Book & Author

M. Asghar Khan: We've Learnt Nothing from History— PAKISTAN: POLITICS AND MILITARY POWER

By Dr Ahmed S. Khan

Chicago, IL

Many scholars have wondered about Pakistan and India gaining independence at the same time and yet the two countries’ progress and achievements remain light years apart. India’s civilian leadership swiftly got rid of its colonial legacy and established its economic, educational and democratic institutions; whereas in Pakistan the colonial legacy remained intact in its socio-economic-military fabric, and after the untimely death (September 1948) of Quaid-i-Azam, the founder of Pakistan, and the assassination (October 1953) of Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan, the country was hijacked by constitution-abrogating generals to serve the geo-politics of the time — nothing has changed during past seventy-six years — the military rule continues via direct and indirect modes.

In contrast, India has developed its economic and intellectual capitals — in addition to holding a G-20 summit as its chair, India also exhibited its technological prowess by landing a spacecraft on the dark side of the moon. In Pakistan the economic progress and development continues to be impeded and stunted by the corrupt-to-the-core ruling elite — generals, judges, bureaucrats, tycoons and feudal lords.

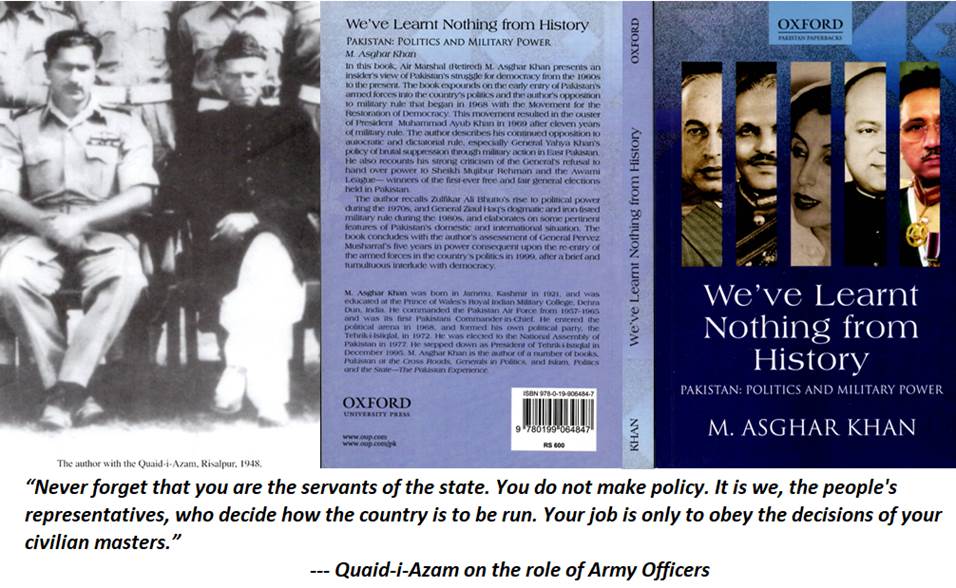

In We've LearntNothing from History— PAKISTAN: POLITICS AND MILITARY POWER, Air Marshal (Retired) M. Asghar Khan (January 17, 1921 – January 5, 2018) presents an insider's account of Pakistan's struggle for democracy (1960-2005) and his continued opposition to autocratic and military rule. The author chronicles the entry of Pakistan’s armed forces into politics when General Ayub Khan imposed martial law in October 1958. The author expounds on General Yahya’s brutal policies of suppression in East Pakistan; his strong criticism of General Yahya’s reluctance to transfer power to Sheikh Mujib ur Rehman — who was the clear winner of the general elections of 1970; he describes Zulfikar All Bhutto's rise to political power (1970s), General Ziaul Haq's military rule (1980s), and his assessment about the’future of democracy in Pakistan; and concludes the book with his critique of General Pervez Musharraf’s five years in power.

The author narrates his insights in twenty chapters: 1. The Quaid-i-Azam as I Saw Him, 2. The Army Enters Politics, 3. How Bangladesh was Born, 4. Rebirth of Democracy, 5. The Guardians of the Law, 6. Pakistan's Second General Elections, 7. Political Dialogue, 8. The Army Digs In, 9. The Real Martial Law, 10. The Hanging of Bhutto, 11. Pakistani Politics and the Role of the ISI, 12. Balochistan in a Federation, 13. Twelve Provinces for Pakistan, 14. The King's Party, 15. Corruption, 16. Devolution of Power, 17. 'Jihad' and the United States, 18. Indo-Pak Relations, 19. The Future of Democracy in Pakistan, and 20. General Musharraf's Five Years in Power.

