Book & Author

Christophe Jaffrelot:Modi’s India — Hindu Nationalism And The Rise of Ethnic Democracy

By Dr Ahmed S. Khan

“India should follow the German example to solve the Muslim problem… Germany has every right to resort to Nazism and Italy to fascism – and events have justified those isms…”[1938]

American interviewer Tom Treanor [1944]: How do you plan to treat the Mohammedans? "As a minority…in the position of your Negroes…And if the Mohammedans succeed in seceding and set up their own country?... There will be civil war."

Vinayak Damodar (“Veer”) Savarkar: Ideologue of Hindutva

Over the past two decades, Narendra Damodardas Modi using Hindu nationalism — Hindutva —has steered the world's largest secular democracy toward authoritarianism and intolerance. Today in India the electorate is totally polarized on ethno-religious lines. Modi has transformed India from a de facto Hindu Rashtra [nation] to an authoritarian Hindu Raj (Hindu nation-state). The recent Canada-India diplomatic row over Sikh assassination has revealed the global dimensions of Hindutva.

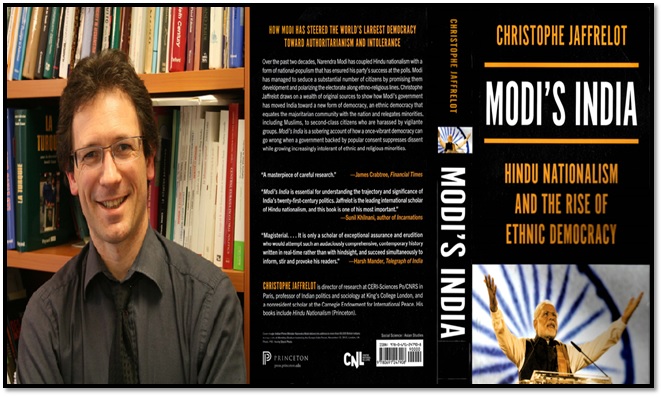

Christophe Jaffrelot’s scholarly work Modi’s India — Hindu Nationalism And The Rise of Ethnic Democracy relies on a plethora of original sources to show how Modi's government has moved India toward a new form of democracy — an ethnic democracy —that equates the majoritarian community with the nation and relegates minorities, including Muslims, to second-class citizens who are harassed and lynched by vigilante groups. Modi's India is a sobering narrative of how a once vibrant secular democracy can be transformed into an ethnic democracy when a government backed by popular consent suppresses dissent while growing increasingly intolerant of ethnic and religious minorities, especially Muslims. The book has been translated from French to English by Cynthia Schoch.

Christophe Jaffrelot is director of research at CERI-Sciences Po/CNRS in Paris. He is a professor of Indian politics and sociology at King's College London, and a nonresident scholar at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. His research focuses on theories of nationalism and democracy, mobilization of the lower castes and Dalits (ex-untouchables) in India, and the Hindu nationalist movement. His other major work includes Hindu Nationalism.

In addition to the Introduction (The Three Ages of India's Democracy), Conclusion, Notes (147 pages), and Bibliography (10 pages), the Book has three parts spanning eleven chapters: Part-I. The Hindu Nationalist Power Quest: Hindutva And Populism (1. Hindu Nationalism: A Different Idea, 2. Modi in Gujarat: The Making of a National-Populist Hero, 3. Modi's Rise to Power, or How to Exploit Hope, Fear, and Anger, 4. Welfare or Well-Being? ) Part-II. The World’s Largest De Facto Ethnic Democracy (5. Hindu Majoritarianism against Secularism, 6. Targeting Minorities. 7. A De Facto Hindu Rashtra: Indian-Style Vigilantism) Part-III The Indian Version of Competitive Authoritarianism (8. Deinstitutionalizing India, 9. Toward "Electoral Authoritarianism": The 2019 Elections, 10. The Making of an Authoritarian Vigilante Stat, and 11. Indian Muslims: From Social Marginalization to Institutional Exclusion and Judicial Obliteration).

