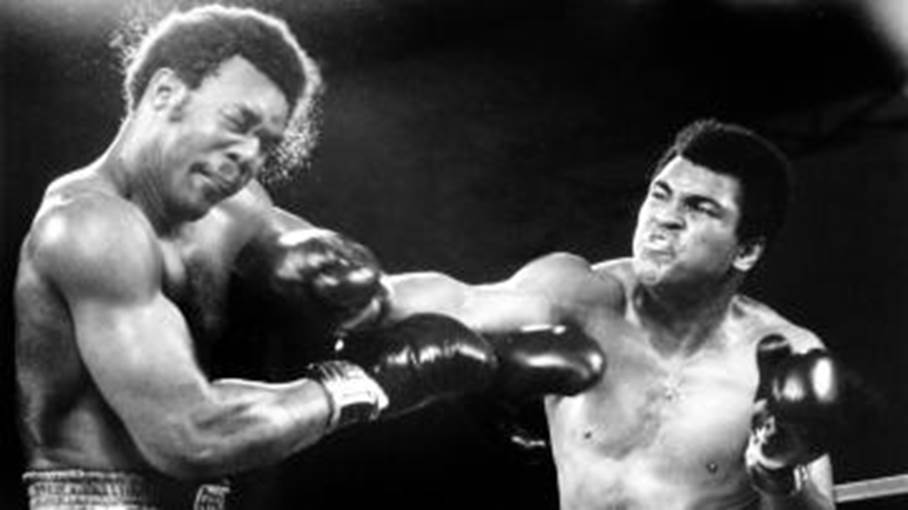

George Foreman and Muhammad Ali during the Rumble in the Jungle, 1974 – ALAMY

A Chance to Relive the Rumble in the Jungle

By Clive Davis

When Norman Mailer wrote his ringside account of the 1974 showdown between Muhammad Ali and George Foreman, he called it simply The Fight. But there was much more to that extraordinary heavyweight championship bout than just sporting prowess. This was a story of politics, race and money. Ali’s charisma and sheer courage — hardly anyone expected the ageing challenger to win back his title against a fearsome, much younger champion — lifted the bout into the realms of high drama.

Here was the most famous man in the world, marching out to do battle in the middle of the night in Kinshasa, capital of what was then known as Zaire but is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo. (The country’s dictator, Mobutu Sese Seko, had paid millions to stage the bout.) What we saw that night, as Ali pulled off a surprise victory, knocking out the previously unbeaten champion, was an unforgettable display of artistry and cunning. It was, in short, the most visceral, profoundly moving performance, sporting or cultural, that I’ve ever seen.

There’s already been an Oscar-winning documentary — When We Were Kings from 1996 — telling the story of that remarkable night. Now it’s the turn of immersive theatre-makers to bring it back to life. Rumble in the Jungle Rematch, which opened to the public in London’s Docklands, comes from the same company that won acclaim for Wimbledon Rematch 1980, a recreation of the classic men’s final between Bjorn Borg and John McEnroe. At that show, held in the Troubadour Wembley Park Theatre in 2019, audiences watched a choreographed version of the match while also sampling the retro delights of Eighties-era drinks and consumer gadgetry.

Actors choreograph their moves in front of a screen showing the real Ali and Foreman

At the latest event, held in a warehouse-like complex, the director Miguel Torres (a veteran of Secret Cinema) and the producer Malú Ansaldo have created a time-travelling spectacle that will give 750 audience members a sense of what it would have been like to wander through Kinshasa’s street markets or hang out at the deluxe hotel where the world’s media killed time in the lengthy build-up to the fight. Actors playing the two boxers choreograph their moves in front of a giant screen showing the real Ali and Foreman.

Other scenes have been scripted by Tristan Fynn-Aiduenu, director of the original version of Ryan Calais Cameron’s acclaimed psychodrama For Black Boys Who Have Considered Suicide When the Hue Gets Too Heavy. Narrators and a cast of characters — some real, some invented — create a patchwork impression of the circus-like atmosphere surrounding the bout, from Ali’s entourage to the showbiz pronouncements of David Frost (who broadcast live from ringside) and the machinations of the brutal and fantastically corrupt Mobutu regime, which used the bout as a form of what we now call sportswashing.

