Image Wikipedia

The Decline of Lollywood

By Dr Asif Javed

Williamsport, PA

“You do not want to go near a studio these days. Gone are the days when educated respectable people used to work there. Now, you find all kinds of ruffians, third-rate people there….I would not say that we do not have intelligentsia anymore. We do but they will not survive in the current atmosphere…our studios are worse than red-light areas…the era of Urdu movies was much better. Filmmakers were educated. The popularity of Punjabi movies has changed all that. It ushered in the era of indecent, vulgar crowd of filmmakers,” says Asif Jah who was once the foremost comedian of Lollywood.

It is hard to believe now but back in the 50s and 60s, several film directors came from respectable families and were highly educated: Anwar Kamal Pashawas the son of renowned writer Hakim Ahmad Shuja, was double MA and had come to movies having left a respectable job in the excise and taxation department; Masood Pervaiz, a nephew of Saadat Hasan Manto,was MA; WZ Ahmad’s older brother Maulana Salahuddin was the editor of Adabi Dunya while several of his siblings were in civil service; KhwajaKhurshid Anwar was a gold medalist from the Govt College, Lahore; his father was a barrister and one of his brothers was editor of Pakistan Times; Sibtain Fazli was also a college graduate.

The movie industry (sometimes called Lollywood) had to start almost from scratch in 1947 since most established studio owners and producers like Delsukh Pancholi and Roop K Shorey had left Lahore for Bombay. The riots in 1947 had heavily damaged several studios. The situation looked so hopeless that Mahboob and AR Kardar (who was

… the era of Urdu movies was much better. Filmmakers were educated… Masood Pervaiz, a nephew of Saadat Hasan Manto,was MA; WZ Ahmad’s older brother Maulana Salahuddin was the editor of Adabi Dunya while several of his siblings were in civil service; KhwajaKhurshid Anwar was a gold medalist from the Govt College, Lahore; his father was a barrister and one of his brothers was editor of Pakistan Times; Sibtain Fazli was also a college graduate

originally from Lahore) both went back to Bombay having visited Lahore. It is to the credit of Nazir and his wife Suran Lata who stuck around and made several hit movies including Lare and Phere. Nazir had left his own studio in Bombay where he had made several successful movies before partition. Nazir can rightfully claim to be the founding father of Lollywood.

AK Pasha should also get a lot of credit for making Lollywood stand on its feet. He made several successful movies in the 50s (Qatil, Intiqaam, DoAnsoo, among others) that competed favorably with the Indian ones. Unfortunately, his decline was as swift as his rise. Although he continued to direct movies into the 1980s, by the early 60s, his best days were already behind him. Some say that he had become arrogant and had allowed himself to be surrounded by a crowd of flatterers. Manto, who spared no one, wrote a scathing piece on Pasha back in the 50s titled Loudspeaker. Ali Sufyan Afaqi witnessed an episode of Pasha’s arrogance when Pasha snubbed one of the Fazli brothers while his cronies watched. Incidentally, Yawar Hayat, arguably one of the best directors of PTV back in the 80s and 90s was his nephew. Yawar Hayat once noted that Pasha had discouraged him to go into the movie direction. Yawar instead went into TV and made a name for himself. Pasha introduced several new faces in his movies. Asif Jah was one of his disciples and a great admirer.

Jall agitation in 1954 was a watershed moment for Lollywood. It led to a ban on the Indian movies in Pakistan. While it appeared an advantage to local movie production at the time, it proved detrimental in the long run. It gave a false sense of security to the filmmakers and removed the healthy competition so essential for a quality product.

The menace of plagiarism is not new; it had started way back in the 50s. It is hard to know exactly who started it but over the years, several film makers have been accused of this. This contemptable trait did not spare even GA Chishti who frankly admitted using two tunes from an Indian movie, under producer’s pressure, he once said. Chishti was among the senior musicians and had started work back in the early 40s. He had the distinction of using Noor Jahan’s voice when she was a child. He had taken Khayyam under his wings before partition. Khayyam later created a name for himself in Bollywood.

A strange early case of plagiarism was of Lakhte Jigar and Hamida. Both these movies were being made simultaneously and both were based on one story that had already been filmed in India. Naturally, both producers were in a hurry to release theirs before the competitor’s since it was the same story in both. Many producers used to fly to Kabul or London to watch an Indian movie and then ask the local writer to copy it. We are told that some Indian writers have done the same. But while Bollywood continues to thrive, Lollywood has been in the doldrums for years.

Looking back, it feels strange but there were several successful movie makers in India before the partition who, having moved to Pakistan, did very little work here. WZ Ahmad is a prime example: he had his own studio in Poona and had made several successful movies in India. Widely believed to be a talented movie maker, there were high expectations of him. But while he made several plans, he made only a handful of movies after partition. Most of his plans remained just plans. Afaqi writes that while a great planner, he was not good in the execution of his plans. What may also have contributed to his inertia was that he found an easy and steady source of income from a cinema that was allotted to him. Shaukat Hussain Rizwi’s case is similar: he had directed two successful movies before partition including Jugnoo (Dilip’s first hit). He was highly regarded but he too kept sitting in the Shahnoor studio that was allotted to him. He was later consumed by the unfortunate controversy with his ex-wife Noor Jahan that dragged on for years and destroyed the career of a brilliant cricketer, Nazar Mohammad. Shaukat Rizwi and WZ Ahmad’s inability to do for Lollywood what Mehboob and AR Kardar did in Bollywood remains a puzzle.

