Book & Author

Abd Al-Hadi At-Tazi: Eleven Centuries in the University of Al-Qarawiyyin

By Dr Ahmed S. Khan

Chicago, IL

“I had never seen like it [al-Qarawiyyin University] nor like its learned men neither in Telmsan nor in Bjaya or even in the region of esh-Sham, Hidjaz or Egypt.”

— Shaykh Ali Ben Maymoun (1450 -1511)

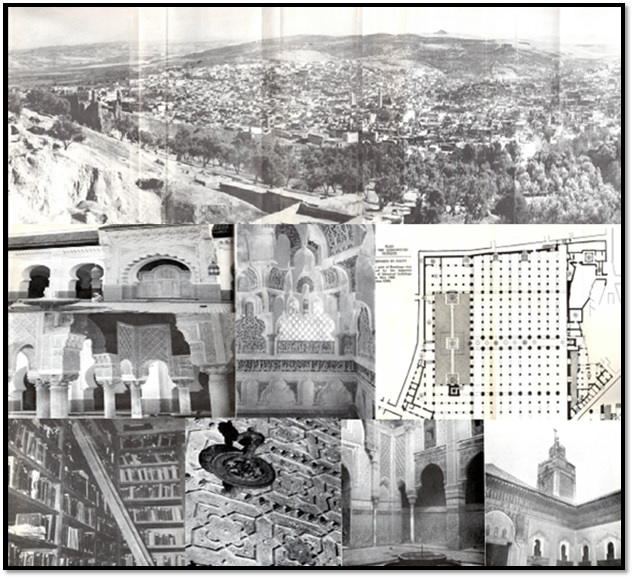

Al-Qarawiyyin is the oldest university in the world. For the past twelve hundred and sixty-three years Al-Qarawiyyin— also written as Al-Karaouine or Al Quaraouiyine — has been the premier religious and educational institution of the Islamic world. It was established in 859 AD by Fatima Al-Fihri, who migrated with her father Mohammed Al-Fihiri, a businessman, from Qayrawan, Tunisia to Fes, Morocco. The family settled in the western district of Fes which was inhabited by other migrants from Qayrawan. Fatima and her sister Maryam were well educated and had the passion to serve the community. They inherited a large amount of wealth — each decided to build a mosque for the community. The mosque built by Fatima came to be known as Al-Qarawiyyin, which eventually evolved into a university offering various programs in areas of natural sciences, Qur’an and Fiqh, medicine, mathematics, astronomy, chemistry, history, and geography.

Over the past twelve hundred years Al-Qarawiyyin has produced many great scholars including Abu Abullah Al-Sati, Abu Al-Abbas al-Zwawi, Ibn Rashid Al-Sabti (d.1321 AD), Ibn Al-Haj Al-Fasi (d.1336 AD), Abu Madhab Al-Fasi, Ibn Maymun (Maimonides, 1135-1204), Al-Idrissi (d.1166 AD), Ibn Al- Arabi (1165-1240 AD), Ibn Khaldun (1332-1395 AD), Ibn Al-Khatib, Alpetragius, Al-Bitruji, Ibn Harazim, and Ibn Wazzan.

During medieval times, Al-Qarawiyyin played a key role in promoting cultural exchange and transfer of knowledge between Muslims and Europeans. Among prominent European scholars who studied at Al-Qarawiyyin were Gerbert of Aurillac (930-1003 AD aka Pope Sylvester II, the Belgian Nichola Louvain, and the Deutch Golius. Unfortunately, some Europeans, like the French Empire builder, General Louis Lyautely (1854-1934) — who led the French “Civilizing Mission” in Morocco via creating a protectorate — have shown bias and disrespect for this premier seat of learning by calling it “the Dark House.”