“You can watch the video of the fight on YouTube, but what we’re going to give people is an experience,” Torres says. “It’s not just a fight. I think the advantage of an immersive show is that we don’t have to give a full answer to anything. Each character can be taking a different part of the story.”

He draws a parallel with his experience of visiting Hong Kong to teach a physical theatre workshop during the recent pro-democracy protests. “One day, I was enjoying watching a dragon festival in the streets and then I walked into a bar and met one of the students I’d been teaching. He was upset with the protesters: ‘What the f*** are they doing in the middle of the festival?’ And then I stepped out and met a young boy and he told me why they were protesting. So, I had both points of view and the culture of the country. This is what I want an immersive show to feel like. You can have things happening at the same time. At the end you draw your own conclusions.”

Music provides a backdrop too. In 1974 promoters organized a three-day festival that assembled a stellar line-up including James Brown, Miriam Makeba and Celia Cruz. In a period when the cultural links between Africa and the black diaspora were still sketchy, it was a rare gathering of so many different traditions. In Rematch musicians become an integral part of the action. On the day I visited rehearsals, a band led by the guitarist Femi Temowo — who provided the soulful musical backdrop for the Young Vic’s 2019 revival of Death of a Salesman – was leading the actors through a traditional song.

“I grew up playing the guitar in the Nigerian community here, and we were heavily influenced by the music of Zaire,” Temowo explains. “In the Seventies, Eighties and even the Nineties, it was like what Afrobeat is now. When I started to learn music, I was learning from Congolese musicians. So, it feels so natural to be working on this because that music is second nature to me.

“We’re not only trying to stay true to the music of the artists who performed at the festival, but also the sounds that emanate from the region. A lot of Zairean bands were playing rock’n’roll, funk, blues, gospel. You can always hear their take on it.”

For oldies like me (I was 15 when the original Rumble took place) it’s easy to assume that Ali-Foreman is a part of everyone’s cultural landscape. I box myself and I’ve watched the fight half a dozen times over the years, and still get a knot in my stomach when I watch the fighters step into the ring. For my generation, Ali was a godlike figure who transcended sport through his campaigns for civil rights. But we’re talking about a sporting event that’s half a century old. The Colombian-born Torres, who is 36, admits he didn’t know about the Rumble before he joined the project, although as a music lover he’d seen the footage of Cruz singing with the classic Latin band the Fania All-Stars.

One man who has a very clear memory of the fight is the renowned advertising executive Trevor Beattie, owner of a huge collection of Ali memorabilia and one of the show’s main investors, who also designed its marketing campaign. He arrives at the rehearsal rooms with a suitcase of memorabilia which he shows to cast members. Among the shorts, dressing gowns and magazines are the neatly typed and annotated scripts that the venerable commentator Harry Carpenter used on the night. (The use of “primitive” and “savage” to describe the setting are, you might say, very 1970s.) Later, as we tour the Docklands site — where workers are still constructing the sets, echoing the work-in-progress ambience of Kinshasa in 1974 — Beattie recalls how, as a 14-year-old, he first met Ali when the great man was visiting Beattie’s hometown, Birmingham.

Their paths crossed several times over the years. Beattie, who is now a film producer too (he co-financed the forthcoming biopic about the Beatles manager Brian Epstein), would love to make a film about Sonny Liston, the glowering heavyweight whom Ali beat to become world champion in 1964, a decade before the Rumble. As we walk around fake Kinshasa, Beattie recalls how he tuned in to watch the Rumble when it was shown on BBC1 hours after it had been screened live on closed-circuit TV.

Could that really be nearly 50 years ago? The film-maker Ken Burns’s recent eight-hour documentary series on Ali will have introduced a new generation to his exploits. The sad fact remains, though, for many people, we are talking about ancient history. As Temowo observes, even figures as towering as Ali and Foreman are receding into the distance: “A lot of the young people I’ve spoken to ask, ‘What are you working on?’ ” he says. “And I tell them Rumble in the Jungle. And they say, ‘What’s that?’ Then I start to explain, and they’re like, ‘Oh, like the Will Smith movie?’ And I tell them, ‘Yeah. Kind of, but you get to be in it.’ ”

Rumble in the Jungle Rematch is at Dock X, London, from September 14; rumbleinthejunglerematch.com . - The Times