Book & Author

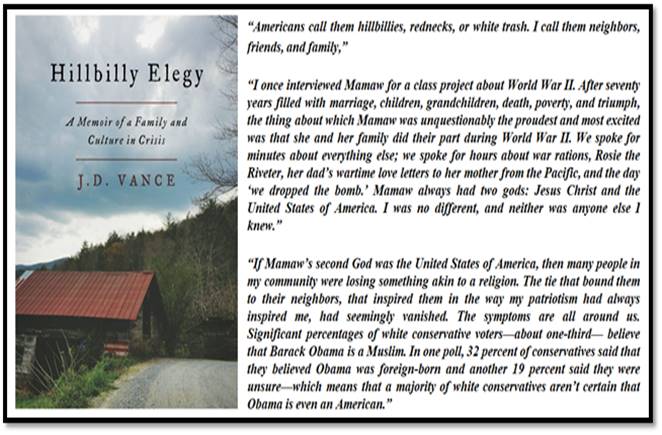

J.D. Vance: Hillbilly Elegy — A Memoir of Family and Culture in Crisis

By Dr Ahmed S. Khan

Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis by JD Vance, published in 2016 — months before Donald Trump won the presidential election — became a NYT bestseller. After President Trump announced JD Vance (JDV) as his running mate on July 15, 2024, Hillbilly Elegy is back on the bestseller list.

JDV, 39, would be the youngest vice president since Richard Nixon, who served two terms, starting in 1953, under President Eisenhower. JDV was elected from Ohio to the US Senate in 2022 and sworn into office on January 3, 2023. There is a major contrast between Trump and Vance — the former belonging to the American elite of inherited wealth and privilege, the latter representing the underprivileged (the Hillbillies of his book title). Indeed, politics makes strange bedfellows — Vance, once a Trump naysayer, is his running mate!

The book — spanning fifteen chapters — is an eye-opening autobiographical account of JDV’s journey out of poverty, violence, and despair; of joining the Marines and serving in Iraq, of pursuing higher education at the Ohio State University and Yale Law School; and of finally becoming an investment banker in Silicon Valley. Having moved from the lower to the higher economic strata, he could claim the achievement of his American Dream.

JDV shapes his account to enable readers to understand why so many people from the Rust Belt voted for Trump and embraced his slogan “Make America Great Again,” believing that Trump stood with them and would bring back all those jobs which had been lost to China and India.

The author has juxtaposed his life story with many ailments found in the broader society: class divisions, drug abuse, social welfare fraud, and economic disparity in Appalachia — the eastern region covering thirteen states —from southeastern New York down to the Appalachian Mountains, all the way to the northern parts of Alabama, Mississippi, and Georgia. JDV highlights a life story of growing up in the hills of Eastern Kentucky among people “Americans call … hillbillies, rednecks, or white trash. I call them neighbors, friends, and family.” The author praises family members who helped him move forward in various phases of his life: His grandfather (papaw), grandmother (mamaw), mother, aunt, uncle, sister, and later his wife. Mamaw was the matriarch of the family advising and supporting JDV from childhood to adulthood. Her love and strict discipline enabled JDV to succeed in his pursuits.

The author starts the book with a confession: “My name is J.D. Vance, and I think I should start with a confession: I find the existence of the book you hold in your hands somewhat absurd. It says right there on the cover that it’s a memoir, but I’m thirty-one years old, and I’ll be the first to admit that I’ve accomplished nothing great in my life, certainly nothing that would justify a complete stranger paying money to read about it. The coolest thing I’ve done, at least on paper, is graduate from Yale Law School, something thirteen-year-old J.D. Vance would have considered ludicrous…I am not a senator, a governor, or a former cabinet secretary. I haven’t started a billion-dollar company or a world-changing nonprofit. I have a nice job, a happy marriage, a comfortable home, and two lively dogs. So I didn’t write this book because I’ve accomplished something extraordinary.”

Continuing his confession, JDV further states: “I wrote this book because I’ve achieved something quite ordinary, which doesn’t happen to most kids who grow up like me. You see, I grew up poor, in the Rust Belt, in an Ohio steel town that has been hemorrhaging jobs and hope for as long as I can remember. I have, to put it mildly, a complex relationship with my parents, one of whom has struggled with addiction for nearly my entire life. My grandparents, neither of whom graduated from high school, raised me, and few members of even my extended family attended college. The statistics tell you that kids like me face a grim future—that if they’re lucky, they’ll manage to avoid welfare; and if they’re unlucky, they’ll die of a heroin overdose, as happened to dozens in my small hometown…Today people look at me, at my job and my Ivy League credentials, and assume that I’m some sort of genius, that only a truly extraordinary person could have made it to where I am today…Whatever talents I have, I almost squandered until a handful of loving people rescued me. That is the real story of my life, and that is why I wrote this book.”

