X. com

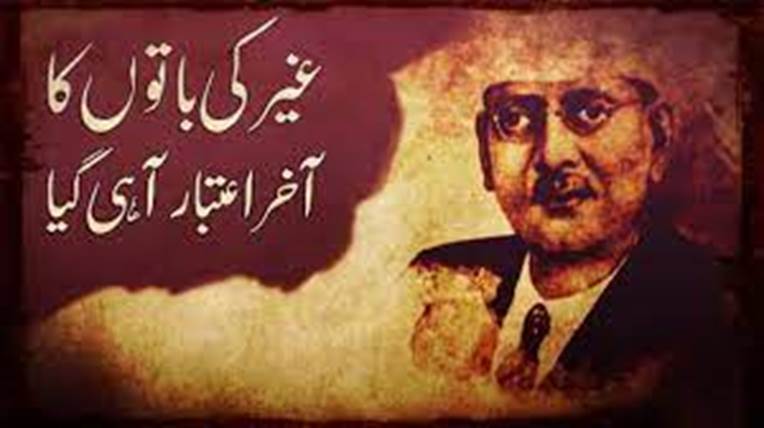

Agha Hasher Kashmiri – The Forgotten Shakespeare of Urdu

By Dr Asif Javed

Williamsport, PA

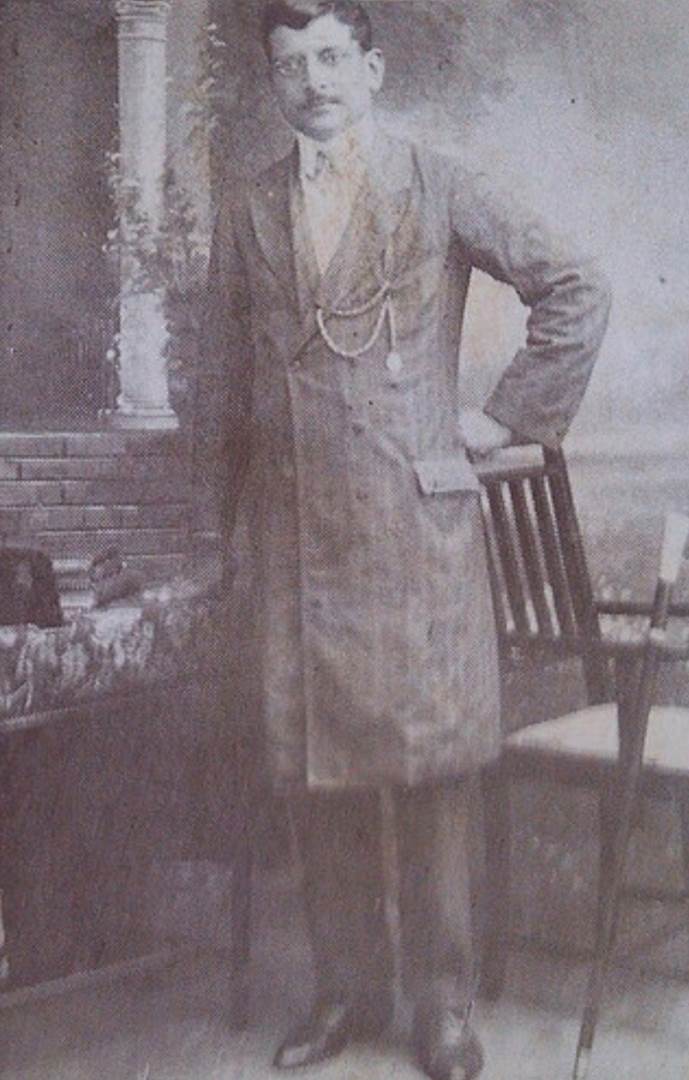

Manto and Agha Hasher met only twice: once in Amritsar and later in Lahore. Manto did not like Hasher’s dress, nor did he like his demeanor. In Manto’s sketch, Hasher comes across as a strange-looking man: loud, haughty, cross-eyed, who uses foul language.