Commenting on the contents of the book, the author states: “The present book contains some fresh thoughts on the role of the armed forces and the state of politics in the country. Some of this material has been published in national newspapers; it constitutes thoughts on issues that will, in my view, have a profound effect on the country's future and are worthy of attention.”

The book also contains a short biographical profile of the author's son Omar Asghar Khan by Shahrukh Rafi Khan, Professor of Economics at University of Utah. Prof Rafi observes: “Omar Asghar Khan was courageous, pragmatic, humble, soft-spoken, patient, efficient, disciplined, consistent, sincere, and persevering and so much more. He is one of the very few about whom one can say 'he was a prince among men' and his passing away is a great loss to the nation.”

M. Asghar Khan was born in 1921, in Jammu, Kashmir, British India. He was educated at the Prince of Wales's Royal Indian Military College, Dehra Dun, India. He commanded the Pakistan Air Force (1957-1965) and was its first Pakistani Commander-in-Chief at the age of thirty-six. He also served as President of Pakistan International Airlines (PIA: 1965-1968). During his tenures at PAF and PIA his dynamic leadership transformed both organizations into highly efficient world-class entities. He entered politics in 1968 and in 1972 formed his political party, the Tehrik-i-Istiqlal. In 1977 he got elected to the National Assembly of Pakistan. In 1995 he stepped down as President of Tehrik-i-Istiqal. He has authored several books which include Pakistan at the Crossroads, Generals in Politics, and Islam, Politics and the State—The Pakistan Experience. Air Marshal Muhammad Asghar Khan is remembered for his professionalism, honesty, integrity, moral courage, character and dynamic leadership.

The author recalls his two meetings with the Quaid-i-Azam. Remembering his first meeting in Delhi when Quaid-i-Azam made for him the most important decision of his life. The author was serving as Officer Commander of Delhi's prestigious 9th Squadron —he was concerned about his future in the Indian Air Force in November 1945 — disappointed by the bureaucratic red tape he was inspired by Sukarno's anti-imperialist campaigns against the Dutch. The author was ready to leave for Indonesia when he found himself walking four miles to the Safdar Jung airfield to meet the leader of the Muslim League, Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah… Just before he boarded the Dakota, the author managed to approach the Quaid. The author told him of his dilemma and was hoping for affirmative support, but he was surprised to hear strong opposition: “No, you must not go to Indonesia. Pakistan will need good pilots”, said the Quaid. With those words, Asghar Khan felt his fate had been sealed. “As I walked back”, the author recalls, “I realized I was small fry and he a great man. The simple strength of his words was enough for me never to look back again.”

Recalling his second meeting with the Quaid-i-Azam, the author states: “The second time when I had the opportunity to meet Mr Jinnah and to hear his views on an important subject was on 14 August 1947 in Karachi. As the Governor-General of Pakistan, he had given a large reception on the lawns of the Governor-General's House, now the Governor's House, in Karachi. I was among the dozen or so officers of the armed forces invited and one of the others was Lt Colonel (later Major-General) Akbar Khan of 'Rawalpindi Conspiracy' fame. Akbar Khan suggested that we should talk with the Quaid-i-Azam. The Quaid was moving around meeting his guests and when he came near us, he asked us how we were. Akbar Khan replied that we were very happy that he had succeeded in creating a free and independent country and we had hoped that under his leadership 'our genius will be allowed to flower'. He went on to say that we were, however, disappointed that higher posts in the armed forces had been given to British officers who still controlled our destiny. The Quaid who had been listening patiently raised his finger and said: ‘Never forget that you are the servants of the state. You do not make policy. It is we, the people's representatives, who decide how the country is to be run. Your job is only to obey the decisions of your civilian masters.’”

Reflecting on the imposition of martial law, the author notes: “I was summoned by the president at about 9 p.m. on 7 October. When I arrived at the President's House, I found Ayub Khan and a number of other army officers, amongst them Brigadier Yahya Khan, present there. I was told by Iskander Mirza that he had decided to abrogate the constitution; marital law had been declared and the army was moving in to take over the government. I had no prior knowledge of such a plan and was told that I should stay there for the next couple of hours, presumably until all moves had been completed. The following day I attended a meeting presided over by Iskander Mirza at which Ayub Khan, the chief justice of Pakistan and the newly appointed members of Ayub Khan's cabinet were present. At this meeting, Chief Justice Mohammad Munir was asked by Ayub Khan as to how he should go about getting a new constitution approved by the people. Justice Munir's reply was both original and astonishing. He said that this was a simple matter. In olden times in the Greek states, he said, constitutions were approved by 'public acclaim' and this could be done in Pakistan as well. Ayub Khan asked as to what was meant by 'public acclaim' to which Justice Munir replied that a draft of the constitution, when prepared, should be published in the national newspapers. This should be followed by Ayub Khan addressing public meetings at Nishtar Park in Karachi, Paltan Maidan in Dhaka, Mochi Gate in Lahore, and Chowk Yadgar in Peshawar at which he should hold up the draft of the constitution that had been published in the newspapers a few days earlier and seek the public's approval. The answer, the chief justice said, would definitely be in the affirmative. This, he said, was approval by 'public acclaim'. Most of those present laughed and Ayub Khan laughed the loudest. Although this advice was not followed by Ayub Khan for the approval of his constitution, this is what the chief justice of Pakistan had suggested in all seriousness. No wonder that Pakistan has found it difficult to shake off martial law ever since.”

