Book & Author

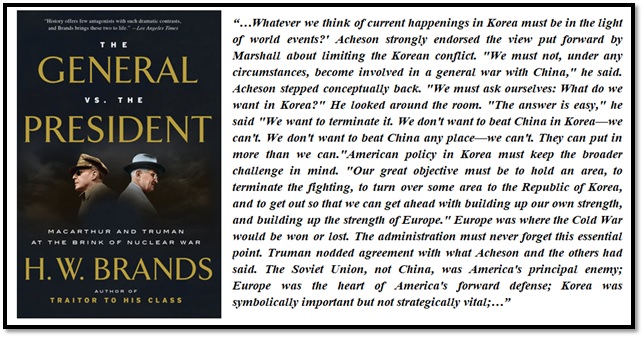

H.W. Brands: The General vs. the President — MacArthur and Truman at the Brink of Nuclear War

By Dr Ahmed S. Khan

In TheGeneral vs. the President — MacArthur and Truman at the Brink of Nuclear War, Professor H.W. Brands narrates the policy clash between General Douglas MacArthur and President Harry Truman during the Korean War. The narrative — with the help of numerous quotes — also illustrates how President Truman fired General MacArthur to uphold the supremacy of civilian rule in a democracy when General MacArthur tried to bypass President Truman by imposing his own decisions in the Korean conflict which could have triggered World War III.

As 1950 dawned, two larger-than-life American leaders — General Douglas MacArthur and President Harry Truman — were at the zenith of their careers. General MacArthur, a WWII war hero, and an ambitious general, had effectively implemented a policy of socio-economic and political reforms in Japan. A reluctant leader and an accidental President, Truman, had secured an upset victory in the last election. But within six months, the outbreak of the Korean conflict led to a series of events that placed the two leaders at loggerheads.

Harry S. Truman (1884 - 1972) was the 33 rd President of the United States. Only 82 days into his role as Vice President, meeting once President Roosevelt alone, receiving no briefing on the development of the atomic bomb and unfolding new challenges with the Soviet Union. On April 12, 1945 — when President Roosevelt passed away — Truman became President inheriting a plethora of problems to solve. President Truman told reporters: “I felt like the moon, the stars, and all the planets had fallen on me.”

Douglas MacArthur (1880 –1964) was an American military general and a war hero who served in WWI with distinction, played a key role during WWII by commanding the Southwest Pacific Theater, administrating postwar Japan during the Allied occupation, and leading UN forces in the Korean War for the first nine months.

The book, in addition to a prologue, has five parts: 1. Two Roads Up the Mountain, 2. Test of Nerve, 3. An Entirely New War, 4. The General vs. the President, and 5. Fade Away. The author has meticulously listed a plethora of sources and notes. He compares the personalities of the two leaders: MacArthur was a larger-than-life figure, revered in America after World War II, and a general who wanted to be president someday. In contrast, Truman was a plainspoken guy and a reluctant leader who accidentally became vice president and eventually the president.

Professor H. W. Brands holds the Jack S. Blanton Sr Chair in History at the University of Texas at Austin, where he obtained his PhD in history (1985). He was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in biography for The First American and Traitor to His Class. He has also authored several bestsellers which include Douglas MacArthur: American Warrior and Gandhi and Churchill, a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize.

A prolific writer, Professor Brands has authored more than thirty books which include, The Reckless Decade: America in the 1890s, The Age of Gold: The California Gold Rush and the New American Dream, Lone Star Nation: How a Ragged Army of Courageous Volunteers Won the Battle for Texas Independence, Andrew Jackson, The Man Who Saved the Nation: Ulysses Grant in War and Peace, and others.

Referring to events of December 1950, the author observes in the prologue: “The House of Commons was debating the optimal course of British foreign policy when the BBC brought word that Harry Truman was brandishing the atom bomb against China. This itself horrified the British lawmakers. The American president was the only person in history who had ordered the use of the monstrous weapon, and a man who had atom-bombed Japan might, without additional scruple, do the same to China. But there was a crucial new element, these five years after Hiroshima and Nagasaki, that made the prospect still more appalling. The Russians had the bomb, too, and were China’s allies. A nuclear war in 1950 would not be one-sided.”