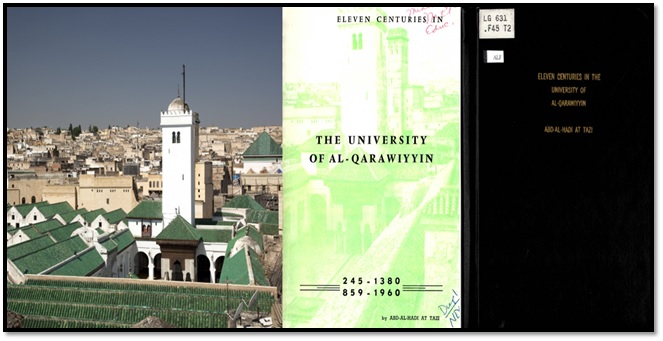

Eleven Centuries in the University of Al- Qarawiyyin (245-1380 AH/859-1960 AD) by Abd Al-Hadi At-Tazi chronicles the growth and emergence of the world's oldest university. The author was a professor and an attaché — in the Moroccan Ministry of Education — charged with cultural relations with the Arab countries. The book was translated into English by Daoud Handiya and published by the Moroccan Ministry of Education in 1960.

The author, in the foreword, reflecting on the history of Al-Qarawiyyin observes: “This paper is a short summary of the history of al-Qarawiyyin Mosque; however, no historian could pretend to digest eleven centuries of history in a few pages; and this is particularly true of a mosque whose history is bound up with not only that of Morocco itself but also with that of the North African communities, Andalus, and the Islamic world in general, Moreover, this mosque has been over the centuries the center of light and guidance for thousands of learned men, who taught others, of hundreds of leaders, scores of kings and chiefs whose own lives adorn the pages of history with their examples. Each particular aspect of this great mosque would need a great deal of research in itself; but here, we have presented a general perspective of events in the history of this university relying strictly on historical facts and leaving aside the “golden legend” attaching to this stream of existence. It is to be hoped that the reader will find in these lines something of interest concerning the history of this university which has played such an important role in the diffusion of Islam as a creed and the Arabic language as a tongue. ABD AL-HADI AT-TAZI, VI. 25.1960.”

Reflecting on the origin of the name of Al-Qarawiyyin, the author states: “In its early history Morocco experienced an influx of people who adopted it as second homeland, having come in thousands from Andalus at the time of El Hakam Ibn Hisham, and in hundreds from Qayrawan at the time of Aghlabids. The Imam Idris II, then reigning, took care of the new elements in the following manner: He designated the eastern part of Fas in the month of Rabia 1, 192 AH (January 808 AD) for Andalusian nobles, and this part became known as “the Andalusian quarter”; and in the month of Rabia IL 193 AH (January 809 AD), he chose the western part for himself and a group of Qayrawanis. Thus Fas became two-cities-in-one: the Andalusian city and the one inhabited by the Qayrawanien (a name which was simplified by the people into Qarawiyyin). Among the African emigrants who settled in Fas at the beginning of the third century AH was Mohamed Ben Abdullah al-Fahri al-Qayrawani, who died soon after his arrival, leaving a large fortune to his two daughters: Fatima and Maryam. Their nobility of nature was such that they conceived a project which was not only to redound to the glory of Muslim women to this day, but which has been a source of pride to all Muslims forever. Since many emigrants had gone to Fas, it was soon clear that the Shorafa Mosque in the western quarter and Al-Ashiakh Mosque in the eastern quarter, both founded by Idris II, were not sufficient for the needs of the people. Therefore, Fatima and Maryam volunteered to build mosques in the western part, the Qayrawani section, and in the eastern one, the Andalusian: the former was patronized by Fatima, the latter by Maryam. It was because of its situation that the mosque-university got its name.”

Describing the establishment of the mosque — The First Qarawiyyin 245 AH (859 AD) — the author notes: “Fatima chose a field in the eastern part of the Qarawiyyin city that had been inherited by a young nobleman of the Haouara tribe; she paid for it with some of her own pure fortune. Under the directions of the Sultan and some learned men, she began preparations for the construction on part of the ground, deciding to extract building materials from the site itself. She was pleased to discover a quarry, sand and at the same time, she dug a well close to the mosque which used it during its first years. By way of dedicating the work to a religious end, Fatima fasted for a while after the construction of the mosque was begun on the 1st of Ramadan, 245 AH (November 30, 859 AD). Like the first mosque, al-Qarawiyyin was square-shaped, but not perfectly square in as much as its length from east to west was 39 meters while its width was 32 meters. This means that the mosque was 1,248 square meters. Thus it was formed of 4 “Ascopes”, from west to east, and 12 ‘Blatas’ from north to south.”

