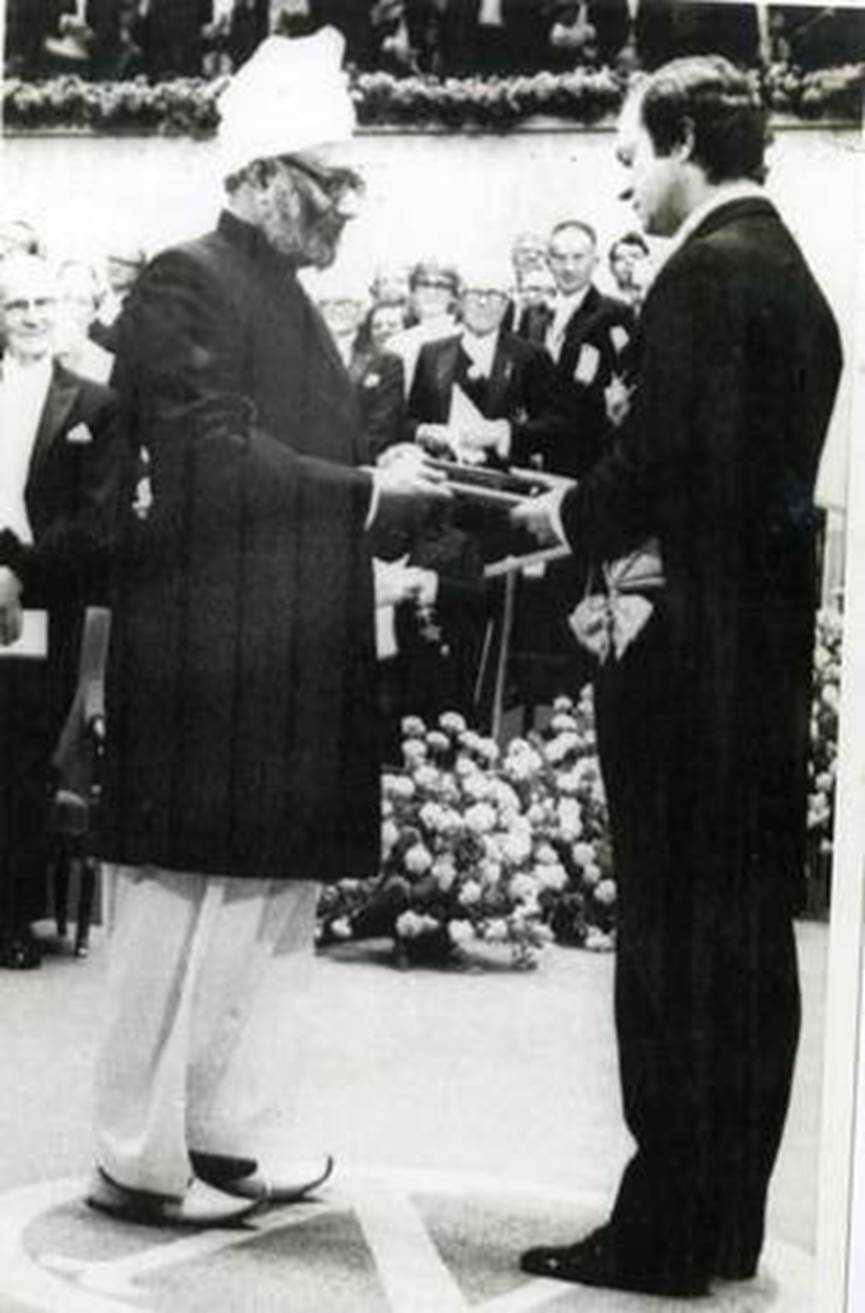

Professor Abdus Salam receives the Nobel Prize

From Jhang to Trieste: The Untold Story of Dr Abdus Salam

By Asif Javed, MD

Williamsport, PA

When Dr Abdus Salam walked to the stage in December 1979 to receive his Nobel Prize, he broke from tradition. Instead of the customary suit with white tie, he wore the traditional Punjabi dress with a "shamla turban" and a "gold khussa shoe". This may have been a demonstration of his pride as well as humility for a scientist born in a two-roomed mud house without electricity in the peripheral town of Jhang.

