Book & Author

Professor Dr Muhammad Yunus: Banker to the Poor

By Dr Ahmed S. Khan

"Give a man a fish and you feed him for a day. Teach a man to fish and you feed him for a lifetime."— Chinese proverb

The recent bloody revolution in Bangladesh has led to the establishment of an interim government headed by Nobel Peace Prize laureate Professor Dr Muhammad Yunus. For the past fifteen years — he was politically victimized by Sheikh Hasina — the Bangladeshi prime minister who saw him as a potential political leader and an opponent. Dr Yunus has described the revolution as yielding the second liberation, but in reality, it’s the third liberation for the Muslims of Bengal: First, on August 14, 1947, when they gained independence from the British in the creation of Pakistan; second, on December 16, 1971, creation of Bangladesh as a result of the Fall of Dhaka (when Pakistan’s power-drunken Generals refused to hand over power to the Awami League which had won a clear majority in the 1970 Elections); and third, on August 5, 2024, liberation from Indian colonial rule via Sheikh Hasina.

The student-led revolution has ended the brutal and dictatorial rule of Sheikh Hasina. During the past two decades, she suppressed freedom of speech, jailed, abducted, brutalized and murdered her opponents with the help of her security forces which had a heavy presence of Indian proxies — opposing political parties as well as ordinary people lived in extreme fear!

Sheikh Hasina served as prime minister (June 1996 – July 2001) and (January 2009 – August 2024). Her reign of terror ended on August 5, 2024 when her military chief, a close relative, informed her that a crowd of over a million people was converging towards her residence angry at the killing of hundreds of protestors —so to save her life she must escape. She initially resisted but when she was told by the army chief that things were out of control and she had only 45 minutes to flee. Finally, after talking to her sister and son — she agreed and fled to India on a military plane.

The catalyst for student-led protests was the quota system in which thirty percent of jobs were reserved for the freedom fighters (veterans known as mukhtijodha) of the civil war of 1971. “Why do they have so much resentment towards freedom fighters?” Sheikh Hasina said in a public statement. “If the grandchildren of the freedom fighters don’t get quota benefits, should the grandchildren of Razakars get the benefit?” Razakars (volunteers/collaborators) refer to people who sided with the Pakistani forces in the 1971 civil war. In response to her comments students all over Bangladesh, mocked her by chanting the slogan: Ami Ke? Tumi Ke? Razakar, Razakar, Ke Boleche, Ke Bolecha, Shairachar, Shairachar (Who am I, Who are you, Razakar, Razakar, who said, who said, autocrat, autocrat).

In June 2024, when she provided India with a railway corridor to its northeastern part through Bangladesh territory, critics accused her of selling out to India and making Bangladesh a colony of India. With her removal from politics, people all over Bangladesh are looking forward to a new dawn of freedom in the country and the decolonization of Bangladesh from Indian domination.

Dr Yunus faces a plethora of issues and challenges: How to restore law and order? How to unite the country? How to tame pro-Indian anti-liberation forces? How to revive the economy? How to free the Bangladesh market from Indian control? How to stop the flow of capital from Bangladesh to India? How to deport a million illegal Indians working in Bangladesh? How to create jobs for millions of youth? How to set up foundations for independent judicial and political institutions? And many other political and socioeconomic challenges.

Professor Dr Muhammad Yunus does not believe in charity or elaborate government spending programs to eliminate poverty; rather, he puts his trust in empowering individuals by providing them the privilege of microcredit, that is, loaning them money at very low interest rate. In his words “…charity, like love, can be prison.”

Embracing the principle of “teaching a man to fish,” Professor Yunus realized the importance of offering micro credit to the poor and hence transformed the lives of millions of people in Bangladesh and around the world. He believes that the right to credit should be recognized as a fundamental human right because credit is the last hope left to those faced with absolute poverty.