Noor Jahan was well-established in Bombay, both as an actress and a singer in 1947. Her decision to migrate to Pakistan came as a surprise to many since Rafi, Surraya, and Shamshad who were also from Lahore decided to stay in Bombay. She deservedly ranks among the very best singers. But her decision to continue acting hurt Lollywood. For several years, she would only sing for herself. That deprived music directors of her voice for movies that had other heroines. Only belatedly, did she realize her folly, gave up acting, and restricted herself to singing. Her contribution to Lollywood is second to none. But she too was arrogant. Over the years, she was dragged into several petty disputes with other singers (Roona Laila, Mussarat Nazir), actresses (Firdous) and musicians (KK Anwar, Master Abdullah, Nisar Bazmi). In later years, the quality of her voice suffered owing to singing poor-quality Punjabi songs.

M. Sadiq who had assisted AR Kardaar in India and had to his credit hits like Ratan, Chaudween Ka Chand, decided to return to Lahore in 1970. He was the native son and his arrival created a lot of excitement. As expected, he announced Baharo Phool Barsao. Wahid Murad and Rani were in the lead. Unfortunately, he died of a heart attack before completing his first movie in Pakistan. There were rumors that he was put under enormous stress by the unprofessional attitude of the lead pair. His death was a setback to the industry since he had vast experience in Bollywood. Nakhshab Jarchavi arrived from India in 1962. He had written songs for Zeenat (Ahin na bhareen, shikway na kiye) and Mahal. He had also directed a hit Zindagi Ya Toofan in India. There were high hopes of him. Unfortunately, both movies directed by him (Fanoos and Maikhana) flopped. He died at 42.

Master Ghulam Haider’s untimely death in 1953 was tragic for Lollywood. He was a huge talent. He is often credited with introducing Shamshad Begum and Lata. Riaz Shahid was a trailblazer: Zarqa (about Palestine) made after the 1967 Arab-Israeli war, was a superb effort for its time. He followed it with Gharnata (about Islamic Spain) and Yeh Aman (about Kashmir). His death in 1972 was most unfortunate. Talented Khalil Qaisar, also a quality filmmaker (Shaheed, Ajab Khan, Farangi), was murdered in 1966 in his home by an intruder. Both Riaz Shahid and Khalil Qaisar were relatively young and their deaths were a setback to Lollywood.

It is not that art movies have not been made in Pakistan.

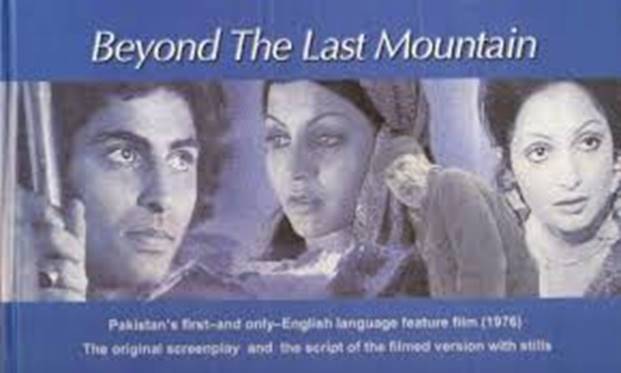

Javed Jabbar’s 1976 Musafar (the English version was called Beyond the Last Mountain) was a good movie that won praise from Raj Kapoor

There have been several attempts. Javed Jabbar’s 1976 Musafar (the English version was called Beyond the Last Mountain) was a good movie that won praise from Raj Kapoor. It turned out to be a miserable flop. NAFDEC’s own production Khak aur Khoon, another well-made movie, did not do well at the box office. Ahmad Bashir’s Nila Parbat written by Mumtaz Mufti met a similar fate. Pakistan was not going to find its Ingmar Bergman, Sita Jeet Ray or Shyam Banegal until Shoaib Mansoor’s arrived. But, having made a couple of excellent movies like Khuda Kay Liye and Bole, he has not done much recently. Ghazanfar Ali’s HaidarAli was a good movie too. It did not do good business. The only logical conclusion that one can draw here is that the audience has become too enamored of the gendasa culture and the same old love triangle-based stories. Our filmgoers must share some blame for the decline of Lollywood.