Commenting on the decline of the Ayub era, the author observes: “Ayub Khan had ruled the country for nearly a decade when, towards the end of 1967, he fell seriously ill. He was unable to discharge his responsibilities and was unconscious for a few days. The constitution of the country, whose architect he himself was, had laid down clearly that in such an event the speaker of the National Assembly, Abdul Jabbar Khan— who happened to be from East Pakistan—would act as president. This, however, did not happen. Ayub Khan had recovered sufficiently by the spring of 1968 to resume his duties but was never his old self again. By October 1968, opposition to Ayub Khan was beginning to mount.”

Expounding on the background of Mujib ur Rehman’s six points, the author notes: “When Yahya Khan took over, he did so against this background, and when he decided to hold elections, he thought it fit to undo the One Unit as well as to concede Mujibur Rehman's demand of one-man-one-vote. This move was popular in East Pakistan as well as in the smaller provinces of West Pakistan who feared Punjabi domination in a One Unit assembly. Having announced the date of elections, Yahya Khan gave political parties full opportunity to propagate their views and put forward their programs. Mujibur Rehman and the Awami League did so with extremist slogans and their election campaign rapidly gained momentum. They advocated complete control over the affairs of East Pakistan, although they could, with one-man-one-vote and the break-up of One Unit, have controlled the whole of Pakistan. Their deep-rooted mistrust of the Punjabi-dominated bureaucracy and the army had, however, convinced them that they could never hope to achieve control of the country. Moreover, the Six Points had by then so captured the imagination of the people of East Pakistan that Mujibur Rehman did not think it possible or desirable to abandon them.”

Reflecting on Yahya’s rule, the author notes: “The thirty-three months of Yahya Khan's rule will be remembered for two important events—the elections of December 1970 and the break-up of Pakistan. -Yahya Khan started his rule with the belief, common among generals in underdeveloped countries, that the solution of the country's political, constitutional and regional problems lay in a military government. He and his close advisers had no concept of a radical socio-economic program required for the country. He was a typical representative of the reactionary military—bureaucratic machine that had by then snugly fitted into the mantle of its British predecessors. However, whereas the British rulers had been answerable to the Parliament in London, Yahya Khan and his associates were answerable only to their own whims. It was tragic that wine and women—in more than ordinary doses—had begun to dull both his brain and conscience to an extent that the affairs of state were neglected. He was willing to leave these matters to the bureaucracy that had been running things for Ayub Khan behind a façade of democracy. In the field of foreign affairs, he, like Ayub Khan, was a staunch believer in the wisdom of remaining allied with the West. He was no admirer of China but found it expedient to continue the policy of friendship that had been established during Ayub Khan's period in power. In fact, Yahya Khan's three years were, in the field of economic and foreign affairs, an extension of the ten years of Ayub Khan's rule. It was in the political field that Yahya Khan exercised new initiatives that were to prove disastrous for Pakistan. Yahya Khan believed that he was a man of extraordinary intelligence and thought that he had the capacity of fooling many people at the same time.”

Describing the importance of following the lawful commands, the author notes: “Throughout my political career and, particularly during Zulfikar All Bhutto's time, on numerous occasions I exhorted the police to obey only lawful commands of their superior officers. It was their duty, I reminded them, to disobey a command that they knew to be illegal. This is intellectual honesty. It does not involve the giving or taking of money…”

Reflecting on devolution of power, the author states: “In Pakistan, since democracy has not been allowed to function, the system has not really changed. When the fountain of power is one single individual, it is inevitable that this reality will be reflected in all tiers of government. This was so when an effort was made in the 1960s to introduce a system of 'Basic Democracy'. It is also largely responsible for the difficulties and the problems being faced with the attempt at the 'Devolution of Power' introduced by the present government. Power has to be devolved from the center if devolution has to have any meaning, and the first step has to be taken by devolving power from the center to the provinces.”