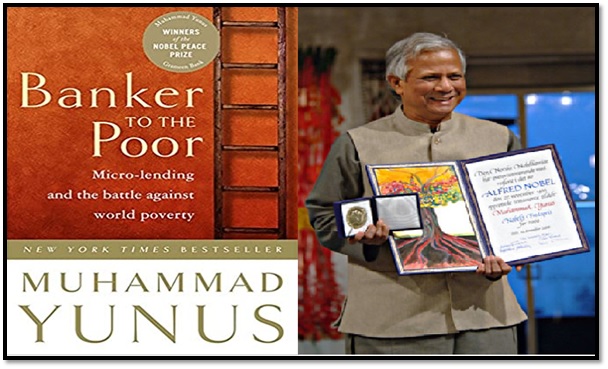

The Nobel Peace Prize for 2006 was awarded to Muhammad Yunus and Grameen Bank for their efforts to create economic and social development from below. The Nobel Prize committee observed that “lasting peace cannot be achieved unless large population groups find ways in which to break out of poverty. Microcredit is one such means. Development from below also serves to advance democracy and human rights.”

For the last three decades, Dr Yunus has won accolades from many world leaders for his work to end poverty. Former US president Jimmy Carter has said: “By giving poor people the power to help themselves, Dr Yunus has offered them something far more valuable than a plate of food-security in its most fundamental form.” Former US first lady, Hilary Clinton said, “I only wish every nation shared Dr Yunus’s and the Grameen Bank’s appreciation of the vital role that girls and women play in the economic, social, and political life of our societies.”

Banker to the Poor is the autobiography of Professor Dr Muhammad Yunus, founder of the Grameen Bank, the person and the institution who have transformed the theories of dealing with the complex societal problem of poverty by offering the simple and innovative solution of microcredit. Dr Yunus’s autobiographical account, in fact, is an appeal for a universal action: Nations should concentrate on promoting the will to survive and the courage to build the very first and the most essential element of the economic cycle — Man.

Eloquently, forcefully, and passionately, Dr Yunus shows the reader how, by extending micro-credit to the poor, poverty can be eliminated. The book is a fascinating read, a time-travel through the past six decades, telling the tale of a dream of ending poverty from its emergence to its fulfillment.

His narrative is simple in style but full of insights. He provides a self-portrait of his life’s journey, from growing up at 20 Boxirhat Road, Chittagong to going to the United States for graduate studies; from coming back to Chittagong and finding the anomalies between the elegant theories of economics and the dismal state of poverty in Jobra village to the creation of the experiment of offering micro-credit to the poor; from the establishment of Grameen Bank in Bangladesh to replicating Grameen principle internationally; and from holding the first micro-credit summit in Washington DC to his vision of a poverty-free world.

Dr Yunus reminisces about his growing up on 20 Boxirhat Road, in the heart of the old business district of Chittagong, and pays respect and homage to his parents and teachers. About his father, he states: “My father was a devout Muslim all his life, and made three pilgrimages to Mecca. His square tortoise-shell glasses and his white beard made him look like an intellectual, but he was never a bookworm. With his large family and his successful business, he had no time or much inclination to look over our lessons. He usually dressed all in white, white slippers, white paijama pants, a white tunic, and a white prayer cap. He divided his time between his work, his prayers, and his family life.”

Remembering his mother, who taught young Yunus the traits of discipline, love, charity, the importance of compassion, and kindness, he notes: “My mother, Sofia Khatun, was a strong and decisive woman. She was the disciplinarian of the family, and once she bit her lower lip and decided something, we knew nothing would budge her. She wanted us all to be as methodical as her. She was full of compassion and kindness, and probably the strongest influence on me. She always had money put away for any poor relations who visited us from distant villages. It was she, through her concern for the poor and the disadvantaged, who helped me discover my destiny, and she who most shaped my personality…my mother did something else which fascinated me. She worked on some of the jewelry to be sold in our shop. She often gave a final touch to earrings and necklaces by adding a bit of velvet or woolen pompoms to the end of the ribbon, or by attaching braided colored strands. Amazed, I watched her long thin hands work and make truly beautiful ornaments. It was this money she earned on the side that she gave away to the neediest relatives, friends, or neighbors who came to her for help.”