The second meeting was at a bookshop in Lahore. Manto was accompanied by his mentor Bari. Manto’s keen eye did notice the tremors in Hasher’s hands. Hasher bought several books, some at Bari’s suggestion. A brief conversation about Victor Hugo and French literature followed. True to style, Hasher made sure to tell Bari and Manto that he had just been to the bank and had been given the privilege of cashing his check after hours and that the bank manager had given him brand-new currency notes. Manto spared no one with his razor-sharp pen and his description of Agha Hasher naturally is less than flattering.

A slightly different Agha Hasher begins to emerge when one reads the account of those who knew the great dramatist more. Ashiq Batalwi met Hasher several times in Lahore and noted:

I was not keen to meet Hasher. I had heard stories of his vanity and snobbery. Persuaded by my friend Mansoor Ahmad, the editor of Adabi Dunya, who was a great admirer of Hasher’s intelligence and sharp wit, I reluctantly went. After that, I visited Hasher often...Hasher’s talk was most entertaining and sometimes would surprise listeners. He used obscenities at times...In those days, there was a woman with him who was essentially in control of all aspects of his life. I am referring to the famous singer (Manto calls her courtesan) from Amritsar, Mukhtar Begum. Mukhtar was no raving beauty (this had been Manto’s observation too). But she had an unusual elegance and pleasing demeanor that had captivated Hasher who was madly in love with her. They had met at Calcutta where she had worked in a couple of movies written by him…Hasher had a strange way of living. He was unable to hold on to money. He earned thousands (millions in today’s currency) and would spend it all before no time. Everything was bought on credit in his house. After a big payday, all arrears were paid off...Once I asked whether he approved of being called Indian Shakespeare. Hasher said, “Yes, I do. And why not?” Having seen a look of surprise on my face, he then said, “Flattery is soothing to one's soul. It makes me happy."

Hasher, it seems, had taken the undesirable trait of self-admiration to another level and frankly admitted it. On another occasion, Batalwi asked Hasher about the recitation of his poem Shukriya Europe in the annual meeting of Anjuman-e-Himayat-e-Islam. There had been rumors that Hasher’s presence at the meeting had generated controversy. This is what Hasher told Batalwi:

Yes, some were unhappy since they did not want a drama writer (Hasher used the terms bhand and mirasi) like myself to be on the stage that had been graced by Hali, Shibli, and Nazir Ahmad. After I had recited Shukriya Europe to great applause, I looked at the front row where the so-called nobility was sitting. I said to them, “My line is different from yours. I have deliberately stayed away from yours, otherwise, you would not be where you are, and these chairs would be empty. No one said a word in response except Dr Iqbal who smiled and said, ‘Indeed’”.

Hasher whose poem had outshone Allama Iqbal’s on that day, could be sarcastic. Humility, sadly, had not touched him.

Batalwi reports that Hasher was a prolific writer. He was known to dictate to two scribes simultaneously, one sitting on each side of him, and when in a mood, would dictate hundreds of pages in one sitting. In his earlier work, he used Urdu with a heavy influence of Persian. But later, having heard of his inability to write in Hindi, he wrote several dramas in Hindi that “had the pundits of Banaras in utter disbelief”. Such was his command of the language. Hasher’s talent went beyond drama. Batalwi narrates another incident of Hasher’s less-recognized poetic genius:

In 1935, Akhtar Sherani and I brought out a magazine Romaan. (Akhtar Sherani was the most popular romantic poet of that era). We had chosen the following verse of Akhtar for the title page:

Zarre zaare ka dil ek mohshar-e nazzara hey

Saaree dunya mere romaan ka gehwara hey

Akhtar and I went to see Hasher and showed him the first issue of our magazine. He looked impressed, went through it, and made several favorable comments. But having seen the verse at the title page, he looked irritated, “Who wrote this bad verse?” Akhtar looked embarrassed. Told that it was Akhtar’s, Hasher said, “So, Akhtar has come down to this level?” Hasher then thought for a couple of minutes and came up with the following verse:

Kaho zahid sey kiyon hey iss qadar Firdous per nazaan

Hazaroon jannatein abaad hein takhayal-e Akhtar mein

Not many had the talent to improve upon the romantic verse of the king of romantic poetry, Akhtar Sherani. One begins to wonder what Hasher would have achieved had he devoted all his time to poetry!