Explaining why power was not handed to the elected majority in 1970, the author states: “As long as East Bengal was a part of Pakistan, there was a powerful political factor which could not be ignored. This was resented by some top Generals in the army and the feudal class of West Pakistan. It was this thinking that led Zulfikar Ali Bhutto and Yahya Khan to refuse to hand over power to an elected majority, thus causing a civil war and the break-up of the country.”

Reflecting on the future of democracy in Pakistan, the author observes: “Pakistan’s population of 140 million will be 250 million in another twenty years, and 500 million by 2050. India's population, which is also expanding at the same rate, will have overtaken that of China and doubled in another twenty years. There will be millions dying of starvation in both countries while politicians continue to mislead their people. Even water will be scarce. It is a frightening prospect that we should address ourselves to. The solution of the Kashmir problem in a manner that would meet the needs of both India and Pakistan will create new opportunities of peace and prosperity for the people of the two countries. Will the leadership of these two countries rise above their personal vanities and narrow political considerations? If they show the vision and the courage to do so, they will save their people from disaster and help the establishment of democracy in Pakistan.”

Commenting on how Generals interfere in politics, the author notes: “In the elections of 2002, the General felt that it was important for him to secure a majority in parliament in order to be able to rule effectively and satisfy national and international public opinion that Pakistan was moving towards a democratic order. In order to acquire the majority, the Inter Service Intelligence agency (ISI), which over the years, largely by the collaboration of political parties, has grown into a powerful parallel government, was used to advise and browbeat politicians to join the King's Party.”

After his visit to Dhaka in July 1971, the author wrote a letter to Yahya Khan: “18 July 1971, Dear Mr President, I have recently returned from a visit to East Pakistan where I was able to meet a large number of people. As a result of these contacts and of my observation of events, I have come to certain conclusions. Some of these I have refrained from discussing in public. I am convinced that time is running out and a change of approach is necessary, if the situation is to be saved. You are no doubt aware that ever since the events of March, I have differed with your Government about the best method of tackling this problem. I am, however, anxious, as many of our countrymen are that a policy should be adopted which is both practical as well as enduring, a policy that has a reasonable chance of success. Should you be inclined to accept my analysis of the situation and listen to a point of view different from that of your Government, I shall be very glad to make myself available at your convenience. Yours sincerely, M. ASGHAR KHAN.”

The author met Yahya Khan when he visited Abbottabad a few days later, and advised him of the dangerous situation in East Pakistan. “I advised him that even at that late hour it would not be unwise for him to seek a political solution and enlarge the scope of his amnesty, which he had already granted, to include all the political leaders of the Awami League who had left the country, so that they could return. I suggested that he should then call a meeting of the National Assembly and transfer power in accordance with the rules he himself had laid down prior to the 1970 elections. I told him that there was no other way to get out of the quagmire. A nobler man than Yahya Khan might have been able to accept this advice, which would logically also have meant his own quittal, but Yahya Khan was not a man of such stature. Both his ego and hunger for power were dearer to him than Pakistan. When I saw that Yahya did not find this suggestion worthy of serious consideration, I suggested that he might at least change the governor. Tikka Khan was an abhorred name in East Pakistan and was associated with the killings that were taking place. Yahya said that he had already decided to do this, and asked me if I had any suggestions for his replacement. Lt.-Gen. Azam Khan had been one of the most successful governors of East Pakistan during Ayub Khan's days and was remembered there with affection. I suggested his name, but Yahya did not favor the idea. It appeared that he had already decided upon…”

The author concludes the book by offering his advice to end the military rule: “So far as Pakistan is concerned, it will continue to suffer under a military dictatorship until the following steps are taken: 1. The 1973 constitution is restored in its original form. 2. The Judiciary is made completely independent. 3. The Armed Forces and the Inter-Services Intelligence cease to have a political role. 4. The Chief of the Army Staff ceases to be the Head of State.” Unfortunately, the generals have failed to pay heed to Air Marshal Asghar Khan’s advice — and the perpetual military rule continues in Pakistan —attenuating the country’s economic progress and stunting its potential.

In We've Learnt Nothing from History— PAKISTAN: POLITICS AND MILITARY POWER, Air Marshal Asghar Khan sheds light on how the generals took over running Pakistan and created a state within the state. It isessential reading by all Pakistanis especially the military officers — so that they can learn something from history and not repeat the blunders their seniors have committed earlier — to end the perpetual military rule for achieving a strong and dynamic Pakistan led by the civilian leadership as envisioned by the Quaid-i-Azam!