the final minutes of the day, Gilchrist brought one back to trap Imtiaz leg before for 91. Pakistan ended the day on 162 for 1. Hanif was battling on at 61.

With three full days to go, no one really gave them a chance to save the match. Even that exemplary leader of men, Pakistan’s captain, Abdul Hafeez Kardar, spared himself the trouble of a pep talk. All Hanif got from the skipper was a note beside his bed that said, "You are our only hope."

It was under scorching heat when Hanif resumed his innings the next day. Heat that made layers of skin peel off under his eye as he batted on and on. With time, he tried to farm as much of the strike as possible. The West Indians kept coming at him, using bowler after bowler. At the other end Alimuddin restrained his attacking instincts and scored an uncharacteristically patient 37 before Sobers induced an edge off him. The second wicket stand had produced 112.

Hanif carried on, with debutant Saeed Ahmed joining him in the middle. Over after over were bowled, the pitch started to show signs of wear and tear — some balls splitting the ground and rising sharply. But, nothing could

sway Hanif Mohammad. He stood like the "Sentinel of Eternity", stretching the concept of time — much like Arthur C. Clarke had done a few years earlier in his work of science-fiction bearing the same name.

At the end of the fourth day, Hanif was unbeaten on 161, having scored exactly hundred during the day. Pakistan were 339 for two. Yet again he received a note from Kardar in the evening which simply said, "You can do it."

With two days still remaining, the match was not safe by any means. In came the West Indian bowlers again. Denis Atkinson bowled marathon spells. Clyde Walcott was asked to roll his arms over. Valentine tried to pull out every scrap of devious cunning from his huge bag of tricks. But Hanif could not be budged.

Saeed departed at 418, nicking a leg break from Smith. Hanif was joined at the wicket by elder brother Wazir. The day wore on, hot and sultry. Time stood still as Hanif stood at the crease, impregnable in defense, exquisite in technique and immovable in concentration. The day ended with Pakistan on 525 for 3. Hanif was still there on 270.

The lead was still just 52. A sudden collapse would mean a West Indian victory. The note from Kardar that evening said, "If you can bat until tea tomorrow, the match will be saved." Hanif had already batted for two and a half days. Now he got ready to bat another.