The author further states: “And there was something else, something that pushed the alarm level in Britain far past that of any previous Cold War crisis. By Truman’s own statement, the decision on use of the atom bomb rested with the American field commander in Korea, Douglas MacArthur. Attlee and many others in Britain could think of no one more frightening than MacArthur to have control of the bomb. MacArthur was brilliant, brave, and imaginative—even his critics granted that. But the general had isolated himself so long in Asia, and surrounded himself with such sycophants, that he had lost all perspective. He suffered from an extreme version of the theater commander’s habit of thinking his own region the pivot of any conflict. During World War II MacArthur had behaved as though fascism would triumph or be defeated according to the outcome of battle in the Pacific; in the Cold War he contended that communism would win or lose depending on what happened in Asia. He had chafed at the communist victory in China’s civil war, now a year past. The outbreak of fighting in Korea five months ago had given him his chance to engage the communists, and the sudden entry of China into the conflict, just a week ago, had raised the stakes dramatically. MacArthur seemed to relish the opportunity to smash the communists, using whatever weapons were available. And now Truman was making the ultimate weapon available.”

Discussing the concerns of the British and French about a potential nuclear war, the author states: “The House of Commons burst into an uproar on hearing the word from Washington. Members of Attlee’s Labor party, already convinced that the Americans were reckless and MacArthur was a maniac, threatened a mutiny against their prime minister for his support of the American-led effort in Korea. To quell the uprising, Attlee announced that he would travel to America. He implied that he would talk sense and restraint into Truman. But he knew, and they knew, that this was more than he could guarantee. The mutiny hung fire, stemmed for the moment yet hardly vanquished. Britain’s alarm was broadly shared. None of the countries that had supported the United States in the defense of South Korea had bargained on the fighting there triggering World War III. The French distrusted MacArthur even more than the British did, and made no secret of the fact. The French National Assembly called for immediate negotiations to defuse the crisis in Korea.”

Commenting on the American fears about a potential nuclear war, the author notes: “Americans shuddered as well. ‘Is it World War III?’ asked TheNew York Times. The paper didn’t say yes, but it couldn’t say no. New Yorkers flooded the civil-defense offices of the city and state with demands to know where they should seek refuge when the Russian bombs began falling. The state director of civil defense tried to calm things but only made them worse when he said his office was operating ‘on the basis that an atomic or other attack could take place at any time.’ The response in other cities and states was much the same.”

Discussing President Truman’s outrage over the issues, the author observes: “If the world was alarmed, Harry Truman was livid. And he blamed Douglas MacArthur for getting him into this mess. In his five years as president, Truman had tolerated repeated slights and affronts from MacArthur: the general’s habit of making pronouncements on matters beyond his military responsibilities, his failure to return to America to brief the government on the US occupation of Japan, his campaigning for president in 1948 without bothering to resign his command. Truman had suppressed his anger, lest a public row between the president and the general threaten the precarious stability of the Far East. When MacArthur had refused to travel more than half a day from his headquarters in Tokyo to discuss the war in Korea, Truman had undertaken the long journey to Wake Island. There he heard the general state with utter self-assurance that the Chinese would never dare to enter the Korean fighting. If they did, they would be obliterated. A month later the Chinese entered the war. And they proceeded to manhandle MacArthur’s army. Truman was stunned and outraged. How could MacArthur not have seen this coming? Had his arrogance simply blinded him?”

Expounding on General MacArthur’s mega blunder and communist threat, the author states: “MacArthur’s horrendous misjudgment had put Truman in an impossible position. Since 1945 the president had been walking a knife-edge of decision between appeasement and war: between yielding to communist pressure and tipping the planet into a new world conflict. In 1946 a stern warning had sufficed to keep the Kremlin from grabbing Iran. In 1947 a stronger dose of American power, in the form of military aid to Greece and Turkey, had preserved the Balkans from a communist takeover. A massive airlift in 1948 had kept Berlin free. The North Atlantic Treaty of 1949 made clear to Moscow that an attack on any of America’s allies would be met with the full force of America’s arsenal. Billions of dollars of Marshall Plan money continued to pour into Europe to bolster democracy there.”