Respected journalist Abdul Majid Salak tells us about Hasher’s time in Bombay:

Hasher had joined a group of several young men, Abul Kalam Azad, Azad’s brother Ghulam Yasin Ah, and Nazir Hasan among others…they formed a debating (munazra) group. Every few days, they would debate a Christian priest or an Arya Samaji and would overwhelm them. It was not easy to win against the group that had the whole arsenal: Azad’s vast knowledge and intellect, Nazir’s extempore poetry, and Hasher’s powerful oratory and quip.

Salak who spent considerable time with Hasher in Lahore back in 1916, notes that several of Hasher’s dramas were adaptations of Shakespeare’s works. Hasher did not know English. He would hear the plot of a Shakespearean drama. Using his imagination and the exceptional gift of a playwright, he would then create an Urdu or Hindi masterpiece out of it that looked original. Shakespeare himself had borrowed the stories of many of his dramas from others and this does not diminish his or Hasher’s greatness. Hasher was “unique, a once-in-a-generation talent, who scaled tremendous heights in prose, poetry, oratory and drama,” Salak writes. Salak too noted Hasher’s vanity:

Hasher had received a check of Rs 5,000 one day as an initial payment from Seth Sohrabji for a drama. I found Hasher in a joyous mood that evening. And as you would expect, was full of admiration for himself. “Agha Hasher is the god of drama; no one in India is even close to Hasher; Hasher is India’s Shakespeare.” Being told that it was time to thank God and he should be humble rather than vain, had no effect on him; the hubris continued. Hasher’s vanity was an incurable disease.”

Hakim Ahmad Shuja met Hasher in Lahore in 1911 and became a lifelong admirer. He has devoted several pages of his autobiography to Hasher:

Hasher spoke without any formality like that of a poet or a king who doesn’t care much for what he says…I later discovered that there was far more to Hasher than a dramatist and a poet; he had a vast knowledge and understanding of Islamic history and religion.