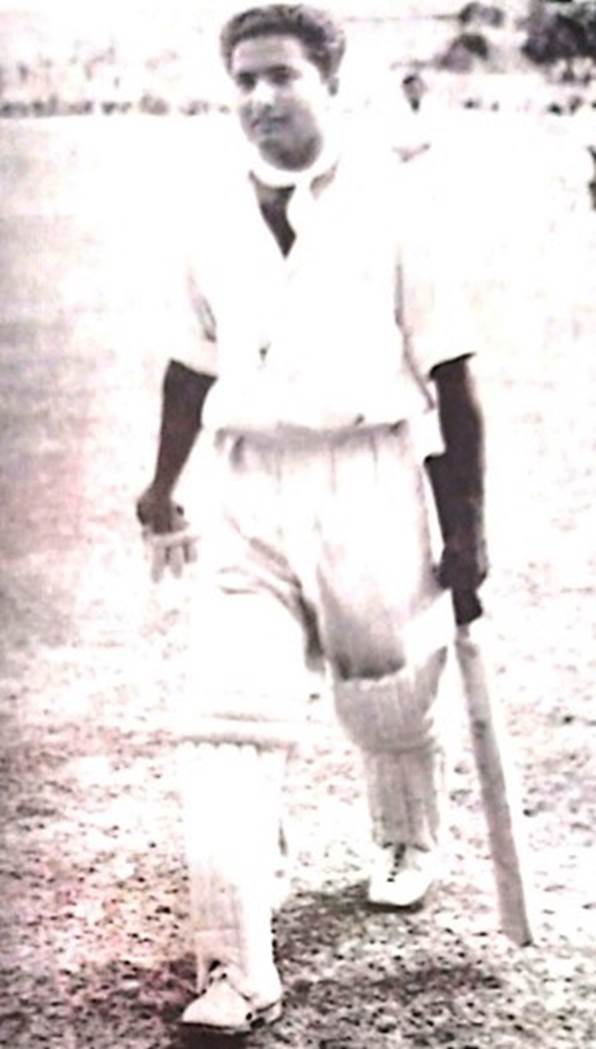

Looking remarkably fresh, Hanif returns to the pavilion after his

marathon innings for Pakistan at Bridgetown in 1957-58

Wazir left for 35, caught behind off Eric Atkinson. But his younger brother went on batting. By now, the crowd — initially antagonistic towards Hanif’s relentless vigil — was thoroughly behind him. From all quarters of the stands full to the brim, and trees overpopulated with climbing fans, came all sorts of advice and encouragement. There were at least ten voices that told him how to play Gilchrist. Pakistan went in to lunch at 566 for 4. Hanif was on 297.

After the break, having batted for 14 hours 18 minutes, Hanif reached 300. The crowd now roared with approval.

Wallis Mathias was now trapped plumb by a late in-swinger from Eric Atkinson. Captain Kardar came out to join Hanif in the middle. And at Tea, Hanif had fulfilled his captain’s wishes, still there unbeaten on 334. The score now was 623 for 5. The match was safe.

Hanif had already rewritten the record for the longest innings in the history of the game, eclipsing Len Hutton’s 797-minute epic at The Oval scored two decades earlier. However, now Hutton’s 364 seemed to be within reach. The batsman set his eyes on the world record as he resumed his innings after Tea.

He had progressed to 337 when a ball from Denis Atkinson jumped up, kicking some dirt off the wicket, took the shoulder of his bat and went to Gerry Alexander behind the stumps. The 970- minute tale of phenomenal concentration had come to an end. Hanif Mohammad, three layers of skin peeled from under his eye in the heat, walked back amidst tremendous applause, the sweat drenched handkerchief tied to his neck, still looking remarkably fresh.

The innings had lasted 16 hours 10 minutes — although Hanif always maintained it had been 999 minutes. In any case, it had rewritten the record of the longest Test innings by three hours — and remains unbroken till this day. In the time spent in the middle, covering nine consecutive sessions and enough to encompass almost eleven separate football matches, he had hit 24 boundaries, and run 105 singles, 44 twos and 16 threes.

Fazal Mahmood came in and hammered a couple of sixes before Kardar closed the innings. The West Indian openers played out the remaining few minutes. The match ended in a draw.

Not perfect — but very nearly so

Hanif’s mammoth effort lives on till this day, 55 years down the line. Peter Roebuck included it in his book Great Innings, awarding it highest marks for courage and heroism. In a 2002 ranking published by Wisden in 2002, Steven Lynch recognized it as one of the three greatest Test rearguards of all time.

One of the folklores that have developed around the effort is that the innings was technically perfect; the ball never once even touched his pads. Hanif Mohammad himself later dismissed that as a myth. "It did (strike my pads) a few times. The wicket had deteriorated. Occasionally, there would be a ball that hit a rough spot and knocked some dirt from the surface. That would make me miss the line. On one such delivery, I even thought I was in danger of being lbw-ed. But fate was with me," he recounted in an interview given to Dawn on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the innings.

Hutton’s record survived the scare, but not for long. In the third Test match of the same series, barely a month later, Garry Sobers notched up an unbeaten 365.

West Indies 579 for 9 decl. (Conrad Hunte 142, Garry Sobers 52, Everton Weekes 197, Clyde Walcott 43, Collie Smith 78; Fazal Mahmood 3 for 145, Mahmood Hussain 4 for 153) and 28 for no loss drew with Pakistan 106 (Roy Gilchrist 4 for 32, Collie Smith 3 for 23) and 657 for 8 decl. (Hanif Mohammad 337, Imtiaz Ahmed 91, Saeed Ahmed 65).

( Arunabha Sengupta is a cricket historian and Chief Cricket Writer at Cricket Country. He writes about the history and the romance of the game, punctuated often by opinions about modern day cricket, while his post-graduate degree in statistics peeps through in occasional analytical pieces. The author of three novels, he can be followed on Twitter at http://twitter.com/senantix )