Recalling his extracurricular activities and a teacher who electrified his imagination, Dr Yunus observes: “I especially recall a train trip across India on the way to the first Pakistan National Boy Scout Jamboree in 1953, when we stopped to visit important historical sites and relics. The journey became a time-travel through our history, almost a pilgrimage to meet our own true selves. Most of the time we sang and played, but standing in front of the Taj Mahal in Agra, I caught our assistant headmaster, Quazi Sirajul Huq, a man loved by his students, weeping silently. The tears were not for the monument, nor for the famous lovers who were buried there, nor for the poetry etched on the monument in white marble, no. He said he was weeping for our destiny, the burden of history that we were carrying, and not knowing what to do with it. I was only thirteen, but I was infected by his passionate imagination. Quazi Sahib became my friend, philosopher and guide for life…Quazi Sahib electrified my imagination. He had a sublime moral influence on all of us in his care. He taught us always to aim high, and channeled our passions and restlessness. He did not do this through preaching but through deeds and heart-to-heart communication which had a lifelong effect on me.”

Reflecting on his campus years (1965-72) at Vanderbilt University in the US, Dr Yunus admires his mentor Professor Georgescu-Roegen: “He was an old-fashioned European teacher who kept his distance. The books he wrote were much too erudite, impossible to understand, but he spoke clearly and concisely. He was a mathematician, a philosopher and had been finance minister of Romania until 1948, when he had to leave and seek political asylum in the United States. He spoke so beautifully that, taken word for word, his classes were a work of art. I studied advanced statistics with him as well as economic theory and Marxism... As his teaching assistant, I learned to respect precise models which showed me how certain concrete plans can help us understand and construct the future. I also learned that things are never as complicated as we imagine them to be. It is only our arrogance which seeks to find complicated answers to simple problems.”

After earning a PhD from Vanderbilt University, he returned to Chittagong and discovered the wide gap that existed between the elegant theories of economics and real life. He observes: “The year 1974 was the year which shook me to the core of my being. Bangladesh fell into the grips of a famine…I used to get excited teaching my students how economics theories provided answers to economic problems of all types. I got carried away by the beauty and elegance of these theories. Now all of a sudden I started having an empty feeling. What good were all these elegant theories when people died of starvation on pavements and on doorsteps?”

Professor Yunus started his poverty relief work in Jobra village located in the vicinity of the University of Chittagong. Regarding Jobra village’s close proximity to the University, he reveals an interesting story: “I was lucky that Jobra was close to the campus. Field Marshal Ayub Khan, the then President of Pakistan, had taken power in a military coup in 1958 and ruled until 1969 as a military dictator; because of his strong distaste for students, whom he considered troublemakers, he decided that all universities founded during his rule had to be located away from urban areas so that students would not be able to disrupt the centers of population with their political agitation…I decided I would become a student all over again, and Jobra would be my university. The people of Jobra would be my teachers.”

Professor Yunus, with the help of his colleagues and students, started to visit families in the Jobra village to collect facts about poverty and to offer help to the people. He recounts his meeting with Sufia Begum, a village resident who borrowed money to make bamboo stools to earn a living to feed her family. He discovered that Sofia Begum was so poor that she had to borrow the equivalent of 22 US cents to buy bamboo. After paying her debt at a very high finance charge, she was left with only 2 cents of profit to take care of her daily family needs. His work in Jobra village further revealed that 42 families in the village were living in poverty because they did not have $27 to sustain themselves. He was distressed by what he discovered. He notes: “My God, my God, all this misery in all these forty-two families, all because of the lack of $27! I exclaimed… My mind wouldn’t let this problem lie. I wanted to be of help to these forty-two able-bodied, hard-working people…Usually, when my head touches the pillow, I fall asleep within seconds, but that night I lay in bed feeling ashamed that I was part of a society which could not provide $27 to forty-two able-bodied, hard-working skilled persons to make a living for themselves…My thinking up until then had been ad hoc and emotional. I needed to create an institutional response on which they could rely.” Professor Yunus gave $27 out of his pockets to the forty-two families, and thus Jobra became the test bed for his micro-credit experiment to take people out of the shackles of poverty, and the rest is history.