Explaining the evolution — The Second Qarawiyyin 322 A.H. (934 AD) —the author observes: “After a century's use, the mosque began to suffer from narrow-ness and need for reformation. He who adopted reformation this time was Emir Ahmed Ben Abi Bakr Az-Zanati, who wished to crown his period by the decision to enlarge the mosque. He wrote to Emir Al Mouminin Abdur-Rahraan III, asking him to participate in the project of this enlargement. The Omayyad Khalipha considered this suggestion as an honor to him from his ally. Thus he sent an important amount of money, designated for construction, for the enlargement of the mosque. By this time, the mosque had been enlarged on three sides: west, east and north, a total of 2,748 square meters. Thus following this enlargement which had changed the first aspect of the Qarawiyyin, the mosque was composed of thirteen “Ascopes” and eighteen “Blatas”, while the surface became 3,996 square meters.”

Expounding further on evolution — The Third Qaramyyin 531 AH (1137 AD) — the author notes: “In the 12th century AD, a conference of religious leaders (Ulema) and jurisconsults (fuqaha) decided to assign the Qadi Abdul Haqq Ben Maecha to supervise the repair and modification of the mosque, after receiving permission from the Murabited Sultan Ali Ben Yousuf Ben Tashfin. The said Qadi bought neighboring lands and properties in the south, east, and west of the mosque. Further addition was 1,850 square meters. Thus al-Qarawiyyin's present aspect became composed of sixteen “ Ascopes” and twenty “Blatas,” and a surface of 5,846 square meters. By this time, the ‘university’ acquired its pulpit which replaced the Fatimid Umayyad one, and its central “Blatas” were decorated with the most beautiful arts and designs.”

Reflecting on — The Present Qarawiyyin [1960] — the author states: “Although al-Qarawiyyin was branded, either in the first or the second enlargements, by the nature of enlarging the building, it was distinguished at the time of Muahhid, Marinid, Outasid and Sa'did dynasties by equipment such as the great luster, Spanish bells, the ‘Beautiful fountain’, water clocks and new public utilities for the men of al-Qarawiyyin. Under the Alawids, its public utilities were repaired. The names of Moulay Ismail, Mohamed Ben Abdullah. and Mohamed V were added to the names of the sultans engraved there."

Reflecting on the Cultural History of Al-Qarawiyyin, the author observes: “…For the sake of clarity we can divide these eleven centuries into three periods. The first period begins from the middle of the third century to the middle of the seventh century AH (859-1250 AD), that is to say: the last days of Idrisids, Zanatids and Murabitids up to the time of Muahhids. The second period begins from the middle of the seventh century to the middle of the 11th century (1259-1665 AD), that is to say: at the time of the Murabitids, Outasids and the Sa'dids. The third and last period begins from the middle of the 11th century to the year 1380 AH (1665-1960 AD), that is to say: from the rising of the Alawid period to the present day.”

Discussing the First Period (859 - 1250 AD) — viz a viz a historical review of Idrisids, Zanatids, Murabits, and Muahhids — the author notes: “…the first Islamic dynasty appearing in Morocco was called the Idrisids, who planned and adopted Fas as their capital. In foreign affairs, it sought to maintain a certain neutrality between the Aghlabids in Africa and the Ommayads in Andalus. Upon the rise of the Fatimids in 305 AH the above dynasty could not keep such a policy as it had lent hand to the latter and invoke blessing to them on the mosques' pulpits. Facing this fact, Cordoba began to present promises to the Zanatids' leaders who took power in the country following the withdrawal of the Idrisids. For a while, the pulpit of Al-Qarawiyyin remained subject of competition between Cordoba and al-Qayrawan.”

Continuing with the First period, the author states: “At the beginning of the 5th century AH, Morocco again followed the policy of “independence”, and by that time Fas became the destination of learned men and poets who praised the mir of the city. The capital of Morocco enjoyed prosperous days, but the dispute of leaders disturbed its life. It was then that the Murabits under Yousuf Ben Tashfin established power over both Spain and Morocco. But their dynasty was soon overwhelmed by that of Muahhids under Abdul Mu'min who in 540 besieged Fas, revenging upon “Al-Mulatamin” destroying their traces and surrounding, at the same time, Qadi Ayyad in Ceuta. Marrakech became the capital of this immense empire; to it came philosophers, poets, mystics, and great religious leaders. Yet Fas remained an important center of intellectual life since it was centrally located.”

