Congress leader Rahul Gandhi and Prime Minister Narendra Modi - File photos.

.

A Massive Organizational Challenge: India’s Numerically Mind-Boggling ‘Festival of Democracy’

By Mayank Chhaya

Chicago, IL

As India begins its gigantic parliamentary voting exercise, it is worth noting that the country has the extraordinary distinction of having conducted the world’s largest elections since starting the process in 1951-1952.

India as an independent nation-state got off to a remarkable start by granting universal adult suffrage immediately after its independence from Britain in 1947. It took the United States 144 years and the United Kingdom nearly a century to grant women the right to vote, something India did immediately.

Barely four years later, the country conducted a massive general election between 25 October 1951 and 21 February 1952 during which there were over 170 million eligible voters. Every election in the last 72 years has been progressively bigger, with 2024 accounting for a staggering almost 969 million voters, 215.8 million under the age of 30.

The number of under-30 voters in India alone is bigger than any other country in the world, based on the electorate size of various nations. With over 215.8 million eligible voters in that demographic—197.4 million in the age group 20-29 and 18.4 million in the age group 18-19— that segment of the Indian electorate tops Indonesia, the third largest democracy in the world.

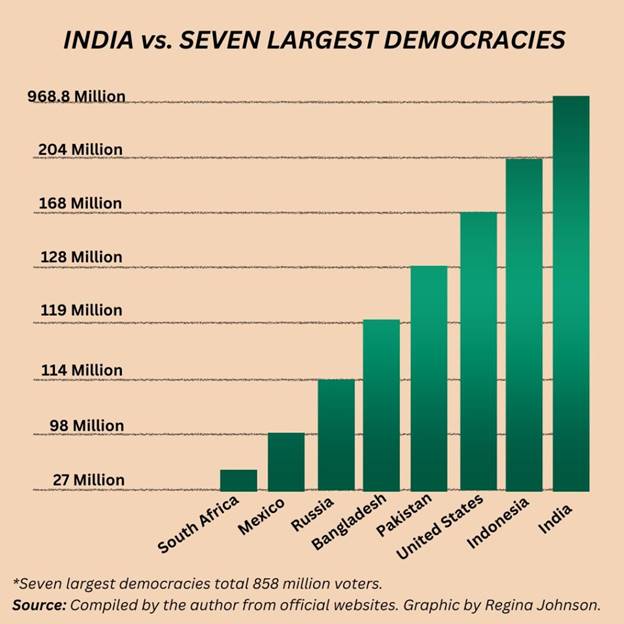

Of course, with India’s total eligible electors numbering nearly 969 million (968.8 million) there is not a country on the planet that has any prospect of matching the distinction of its mammoth electoral heft. In fact, its electorate is larger than the next seven large democracies combined, 858 million — Indonesia, the United States, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Russia, Mexico, and South Africa.

Seventy-two million new voters have been added to India’s electoral rolls since the last general election in 2019

Votes are cast electronically using what is known as electronic voting machines (EVMs) at over 1.2 million polling stations around the country spread over geography as diverse as the Himalayan mountains, remote islands, rain-soaked tribal areas and desert regions. Some 15 million personnel will supervise the voting process. They will travel by trains, helicopters, on horseback, and boats to fan out across the country.

Spread over 82 days from April 19 until June 1, with the results scheduled to be announced on June 4, the elections will decide whether Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) pull off a hattrick or the significantly diminished opposition makes a comeback.

The best that is being expected of the diffident opposition alliance is that they deliver a sobriety check to Prime Minister Modi and his BJP juggernaut.

Renewed vigour

In an atmosphere where even some of the most strident critics of Modi and the BJP say with a measure of resignation that his victory is a fait accompli and the only question is by how much, there are some discernible signs of undercurrents of renewed vigor among his challengers.

The main challenger is the Indian National Congress’ former president and main face Rahul Gandhi who exudes a measure of self-assurance that he believes results from insights into the people’s minds gained from his two cross-country marches.

On the one hand, Modi is projected to win 370 seats for his party on its own and over 400 along with its allies called the 38-member National Democratic Alliance (NDA). On the other hand, their opposition, the Indian National Developmental Inclusive Alliance (acronym INDIA) consisting of 26 opposition parties, hopes to unseat the prime minister.

Currently, the BJP has 303 seats in the 543-member parliament and 352 seats with its coalition partners.

The BJP’s only direct national rival, the Indian National Congress, once the unassailable political force for over five decades, has only 52 seats. Most reasonable political observers say that if the Congress manages to win even 100 seats on its own this time around, it should be considered an assertive comeback.

Considering that between the two opposing camps there are more than 60 political parties, a majority of them regional ones with limited political footprints, even this parliamentary election like most other previous ones is expected to be a complex and convoluted affair in terms of its party-specific expediencies.

Starting from now until May end, India will be in the grip of relentless electioneering expected to be marked by recriminations among rivals that would often degenerate into unvarnished name-calling despite the code of conduct being enforced by the Election Commission of India. Both Modi and Gandhi are known to take their gloves off—Gandhi more in response to Modi—as they both rally their allies. Speeches bordering on hate are expected notwithstanding Chief Election Commissioner Rajiv Kumar’s unambiguous warning.

Kumar challenged the media’s misgivings about bias within the Commission in favor of the ruling party while dealing with problematic speeches. At a news conference to announce the election schedules, he said, “Wherever there will be a case of violation against anyone, no matter how renowned the politician may be, we will take action against him or her.”

Issues on the table

There are several issues before the voters, including high unemployment, persistent inflation, a variety of protests topped off by the country’s politically consequential farmers and an economically distressed population of over 800 million Indians who receive food subsidies. While the government often highlights free ration to nearly 60 percent of the population as an accomplishment, economists argue that the very fact that such a vast number of people have to get by on free ration means the economy has not worked for a majority of people.

According to the Center for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE), a leading business information company, the unemployment rate among those aged 15 years and above was 8.7 percent in December 2023. That represented a decline of 0.2 percent over November 2023. Experts at the CMIE regard this level of unemployment as “fairly high”.

India’s elections have been called a “festival of democracy”. To maintain order, the Election Commission is expected to deploy 340,000 Central Armed Police Forces (CAPFs) personnel along with state police forces in the seven-phase Lok Sabha (lower house of parliament) elections and the assembly polls in four states. The politically volatile state of West Bengal will get 92,000 personnel, while 63,500 personnel will be deployed in the strategic border state of Jammu and Kashmir.

That a peaceful election in the world’s largest democracy is a huge organizational challenge, is a fact that needs no overstating.

(Mayank Chhaya is a veteran Indian journalist, author and filmmaker, based in Chicago, currently in India covering the elections)

A Sapan News syndicated feature.