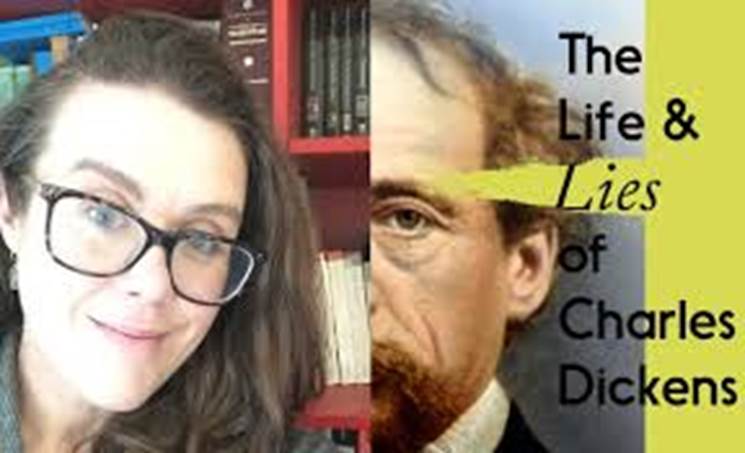

Fact and fiction: Dickens in 1860 - Hulton Archive/Getty Images

The Life and Lies of Charles Dickens Review — A Complicated Man

By John Carey

Helena Kelly’s book presents a fresh view of Dickens, just as her previous book, Jane Austen, the Secret Radical, did for Austen. It opens with Dickens performing conjuring tricks to amuse a friend’s children, aided by his close friend, the Victorian biographer John Forster. This could stand as an emblem for the whole book, as Forster’s three-volume The Life of Charles Dickens incorporates, as Kelly sees it, many of Dickens’s lies about himself.

Forster’s account, published just 18 months after Dickens’s death, still influences how we think about the author today. It was he who first told us the story of Dickens’s childhood: Dickens’s father was imprisoned for debt, and the rest of the family took up residence with him, as was usual. But young Dickens was left to fend for himself. Scarcely 12, he earned his living by pasting labels onto jars of boot polish in a Thames-side factory — Forster wrote that this experience was the inspiration for David Copperfield.

Forster depicts the blacking factory as a fearful place, with “old grey rats swarming down in the cellars”. Dickens would breakfast on a penny loaf and a penny bottle of milk, lunch on stale pastries, sold cheap, and eat bread and cheese for his supper. Or so he says. Might he have been an apprentice of the factory owner instead?

Kelly questions everything, even her own arguments. For instance, Forster, bound by Dickens’s own silence, made little mention of a sister, Harriet, who was disabled. Most biographers suggest she died as a baby. Not so Kelly, who argues Harriet might have lived to the age of nine, and been the inspiration for Tiny Tim.

Shortly after his 15th birthday Dickens became a clerk for a law firm and by 1829, he was working for a journal of parliamentary reporting. Kelly quotes Dickens’s account of what being a journalist in those days entailed: “Writing on the palm of my hand, by the light of a dark lantern, in a post-chaise and four, galloping through a wild country all through the dead of night.”

His first love was Maria Beadnell, a banker’s daughter, and out of Dickens’s class. Her family bundled her off to a finishing school in Paris, and on the rebound Dickens married Catherine Hogarth. She produced their first child soon after the wedding and went on producing them at an alarming rate. Dickens talked about his growing family jokily, as if it had nothing to do with him. But Kelly persistently and usefully reminds us of the woman’s point of view.

For example, Dickens writes to Catherine, who has just given birth to their ninth child, Dora: “I have still Dora to kill — I mean the Copperfield Dora.” Kelly comments: “How baby Dora’s mother felt reading this, or having it read to her — blood seeping from between her legs, milk starting to weep from her breasts — we can only imagine.”

Catherine accompanied him on his visit to America, and his letters to friends show the first signs of his impatience with her — joking about her “propensity” for tripping when climbing into boats. He started sleeping separately from Catherine, and made it surprisingly public. He arranged for “a small iron bedstead” to be delivered to his London house and put into his dressing room, and for the doorway between Catherine’s and his to be blocked up.

He was able to do without Catherine, his wife of 22 years who had borne him 15 children, because he had acquired a new, younger mistress. She was called Ellen Ternan and she came from an acting family. It has long been thought Dickens and Ternan had a son who was assumed to have died young. Kelly argues they did indeed have a son, but that he did not die as a child. She discovers a “decent candidate”, Howard Cleveland, who entered the navy and lived until 1942, making him 80. Dickensians will doubtless continue to argue over it.

Festivals.com

Dickens’s antisemitism is also brought under the microscope. Kelly studies his Jewish characters, such as Oliver Twist’s Fagin, who is introduced as “a very old shriveled Jew” with a “villainous-looking and repulsive face”. Kelly notes that Dickens refers to Fagin as “the Jew” over 100 times in the novel. But she also uncovers evidence that the author may have had an uncle, Matthew Lamert, with Jewish ancestry. And she points out positive Jewish characters in other books, such as friendly Mr Riah in Our Mutual Friend. “There is no way, though, that Dickens’s antisemitism should be minimized,” she concludes.

Ultimately, is Kelly’s case persuasive? Not for me. To say that Dickens lied is only to say that he was a writer of fiction. His portrayal of himself as an abandoned child who made a life for himself is compelling — it’s why we still read Great Expectations.

Some facts are indisputable. Charles Dickens died on June 9, 1870, and was laid to rest in Westminster Abbey. After the funeral, the grave was left open, and Londoners were invited to pay their respects to the greatest novelist of the age. Some dropped small posies, or buttonholes, on top of the coffin. By the end of the day the grave was full of flowers.

The Life and Lies of Charles Dickens by Helena Kelly (Icon £25). To order a copy go to timesbookshop.co.uk . Free UK standard P&P on orders over £25. Special discount available for Times+ members. – The Times