Dr Yunus started his experimental microcredit enterprise in 1977 and by 1983 the Grameen Bank was officially established. The Grameen Bank started to provide credit to the poorest of the poor in rural Bangladesh without any collateral. The credit proved to be a cost-effective weapon to eliminate poverty by acting as a catalyst for improving socio-economic conditions.

In 1996, commenting on the success of the microcredit model, James Wolfenshohn, president of the World Bank, acknowledged, “Micro-credit programs have brought the vibrancy of the market economy to the poorest villages and people of the world. This business approach to the alleviation of poverty has allowed millions of individuals to work their way out of poverty with dignity.” It is important to observe that Dr Yunus achieved this success without accepting any help from international donor agencies or by compromising his principles.

Reflecting on the philosophy of Grameen, Dr Yunus states, “Grameen is committed to social objective --- eliminating poverty, providing education, health-care employment opportunities, achieving gender equality by promoting the empowerment of women, ensuring the well-being of the elderly. Grameen dreams about a poverty-free, dole-free world.”

Commenting on the idea of the clash of civilizations, Dr Yunus observes, “Some of the West’s great geostrategists and thinkers see the world locked in future cultural struggles, such as Christianity versus Islam. They seem to think it is inevitable and are quite pessimistic because of the militancy of certain extremist regimes. We at the Grameen do not look at the world this way. We make loans to Muslim, Hindu, Christian, and Buddhist women alike…there is no reason for religious or cultural wars if the poorest can, through their own self-help, their own micro-capital, develop and become independent, active, thinking, and creative human beings. Let’s hope that the West, champion of capitalism, will see and learn the lessons we have learned here in Bangladesh.”

On poverty, the missing issue in Economics, Dr Yunus poses a question to economists: “Why have economists been silent when banks insisted on the ridiculous and extremely harmful generalization that the poor are not creditworthy? Nobody can provide a convincing answer. Because of this silence and indifference, financial institutions could impose financial apartheid and get away with it.”

Dr Yunus observes that economics textbooks have no use for the word ‘self-employment,’ and further states: “That is what has created trouble in real life; just because our textbooks banished this word, policy-makers banished it from their minds too…In many Third World countries, an overwhelming majority of people make a living through self-employment. Not knowing where to fit this phenomenon into their analytical framework, economists lumped it into a catch-all category called the ‘informal sector.’ Because they did not have the analytical tools to cope with the situation, they concluded that it was not a sensible one: as soon as these countries could eliminate this informal sector, the better off they would be. What a shame!”

In the final section of the book, Dr Yunus poses a question: “Can we really create a poverty-free world? A world without third-class or fourth-class citizens, a world without a hungry, liberated barefoot underclass?” And then, he answers: “Yes, we can, in the same way we can create ‘sovereign’ states, or ‘democratic’ political systems, or ‘free market economies’. A poverty-free world would not be perfect, but it would be the best approximation of the ideal. We have created a slavery-free world, a polio-free world, an apartheid-free world. Creating a poverty-free world would be greater than all these accomplishments, while at the same time reinforcing them. This would be a world that we could all be proud to live in.”

The book is co-authored by Alan Jolis, an American journalist who has authored Love and Terror, Speak Sunlight, and other children’s novels. He has also been a contributor to Vogue, Architectural Digest, the Wall Street Journal, the International Herald Tribune and other publications.

Dr Yunus’s autobiographical account is a work of historical importance. For the first time in history, an economist has tried to address the flaws of economic theory by devising and implementing a microcredit-based model to eliminate poverty. It is a brilliant book, a must-read for all those who care and have passion for ending the sufferings of fellow human beings.

As Rumi said, “Try being poor for a day or two and find in poverty double riches.” Indeed, Dr Yunus has dedicated his life to championing the problems of the poor and has found his riches in the form of a Nobel Prize.

In Banker to the Poor, Dr Yunus has documented the development and implementation of an effective model for eliminating poverty. Now the onus is on the world leaders to formulate policies to achieve a poverty-free world. Hopefully, as head of an interim government, Dr Yunus will lead people to make Bangladesh a true democratic and economically prosperous country!

(Dr Ahmed S. Khan – dr.a.s.khan@ieee.org – is a Fulbright Specialist Scholar.)

Back to Pakistanlink Homepage