Reflecting on the ethnic dimension of his story, JDV notes: “There is an ethnic component lurking in the background of my story. In our race-conscious society, our vocabulary often extends no further than the color of someone’s skin—“black people,” “Asians,” “white privilege.” Sometimes these broad categories are useful, but to understand my story, you have to delve into the details. I may be white, but I do not identify with the WASPs of the Northeast. Instead, I identify with the millions of working-class white Americans of Scots-Irish descent who have no college degree. To these folks, poverty is the family tradition—their ancestors were day laborers in the Southern slave economy, sharecroppers after that, coal miners after that, and machinists and millworkers during more recent times. Americans call them hillbillies, rednecks, or white trash. I call them neighbors, friends, and family.”

Recalling his early life, JDV observes: My father, Don Bowman, was Mom’s second husband. Mom and Dad married in 1983 and split up around the time I started walking. Mom remarried a couple years after the divorce. Dad gave me up for adoption when I was six…When Bob became my legal father, Mom changed my name from James Donald Bowman to James David Hamel Our new life with Bob had a superficial, family-sitcom feel to it.”

Discussing the abuse of the welfare system and policies and his limited income, JDV states: “I also learned how people gamed the welfare system. They’d buy two dozen packs of soda with food stamps and then sell them at a discount for cash. They’d ring up their orders separately, buying food with food stamps, and beer, wine, and cigarettes with cash. They’d regularly go through the checkout line speaking on their cell phones. I could never understand why our lives felt like a struggle while those living off of government largesse enjoyed trinkets that I only dreamed about…Every two weeks, I’d get a small paycheck and notice the line where federal and state income taxes were deducted from my wages. At least as often, our drug-addict neighbor would buy T-bone steaks, which I was too poor to buy for myself but was forced by Uncle Sam to buy for someone else…it was my first indication that the policies of Mamaw’s ‘party of the working man’—the Democrats—weren’t all they were cracked up to be.”

Commenting on the culture with no heroes, JDV notes: “As a culture, we had no heroes. Certainly not any politician—Barack Obama was then the most admired man in America (and likely still is), but even when the country was enraptured by his rise, most Middletonians viewed him suspiciously. George W. Bush had few fans in 2008. Many loved Bill Clinton, but many more saw him as the symbol of American moral decay, and Ronald Reagan was long dead. We loved the military but had no George S. Patton figure in the modern army. I doubt my neighbors could even name a high-ranking military officer. The space program, long a source of pride, had gone the way of the dodo, and with it the celebrity astronauts. Nothing united us with the core fabric of American society.”

JDV recalls an episode about his grandfather’s drinking habit and his grandmother telling Papaw that “if he ever came home drunk again, she’d kill him…. Mamaw, never one to tell a lie, calmly retrieved a gasoline canister from the garage, poured it all over her husband, lit a match, and dropped it on his chest. When Papaw burst into flames, their eleven-year-old daughter jumped into action to put out the fire and save his life. Miraculously, Papaw survived the episode with only mild burns.”

Reflecting on solutions to issues, JDV states: “People sometimes ask whether I think there’s anything we can do to ‘solve’ the problems of my community. I know what they’re looking for: a magical public policy solution or an innovative government program. But these problems of family, faith, and culture aren’t like a Rubik’s Cube, and I don’t think that solutions (as most understand the term) really exist. A good friend, who worked for a time in the White House and cares deeply about the plight of the working class, once told me, ‘The best way to look at this might be to recognize that you probably can’t fix these things. They’ll always be around. But maybe you can put your thumb on the scale a little for the people at the margins….There are, I think, policy lessons to draw from my life – ways we might put our thumb on that all-important scale.’”

JDV has described his wife Usha Chilukuri as “Yale spirit guide,” who helped him navigate life at the elite university where they met. He does not share details of his Indian wife’s family background but concludes the book by praising her: “Last, but certainly not least, is my darling wife, Usha, who read every single word of my manuscript literally dozens of times, offered needed feedback (even when I didn’t want it!), supported me when I felt like quitting and celebrated with me during times of progress. So much of the credit for both this book and the happy life I lead belongs to her. Though it is one of the great regrets of my life that Mamaw and Papaw never met her, it is the source of my greatest joy that I did.” Recently Usha has become the target of far-right people in US politics, and they have declared that “There is an obvious Indian coup taking place in the US right before our eyes (Stew Peters).”

In Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis, J.D. Vance juxtaposes his trials in growing up in poverty, within a dysfunctional family beset by drug abuse, with the struggles and challenges of America’s white working class in the Appalachian states; in the process, he exposes social, economic, class, and cultural divisions that are rarely covered by the main media.

The book has its shortcomings too: the narrative lacks a scholarly tone, personal and family stories are repeated multiple times, and the author tries to generalize his own opinions and observations by connecting them to various research findings. Despite such shortcomings, it is a moving memoir about the loss of the American Dream for a large segment of the white working class — and essential reading for all who desire to comprehend the rage and disaffection of large segments of Appalachia.

Dr Ahmed S. Khan ( dr.a.s.khan@ieee.org ) is a Fulbright Specialist Scholar. Professor Khan has more than 40 years of experience in Higher Education as professor of Electrical Engineering, Chair and Dean of the College of Engineering and Information Sciences. He is the author of many academic papers, technical and non-technical books, and a series of books on Science, Technology & Society (STS) — used globally in the academic programs of more than 200 universities.