Commenting on al-Qarawiyyin's legacy as the oldest university, the author observes: “The Arab conquest was distinguished by the fact that it came to Morocco with “a Book.” And since the natural place for the meeting of believers was the mosque, where they could discuss the Qur'an and its contents. It was only natural that it should become a sort of school. Qaba'a mosque in Makkah was the first such school in the East; the first one built in North Africa was in al-Qayrawan. Many mosques were patterned after the latter in many respects, as for example, the az-Zaituna in Tunis, al-Qarawiyyin in Morocco and al-Azhar in Egypt, and so on. But these mosques did not always remain educational institutions besides being mosques, since now one place thrived, while another declined, and vice versa. But the one in Fas stands out because Fas was built not to be a commercial or industrial center but rather to be a religious and teaching center. Moreover, religious leaders and jurisconsults controlled the growth of the city from the very first day. Religious education had never stopped even during periods of repair and even when Marrakech became the capital of the country at the time of the Murabits; the learned people of Marrakech and elsewhere in Morocco sent their sons to al-Qarawiyyin to be educated. If the University of Bologna in Italy was founded in 1088, Oxford in 1096, the Sorbonne in 1257, then it is not difficult to see that the Qarawiyyin is among the oldest universities in the world; and one can perhaps add that the oldest university in the world is not in Europe but in Africa.”

Describing the subjects of studies, the author notes: “Since its appearance al-Qarawiyyin acquiesced in Imam Malik's creed which came into Morocco with Idrisids, in support of Cordoba and al-Qayrawan. Thus Malik's creed and opinions and the books written by his pupils were the main subjects studied in addition to other sciences. It was during the Murabitid period that the creed of al-Ghazali was repressed and his book al-Ahia'a burnt at the beginning of the sixth century A.H. But with the coming of the Muahhid Dynasty, the Muahhids laid down a new program aim[ed] at the study of old books of “Hadith” written by: al-Boukhari, Muslim, al-Tirmazi, Malik and Abou Daoud. It was an appeal to pave the way for “Ijtihad,” so that the name of al-Ghazali appeared again. The Muahhids also paid attention to different sciences and arts with the help of the teachers who came from Andalus.”

Reflecting on the teachers’ income, the author states: “Since the beginning of the 6th century AH the budget of al-Qarawiyyin was about eighty thousand Dinars, equal to one million and sixty thousand Dirhams, Moroccan present currency [1960]. This is to let one understand the fertile source designated at that time for al-Qarawiyyin and its men so that they were able to fulfill their mission perfectly.”

Explaining the role of the director of the university, the author notes: “In general, the Qadi of Fas has had the direction of the university under his control. He appoints the professors, the prayer leaders and supervises the construction and repair work, not to mention managing the budget. The Qadis Ben Maecha and Abdullah Ben Daoud were among the most famous.”

Describing Pope Sylvester’s relationship with al-Qarawiyyin, the author observes: “Nowadays students go from Morocco to Europe for education; but in the medieval times many Europeans used to go to Cordoba or elsewhere in Muslim Spain; and since in those days it was not difficult to go from Cordoba to Morocco, or vice versa, since they belonged to the same culture, many foreign students came to Al-Qarawiyyin. Among them was Gerbert d'Aurillac who later on became Pope Silvester II, as Christovitch said.”

Discussing the Second Period (648-1076 AH/1250-1665 AD) — viz a viz a historical review of Marinids, Outasids, and Sa’dids — the author notes: “Mouahhids could not resist before the pressure of the Marinids who took charge of Fas, where they established the ‘White City’ their court. As the Marinids' policy was to refer to Imam Malik's creed and books, since the beginning they constructed board schools which enabled them to control education, and at the same time to solve the problem of housing for the students who used to come in larger numbers to Fas…And despite wars in Spain, the Marinids continued constructing institutes, schools, and mosques everywhere so that the capital became the place of almost all intellectual persons. It was the turn of Abou Inan who left important cultural traces in addition to several schools. Then came Abou Faris for whom the history of Ibn Kholdoun was written. At the latest days of the Marinid dynasty, the mayors of the Palace captured power in their hands and some clashes occurred among them, while Andalus was breathing the last ghost, and migration continued from there to Morocco. Later on occurred the catastrophe of 818 AH (1415-1416) as Ceuta fell into the hands of the Portuguese. Facing such a situation, all Moroccans' efforts were mobilized to drive the Portuguese away from the “learned city.”

