Invasion Cascade: Ants, Lions, Zebras and Buffalo

By Dr Khalid Siddiqui

Ohio

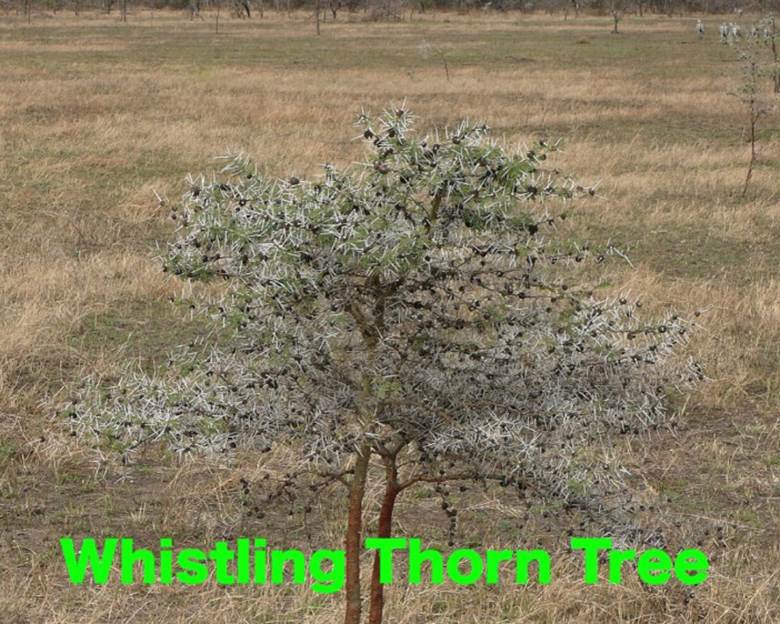

Across tens of thousands of square miles of East Africa, a type of acacia called the Whistling Thorn tree grows as a dominant plant species, accounting for 70% to 99% of woody plant mass in that area. In addition to regular spiny 7-cm long thorns, the tree also produces swollen hollow thorns called domatia. Glands near the base of the tree’s leaves secrete a carbohydrate-rich nectar called nectaris.

Acacia ants (C. mimosae) use these domatia as shelter and nesting place and feed on nectaris. About 52% of these trees are occupied by acacia ants. The ants are aggressive defenders of these trees from the herbivores like elephants and giraffes. They bite the animals and swarm up the trunks of the African elephants who try to browse on the leaves of the trees. These herbivores have learned it over the years, and leave the Whistling thorn trees, that are infested with these ants, alone. However, the African Black Rhinoceros can easily browse on the leaves over the lower branches. The shape of their mouth and lips makes it harder for the ants to sting. The tree, with its leaves mostly intact, provides an ideal cover for the lions who can ambush the unsuspecting zebras who happen to pass by. The lions prefer not to chase the zebras because they are fast runners, and their kicks could be harmful. This arrangement has been working perfectly for the trees, ants, and lions for centuries. However, something happened around 24 years ago that disturbed this balance.

At some point in the early 2000s, big-headed ants (P. megacephala) appeared in the plains of Laikipia, Kenya. They, most probably, came from the island of Mauritius in a banana shipment. (This migration is quite rare because most of the bugs relocate from mainland Africa to the islands.) Anyway, the big-headed ants acted very aggressively. They killed the native acacia ants, and ate their eggs, thereby destroying their colonies. Thus, they have been slowly replacing the acacia ants on the Whistling Thorn trees. More importantly, the big-headed ants are friendly towards the herbivores and don’t defend the tree against them. The elephants and giraffes have figured this out. As a result, the trees invaded by big-headed ants have been denuded of the leaves by the herbivores with virtual impunity. It is estimated that the elephants browse and break trees five to seven times more often in the invaded areas. Consequently, in these more open landscapes, the zebras can see the lions coming and have time to escape. The Rhinos also suffer, to some extent, because more and more trees are being broken by the elephants now.

A study was conducted by a wildlife ecologist, Prof. Jacob Goheen ( Department of Zoology and Physiology), and his team at the University of Wyoming. I know Dr Goheen very well. His study found that 16% of the Whistling Acacia trees have already been taken over by the big-headed ants. One would have expected the lion population, because of the difficulty in hunting the zebras, to have declined in that area, but it didn’t. It was found that the lions have, instead, switched to hunting buffalo. It’s not easy for lions to kill the buffalo. It requires a lot of energy compared to hunting zebras, besides buffaloes can kill lions. But, at the same time, heavier and slower buffalo are easier to catch than the swift zebras. Still, only the pride of lions can bring down a buffalo while a lonely lion could kill a zebra. The study showed that in the seven-year period, as the big-headed ants have spread, the zebra killing dropped from 67% to 42%, and the buffalo killing rose from 0% to 42%. It’s unclear whether this dietary shift is sustainable. The rhinos, however, did fine because they moved on to the other trees. And, anyway, they eat grass mainly.

The big-headed ant invasion has triggered a chain of consequences, called the ‘Invasion cascade’, where a predator switches to another prey as a result of invasion by another species (in this case the ant invasion helping zebras at the expense of buffalos). So, the disruption of an ant–plant mutualism modified a predator–prey interaction by restructuring the physical habitat.

Experts wonder whether the buffalo numbers will decline if lions continue to hunt them, or whether the plant communities and wildfire patterns will change as grazing zebras face less hunting pressure.

Most certainly, the humans were responsible for the invasion of the big-headed ants. Further studies are needed to assess the long-term impact of its spread which currently clocks at about 50 meters per year.

Blue-footed boobies nest on the ground in the N. Seymour island which is a part of Galapagos Islands. Here few little fire ants had arrived with the food brought in by a tourist. The ants proliferated and started attacking the defenseless blue-footed booby chicks on the ground. Many chicks died. It took the authorities quite some time to get rid of the ants even though N. Seymour is a very small island. It wouldn’t be easy to get rid of big-headed ants from East Africa.

Should efforts be made to stem their advance before it is too late? Dr Goheen told me that a plan to spray over the underground nests of the big-headed ants is in place, but is on hold as of now. It is argued that since the lion population has not declined, it is better to wait a little bit longer. Moreover, spraying the area is expensive and it may damage the local vegetation also.

(The photographs with a red dot have been provided by Dr Goheen. The photograph of the blue-footed boobies and the chick was taken by me when I visited the Galapagos Islands in 1997. The other photographs are from the Internet.)