In the Nobel lecture that followed, he described in vivid detail the great heritage of Muslim scientists: men like Ibn Rushd or Avorros, Ibn Seena and many more. When the news of his Nobel award flashed on the TV screens across the world, he became known to the millions instantaneously; for the select few who had known him in his profession, he had arrived decades earlier.

Some time ago, this writer asked a few physician colleagues - all from Pakistan -- of what they knew about Dr Abdus Salam. The answers went like this: he won the Nobel Prize, lived abroad, was Ahmadi, and that pretty much summarizes it. To my amazement and shame, I knew only a little more. It was with this background that I recently read a biography -- Cosmic Anger by Gordon Fraser -- of this great son of Pakistan and would like to share some aspects of his life with Link's readers.

Dr Salam's ancestors converted to Islam from Hindu Rajputs a few hundred years ago. His father, Mohammad Hussain, was a schoolteacher in Jhang. His paternal uncle Ghulam Hussain, later to become his father-in-law, was the first to convert to the Ahmadi sect. The other family members later followed. Salam, therefore, was born into this sect and did not convert himself.

His academic journey took him from the backward waters of Jhang to Government College Lahore, Cambridge, Princeton, back to Lahore and back again to Cambridge, Imperial College London, and Trieste Italy. The list of his academic accomplishments is very long. Suffice it to say that what started as a first position in class one continued to the award of the Nobel Prize, KBE and well beyond. Cosmic Anger is a well-written, balanced and well-researched book that makes interesting reading.

Salam comes across as a very motivated, deeply religious and hardworking individual. We learn that he had a "monk like devotion" to duty and worked up to 16 hours a day.

For him, time was a very precious commodity that could not be squandered. The most productive part of his day was early morning. The day began with prayer. He was an avid reader and did a lot of reading outside physics and math. He had been coached in poetry at Jhang by Sher Afzal Jafery. At the Government College, he had been president of the college union, editor of the college magazine `Ravi', and played chess. He stayed in the famous New Hostel -- which he visited after his Nobel award - to personally thank his servant Saida who had looked after him in his student days. We also learn that he fell in love with Urmilla, the beautiful elder daughter of the college principal Sondhi. We will never know whether she ever responded to his charm or whether he ever approached her. Perhaps he did not, and if so, it may have been like Meeraji's distant liking for the obscure Bengali beauty Meera Sen, but that is a story for another day. Unlike Meeraji, however, Salam moved on to better things in life; for that, we are all very grateful to him for he had too much work ahead of him.

Salam's family was in no position to afford his higher studies abroad. This was made possible by legislation proposed and passed by the efforts of Ch Khizer Hayat Tiwana. It was Mr Tiwana who suggested using leftover money -- originally raised for the Second World War effort --- to pay for the higher education of deserving students. Ch Khizer Hayat Tiwana rarely gets a kind word in our history books. By this action alone, he made it possible for Salam to move on to Cambridge and the rest is history.

Salam' arrival at Liverpool Docks in 1947 on a cold autumn day in a ship that had departed from Bombay weeks ago, was a very uncomfortable one. The young man on his way to Cambridge with a trunk load of books was ill-prepared for the cold British weather and was struggling to move his luggage when he was spotted by Sir Zafarullah Khan who had come to receive a nephew.

Having seen the young man's predicament, Zafarullah offered help.

That included giving his overcoat to Salam.

They traveled to London together in the train and stayed together overnight in a mosque in Southfields, London before Salam continued his journey to Cambridge the following day. That was not the first time Zafarullah had given help or advice to Salam. Years before, Salam's father had sought advice from Sir Zafarullah about Salam'shnnnhhn career. Zafarullah offered three very valuable pieces of advice: firstly, the family should take good care of Salam's health; secondly, lessons should be prepared beforehand and revised after school; and lastly, the boy should be made to travel to broaden his outlook.