Describing the system of teaching and certificates during the second period, the author notes: “…the master-disciple system of teaching was employed, which was traditional in the East: students used to sit around the professor in circles, one circle after the other, so that sometimes there were as many as twenty circles. From time to time some Ulemas would sit among the students in order to follow certain points of view. One lesson may last from sunrise to midday. The morning lesson almost always concerned itself with religious jurisprudence while the afternoon lesson would be reserved for other subjects. In the summer, a slightly different arrangement was followed: the school was changed into an evening school, on account of the heat. Lessons began after the sunset prayer and lasted until midnight. Summer vacations of 40 days, Thursdays and Fridays, and the month of Ramadan broke the monotony of schoolwork. But even during these intervals of rest, studies such as literature and biographies were given.”

Reflecting on the Third Period (1076-1360 AH/1665-1960 AD) — viz a viz a historical review of the Alawid kings — the author states: “The Alawids were the only capable to restore calmness in Morocco, following their appearance in Sijilmassa. Their grandfather Ali al-Cherif was in full connection with the Ulema of Fas. The first sovereign, Moulay Rashid, took possession of the north of Morocco. His successor on the throne, Moulay Ismail, who reigned for 55 years (1672-1727), managed to give Morocco a period of stability such as had never known before. He made the Spaniards relinquish Mahdia and Larache. Upon his death, the country returned to anarchy for a while. His son Moulay Abdallah was constantly in the center of difficulties surrounding possession of the throne. It was with Moulay Sliman (1792-1822) that the dynasty began to stabilize itself. He was himself a graduate of the Qarawaiyyin…The next Sultan, Moulay Abd ar-Rahman Ben Hisham (1822-1859), saw the invasion of Algeria by the French and was defeated at the battle of Isly (1844). His son Moulay Mohammad who recognized that the subjects studied in al-Qarawiyyin became no more sufficient. Later on, Moulay al-Hassan agreed with his father's opinion and approved certain regulations which he believed were necessary to enable the Qarawiyyin to preserve its entity. Soon he died, and upon the beginning of 1331 (1912) French protectorate was imposed on Morocco, and the capital was transferred from Fas to Rabat. After bloody days and forty years of struggle, Morocco under the leadership of King Mohammad V recovered its sovereignty and began to construct its independence on strong wise bases.”

Expounding on the foundation of the educational system at al-Qarawiyyin during the third period, the author notes: “Al-Qarawiyyin university continued its traditional teaching and systems. The professors used to choose the books they liked and studies they wanted. The first king who laid down new regulations for al-Qarawiyyin was Sultan Mohammad III. It was 1123 [AH] (1789 [AD]) that he issued a law ordering the Shaikh of al-Qarawiyyin to define the subjects of teaching in this university as well as the books to be used. History books refer that the king took this decision after a consultation with many Ulema, some of whom were from Egypt.”

Reflecting further on the state and status of al-Qarawiyyin — viz a viz One Hundred Chairs And Twenty Libraries — during the third period, the author observes: “At that period, different sources affirm that there were one hundred professor chairs in Fas, distributed on the two hundred fifty sections of al-Qarawiyyin, that existed in every corner and street of the city. That is in addition to one hundred and six primary schools, some of which were designated for girl students. Out of these chairs, twenty were in al-Qarawiyyin itself. The system of promotion for these chairs was in a way similar to the means followed in modern institutes. That is to say: when a chair is vacant another professor has to be promoted after the Qadi's approval. Each chair has had its own professor, its private book and its own Habous [endowment/waqf]. Moreover, all these institutes have had libraries full of manuscripts for the students' use…A general tendency towards reform of the program of teaching was in evidence in 1261 AH (1885) as Sultan Abd ar-Rahman Ben Hisham sent a Dahir to the Shaikh of al-Qarawiyyin and Qadi of Fas, criticizing the system of teaching and the useless means followed in this field, requesting the professors to reform the program and means of teaching…Sultan Mohammad IV thought of sending groups of students to the East and Europe to assimilate whatever learning that region had to teach. It was then that a “stone press” appeared for the first time in Fas. It greatly influenced the progress of culture and the spread of knowledge among the Ulema and students of al-Qarawiyyin. Moulay al-Hassan followed the steps of his father as he sent missions of students to Egypt and different European nations. He also encouraged the press to continue its efforts.”