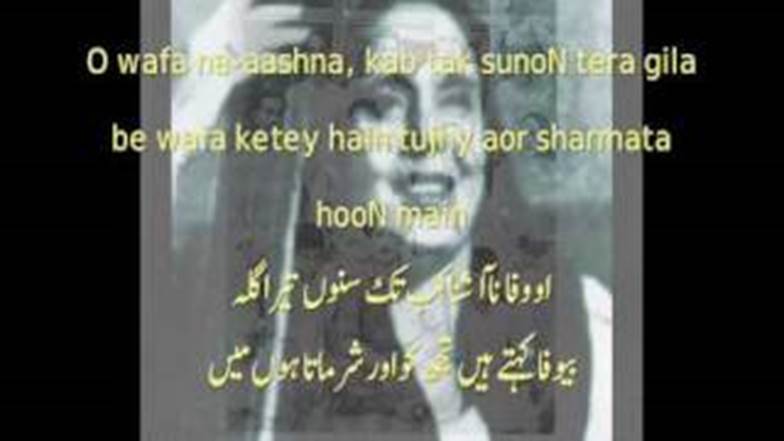

Mukhtar Begum sings Agha Hasher’s ghazal

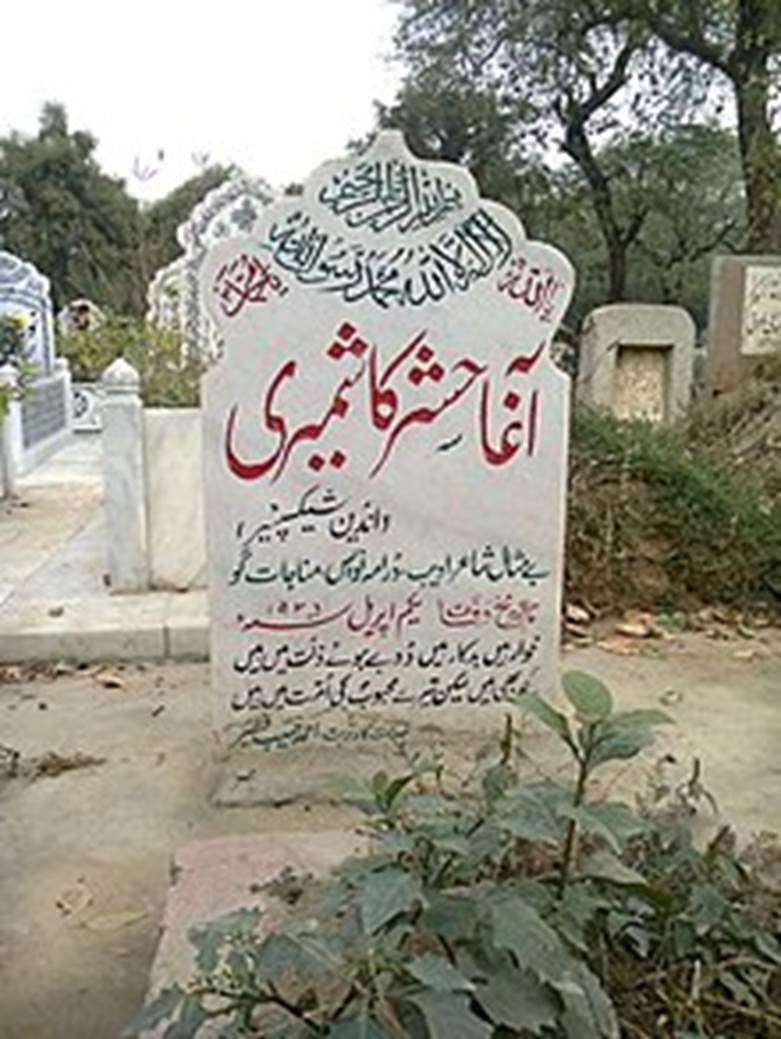

Hasher’s wife had been sick for some time and died in Lahore in 1916. As she was being lowered to the grave, Hasher kept sitting at the grave site. And then, using his stick, made a rectangle on the ground next to her grave and said, “This will be Hasher’s grave.” And that is where he was buried years later.

After her death, a devastated Hasher left Lahore for Calcutta where he achieved tremendous professional success as a dramatist. However, without a steady home life, he lost his way. Years of debauchery and drinking followed. That is until he met Mukhtar Begum. Finally, he returned to Lahore in 1934. He was in poor health. Years of drinking had taken its toll. Still, he continued to work and had several plans for his new film company, Hasher Pictures. Two days before death, he may have had a premonition when he recited the following - his last verse:

Kho chuka jo joshe taqat phir miley dushwaar hey

Hasher ab sehat meree girtee huwee dewaar hey

Shuja recounts that Hasher was very generous to his extended family. Regardless of his financial situation, he ensured that a considerable sum was sent every month to his mother which was then passed on to the widows, orphans, and poor relatives.

So, this was multi-talented Agha Mohammad Shah Hasher Kashmiri, an extraordinarily gifted but flawed individual, who ruled the world of drama in the Indian subcontinent for a quarter of a century. Mukhtar Begum outlived him by decades. Her last years were spent in relative obscurity in Karachi. Several years after Hasher’s death, she visited London and met Batalwi. “We reminisced about Hasher 6,000 miles from Lahore,” he writes. Her younger sister Farida Khanum later became a respected ghazal singer. Mukhtar Begum was issueless and brought up the daughter of her driver. It is said that she tried to train her in music. The young woman did not have the talent for singing but was a good dancer. She later became a successful film actress.

Shakespeare’s grave is visited by hundreds every day while Hasher is barely remembered. Not many know he is buried in Lahore

Today, Shakespeare, whom Hasher used to emulate, remains as popular as ever. His grave is visited by hundreds every day while Hasher is barely remembered. Not many know that he is buried in Lahore. Haider Ali Atish may have written the following verse for the likes of Agha Hasher:

Na gorey Sikandar na hey qabar Dara

Mitey namiyoun kay nishan kaisey kaisey

References:Khoon Baha by Hakim Ahmad Shuja; Yaraane Kohon by Abdul Majid Salik; Ganjay Farishtey by Saadat Hasan Manto; Chand Yadeen Chand Tausarat by Ashiq Hussain Batalwi.

The writer is a physician in Williamsport, PA, and may be reached at asifjaved@comcast.net

Back to Pakistanlink Homepage