Sound advice, indeed! Dr Salam and Zafarullah were to develop a very personal friendship over the years.

Reading this biography, Zafarullah comes across as one of the most influential persons in Salam's life, the others being his father, and Paul Dirac, a famous physicist whom Salam considered the greatest scientist of the 20 century, even above Einstein.

Salam's life had its fair share of failures and tragedies. An amusing one was his failure to pass the dreaded British driving test on first attempt. He failed to do the parallel parking to his examiner's satisfaction. To the genius from distant Jhang who had always stood first, that must have appeared strange.

Many more setbacks were to follow, however. We learn how Salam and his family were threatened during the 1953 anti-Ahmadi riots in Lahore. At the time, he and his family resided on the campus at Government College where he was Professor of Mathematics and had to be smuggled out of their residence for safety. Ironically, there is a hall in Government College named after him now; such are the ways of this world.

Salam won the Nobel Prize in 1979. However, what is not commonly known outside the scientific community is the fact that Salam came within a whisker of getting it in 1956 were it not for sheer bad luck. At the time, he had come up with the theory of "massless neutrino" and was ready to send it for publication.

As an afterthought, Salam sought advice from Wolfgang Pauli -- widely considered the biggest name in Physics at the time -- who advised against its publication. Heeding the heavy weight physicist's advice, Salam held on to his paper for some time. As it was, the same theory won the Nobel Prize for Lee and Yang while Salam had to wait another 25 years to finally get his.

Salam's biography makes it abundantly clear that he was after a lot more than just the Nobel Prize.

The International Center for Theoretical Physics has been a spectacular success and was named after Prof Salam posthumously

It appears he had multiple goals: Firstly, to explore the mysteries of the universe to better understand Allah's creation; secondly, he desperately wanted to promote scientific research in the Islamic world; and thirdly, he was keen to create an institution that could enable the Third World physicists to come together to exchange ideas, interact and to reverse the brain drain to the West. There is no question that he succeeded in achieving the first objective; his Nobel award proves that.

Salam also succeeded in creating the International Center for Theoretical Physics (ICTP) in Trieste, Italy that met the third goal. The International Center for Theoretical Physics has been a spectacular success and was named after him posthumously. It was in the promotion of science in the Muslim world that Salam tragically failed.

Salam travelled far and wide in the Islamic world and left no stone unturned to plead his case. He made multiple trips to the oil-rich Middle East but without success. There were not many Muslim heads of state with the vision to understand his point of view. Part of the problem was his Ahmadi faith. Salam continued to carry a Pakistani passport all his life that declared him a "non-Muslim". He could have easily become a British or Italian citizen but didn't choose to do so. This made him go through the long immigration lines at London's Heathrow airport followed by interviews with the arrogant immigration officers. He endured all that humiliation in his single-minded devotion to his goals in which he partially succeeded.

Salam died of PSP, a degenerative disease of the brain, in 1996 at his second wife's home in Oxford.

Though very debilitated and limited in his mobility and speech, his mind was sharp up to the very end. His dead body, accompanied by family members, was flown to Lahore where true to tradition, no high-ranking member of the government or politician, was present to receive it or to later attend his funeral. This nation had disowned him along with his entire Ahmadi community years ago, branding them as heretics. At least, he was in good company for a similar fate had befallen Galileo Galilee.

Today, the man who brought a Nobel Prize for our nation lies buried in a simple grave in Rabwa where this writer had the opportunity to offer Fateha a few years ago. His death anniversary comes on November 21 and passes away without much notice.

Late Khalid Hassan wrote a very moving tribute to Sir Zafarullah a few years ago. Let me quote from his lines, "This nation has not had the grace to acknowledge, much less thank, its real heroes. Will that ever come to pass? One can only wonder".

(The writer is a physician in Williamsport, PA, a Sunni Muslim, and can be reached at asifjaved@ comcast.net.)