The author, reflecting on challenges Al-Qarawiyyin faced during the period of resistance, states: ”At the end of the 18th century, the men of al-Qarawiyyin were subject of a furious campaign directed against them by some foreign writers who came to Morocco within private missions. They qualified the former as “opposers of development” and denounced their knowledge and abilities. But those who know the status of al-Qarawiyyin and its influence among the authorities and the people at that period can easily understand the secret of the said writers' aim.”

Describing further the period of resistance, the author observes: “As the protectorate spread its influence over Morocco, it tried to be sure of what is going on inside the Qarawiyyin, in the “criminal city,” as it was described by General Moinier, especially inasmuch as Moulay Yusouf expressed his desire that teaching should be developed. The protectorate attempted to impose its supervision on al-Qarawiyyin; thus for the first time in history, the administration of this university was removed from the control of the Qadi, and a “Council” was set up in the presence of Mr Mercier and Captain Meili, on Thursday Jamada Tania, 1332 (May 17, 1914). In 1932, a legislation was issued defining the periods of teaching into three: Elementary, secondary, and high including two sections of specialization in religion and literature. Progress of al-Qarawiyyin was not only impossible but also undesirable, and as the first protest against the “Berber policy” rose in the Qarawiyyin, the students were subject to pressure, and young Ulema were prevented in 1932 from the promotion to the chairs of al-Qarawiyyin. The students understood that the situation was going from bad to worse, in 1937 they went on strike and in 1942, King Mohammad V could acquire an agreement to appoint a graduate of the Sorbonne and old student of the Qarawiyyin as director of the University of Fas. The High Council under the presidency of H.M. King Mohammad V began to pay attention to Islamic institutes and education, so that the people expected a further rise for al-Qarawiyyin. The claim for independence of the country in 1944 was sufficient to send the students of al-Qarawiyyin to prisons. Events went on... a new institute for girls was added to al-Qarawiyyin at this period, yet all attempts for reformation in 1947 were in vain. It was 1951 when General Juin found a suitable occasion to take revenge from the Qarawiyyin, which he considered an opposer of imperialism and its puppets.”

The author concludes the book by describing the rising of Qurrawiyyin University after the independence: “As the Moroccan Kingdom recovered its sovereignty, old Qarawiyyin University and Morocco opened their eyes after independence to find themselves before a generation of different preparation: Some ones' culture is Arab Islamic, while others' is foreign. Facing this fact, the Royal Committee, found in 1957 that the ideal solution is to unify the educational programs of all schools, including the different stages of education in religious institutes. Moreover, H.M. the King has remitted to the Ministry of Education the keys of a large fortress to be a university quarter for al-Qarawiyyin instead of the old traditional one. Later on, a Supreme Council of Education has been created; this council took decisive steps in 1960. Thus all efforts that have been made to realize the said unification were achieved in the first stage, which is considered as the bases of other different branches. Then comes the secondary stage which may bring the student to either college Islamic Law or literature, or to other colleges which are going to be adopted by the rising Qarawiyyin University, which will undoubtedly reflect the glory of eleven centuries. That is to say from the time of Idrisids. Such is al-Qarawiyyin; every Moroccan citizen must be proud of it and must not forget this name which had been engraved in the mountains, the desert, in town and village. This name, which has fought against ignorance and confusion everywhere, must remain in our glorious tradition.”

Al-Qarawiyyin University’s website http://uaq.ma/index.php/forward-president-of-al-quaraouyine-university presents current curricula and activities, listed mostly in Arabic. Considering the historic importance of Al-Qarawiyyin, international collaboration with academic institutions in the Muslim world can enhance the curricula offerings, and incorporation of online and new teaching methodologies can promote teaching, learning, and research in various disciplines greatly benefiting local and global students.

In Eleven Centuries in the University of Al-Qarawiyyin, Abd al-Hadi At-Tazi has chronicled the history of Al-Qarawiyyin, the world’s oldest university — evolution from a Mosque to a Modern University — spanned over the past eleven centuries. It is a historical document — a must-read for all students and teachers of history and Islamic studies.

(Dr Ahmed S. Khan - dr.a.s.khan@ieee.org - is a Fulbright Specialist Scholar)