Looking back, it is obvious that the movies with violent themes had started way back in the early 70s. Bashira starring Sultan Rahi was the trendsetter. Just when Amitabh Bachan was beginning to play the angry young man in Bollywood, our own duo of Sultan Rahi and Mustafa Qureshi were getting started. And then it caught on. The number of Punjabi movies made from mid-70s to the 90s with violent themes and names like WehshiGujjar, Maula Jatt runs into hundreds. Luqman, a senior film director from the 50s and 60s, once observed with sadness that wherever one looks (in the 80s), the billboards publicizing movies have blood, rifles, and gandasa. The 80s brought another menace. It was the onslaught of Pashto-speaking artists in Lollywood. Nothing wrong with Pashto except that this group brought in vulgarity and nudity with it. It started with Dulhan Ek Raat Ki and then it took off. This scribe vaguely remembers the following news from the early 80s: Pathan artist Lahore ke nigarnamo par cha gaye. These artists were the likes of Badar Munir and Mussarat Shaheen who were as vulgar as they come. Hard to believe that KPK that had once produced Gul Hamid (a star in the era of silent movies in Lahore and Calcutta), Dilip Kumar, Prithwi Raj Kapoor, Sudhir, Qavi Khan, and Firdous Jamal had also produced the likes of Mussarat Shaheen. This may have been the final nail in the coffin of Lollywood for the middle class in general, and the women in particular, simply moved away from cinema. Who wanted to watch the rubbish with his family?

Lollywood never had its Dilip Kumar or Lawrence Olivier. These two names are being mentioned as the ones who were symbols of hard work and excellence in Bollywood and Hollywood respectively. Dilips’s attention to detail was legendary as was his work ethic. Compare that to his contemporary in Pakistan Santosh Kumar. Santosh was cut out to be a hero. He had several attributes that a hero requires: he was tall, very handsome, educated, and possessed that charm so essential for the leading man. He ruled Lollywood for years but could never rise above mediocrity as an actor. The reason: he hated hard work; he just took it easy; roles kept coming; he never made any serious attempt to excel in his craft like Dilip did. He was

Wahid Murad created a craze in the 60s that no one has since. But he refused to evolve with changing times – photo Youlin Magazine

notorious for being late at work. Wahid Murad created a craze in the 60s that no one has since. But he refused to evolve with changing times. As his movies started to flop one after the other, he developed depression. His death deprived Lollywood of arguably its best romantic hero and might have moved women away from movies. Sultan Rahi is another example: he was at the top in Punjabi movies for decades. He would often complain of being cast in monotonous roles but made no serious attempt to change that. He moved from one set to another to simply duplicate the same role year after year until he was gunned down near

Lollywood was not only a source of entertainment for the masses, it also created hundreds of jobs. Its decline had devastating consequences for those whose livelihoods depended on it. Will the good times ever return to Lollywood? Only time will tell

Gujranwala in 1996. He had the resources and the influence to ask for better roles but never did. We are told that Guinness book of records has his name as the one who worked in most movies. That may be so but his real legacy: hundreds of violent movies and gandasa culture.

When one thinks of what might have been, Zia Sarhadi’s name also comes to mind. In India, he had made quality movies like Ham Log and Foot Path with Dilip. He was a sought-after writer and director. He had leftist tendencies, and therefore was hounded by secret service in Pakistan. Disgusted, he moved abroad. He died in Spain. Zia-ul-Haq has a long list of actions that harmed Pakistan. Loss of Zia Sarhadi to Lollywood falls squarely on his shoulders. An attempt by govt. to register filmmakers in the 80s that was supposed to exclude those making poor quality movies came to nothing since every Tom, Dick, and Harry got registered.

Movie-making is serious business. Old-timers used to talk about the highly disciplined atmosphere of Bombay Talkies. Punctuality was expected and there was an emphasis on creativity. BombayTalkies had a well-stocked library. Its owners Humansu Rai and Devika Rani were both educated in the UK and had several foreigners on the staff. Sohrab Modi, who was the foremost filmmaker back in the 40s with hits like Pukar and Sikandar to his credit, was a practicing Parsi. He did not allow smoking or drinking in his studio. Compare that to what was happening in the Studios in Lahore in the 80s and 90s: gambling, use of alcohol and drugs was rampant; violence and sexual harassment was common. It was once reported that a heroine was seen running wildly in the lawn of a studio. She had just managed to escape an attempted gang rape. She was absolutely naked. Yousaf Khan was around and covered her with a chadar. She left the industry and moved abroad. Ijaz, a successful actor and producer, was found in possession of heroin at London’s Heathrow Airport. Moammar Rana, a popular hero until a few years ago, was manhandled by some ruffians in the studio a few years ago. A teary-eyed Rana later expressed his inability to work in the prevailing atmosphere.

Lollywood was not only a source of entertainment for the masses, it also created hundreds of jobs. Its decline had devastating consequences for those whose livelihoods depended on it. Just a few years ago, musician Ashiq Hussain’s son - also a musician - was seen working as a street vendor selling pakoras in Lahore to support his family including his elderly father. Will the good times ever return to Lollywood? Only time will tell.

References: Filmi Alaf Laila by Ali Sufyan Afaqi; Jahan-e-Fun by Zahoor Chaudhry; Asif Jah interview by Munir Ahmad Munir; Out of Date by Munir Ahmad Munir.

(The writer is a physician in Williamsport, PA, and may be reached at asifjaved@comcast.net )

Back to Pakistanlink Homepage