Commenting further on the communist threat, the author notes: “The North Korean attack on South Korea in June 1950 proved that the communists never rested. Truman had responded with measured force, enough to secure South Korea yet not so much as to bring the Soviets into the conflict. But then MacArthur’s recklessness had provoked the Chinese to enter the fight. The Soviets, linked to the Chinese by a military pact, and as opportunistic as ever, wouldn’t miss a chance to jump the United States where America’s alliances were most vulnerable, should the Asian war escalate further. And further escalation was exactly what MacArthur was demanding.”

Explaining how MacArthur’s blunder narrowed Truman’s options, the author observes: “The knife-edge that Truman had been walking suddenly terminated above an abyss. He couldn’t go forward without risking a nuclear World War III. He couldn’t retreat without undermining the morale of all who looked to America for leadership of the forces resisting communism. MacArthur had drastically narrowed the president’s options, and the general had the gall to complain that his hands were being tied…This was even bigger news. MacArthur’s finger was on the nuclear trigger…. The clarification didn’t alleviate the alarm, for it didn’t materially revise Truman’s own words. The president was considering the use of the bomb, and MacArthur would determine the time and place.”

Reflecting on the pressures President Truman felt due to MacArthur’s fiasco, the author states: “Truman cursed his bad luck, and he cursed MacArthur. The last thing he wanted was to have to use atomic weapons. He claimed not to have lost sleep over the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but no one takes the deaths of a hundred thousand civilians lightly. He hoped not to have to make such a decision again. And this time the consequences would be far more terrible. World War II had ended with atomic bombings; World War III would begin with them. But he couldn’t back down. The Chinese were watching. The Russians were watching. Americans were watching. The world was watching. Now Attlee was coming. Truman hated being on the spot like this: having to explain that he wasn’t intending to start another world war, yet having to avoid seeming fearful or reluctant to oppose the communists.”

The General vs. the President — MacArthur and Truman at the Brink of Nuclear War by H. W. Brands is a well-researched, well-written comparative study of two American leaders — President Truman and General MacArthur — who were at loggerheads over decision-making during the Korean War crisis.

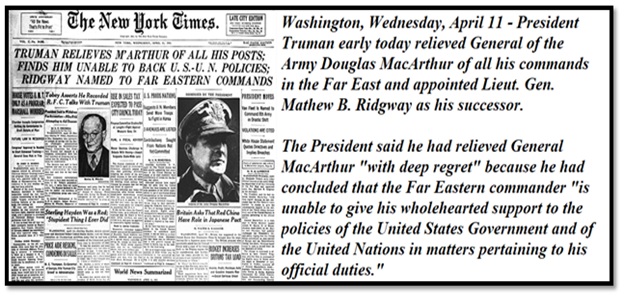

Professor Brands narrates the most significant and dramatic events in modern American history; President Truman and General MacArthur pondering over the issues that would define the course of the Cold War, the use of atomic weapons, and eventually President Truman establishing the supremacy of civilian chain of command over military by firing General MacArthur from command of UN forces in Korea.

The author illustrates how Truman did not yield to communist aggression in Korea, and did not panic to let him be stamped into World War III, as MacArthur and others desired. During the last three decades —the collapse of the Soviet Union and the Chinese abandonment of communism in all but name — vouch for the success of Truman’s visionary policies to contain communism and to establish the supremacy of civilian rule.

The book has some flaws too. Professor Brands sometimes makes inaccurate statements about the meetings of key historical figures like John Snyder, Clement Attlee, and others. Too much use of quotes from newspapers attenuates the scholarly tone. Despite these flaws, overall Professor Brands does a fine job of presenting the beginning of the Korean conflict and the personality clash between two larger-than-life figures — General MacArthur and President Truman. The book is essential reading for all students of history, political science, and international affairs.

(Dr Ahmed S. Khan — dr.a.s.khan@ieee.org— is a Fulbright Specialist Scholar)