In the introduction, reflecting on “The Three Ages Of India's Democracy,” the author notes: “India, even though it claims to be ‘the world's largest democracy’ due to the number of voters it regularly calls to the polls…has always been a ‘democracy with adjectives.’ However, the adjectives have changed over the years, with the country going from a ‘conservative democracy’ to experiencing a ‘democratization of democracy’ and today inventing a variant of ‘ethnic democracy.’”

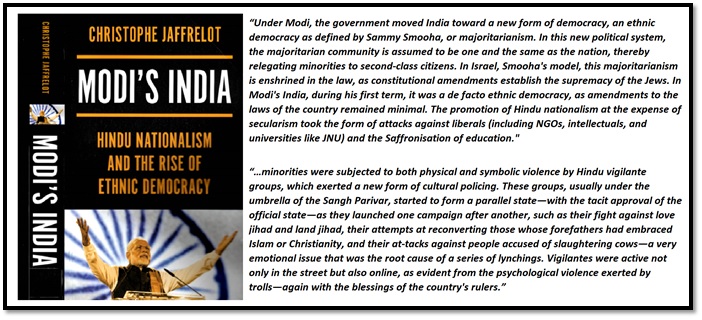

Expounding further on ethnic democracy, the author states: “Under Modi, the government moved India toward a new form of democracy, an ethnic democracy as defined by Sammy Smooha, or majoritarianism. In this new political system, the majoritarian community is assumed to be one and the same as the nation, thereby relegating minorities to second-class citizens. In Israel, Smooha's model, this majoritarianism is enshrined in the law, as constitutional amendments establish the supremacy of the Jews. In Modi's India, during his first term, it was a de facto ethnic democracy, as amendments to the laws of the country remained minimal. The promotion of Hindu nationalism at the expense of secularism took the form of attacks against liberals (including NGOs, intellectuals, and universities like JNU) and the Saffronisation of education."

Commenting on Modi’s cultural policing of minorities the author observes: “…minorities were subjected to both physical and symbolic violence by Hindu vigilante groups, which exerted a new form of cultural policing. These groups, usually under the umbrella of the Sangh Parivar, started to form a parallel state—with the tacit approval of the official state—as they launched one campaign after another, such as their fight against love jihad and land jihad, their attempts at reconverting those whose forefathers had embraced Islam or Christianity, and their attacks against people accused of slaughtering cows—a very emotional issue that was the root cause of a series of lynchings. Vigilantes were active not only in the street but also online, as evident from the psychological violence exerted by trolls—again with the blessings of the country's rulers.”

The author believes that India's trajectory from national populism to ethnic democracy suggests three general conclusions. Discussing the first conclusion, the author notes: “… in twenty-first-century India, the moderation thesis seems less relevant than the polarization thesis. A number of political scientists have postulated that extremist parties tend to dilute their ideology once they begin to participate in the democratic process of electoral politics. The moderation thesis in particular holds that electoral competition prompts extremist parties to adopt a less exclusivist program with each successive election in order to cast a wider net... For the BJP under Modi, waving a largely exaggerated Islamic threat and orchestrating communal violence were viewed as the best way to mobilize a ‘Hindu vote’ whenever the situation was conducive to such agitation. And in the early 2000s, the spat of Islamist attacks—some of which were planned by Indian Muslims retaliating against Hindu nationalists' atrocities—revived the majority feeling of vulnerability that the Sangh Parivar could easily exploit. The key role played by the RSS also shows that contrary to the moderation thesis, political parties playing by the rules of party politics cannot turn their backs on the radical movements that spawned them…Once in power, it [BJP] pursued the same path to win one regional election after another, playing on the same politics of fear that targeted both Muslims and the alleged Pakistani threat.”

Reflecting on the second conclusion, the author states: “Modi's policies have confirmed the hypothesis … which postulated that the Sangh Parivar's recourse to large-scale national-populist mobilization was a response to the rise of lower castes in the years 1990-2000. National populism was a reaction to the risk of a loss in status facing the upper-caste middle class—BJP's core electorate—and the risk of division that caste politics posed to Hindu society. By mobilizing Hindus against Muslims, the Sangh Parivar prompted large swaths of the masses to no longer put their caste identity forward but instead their membership in the majority community that was destined to rule over India…. In a way, the BJP reconstituted a coalition of extremes that was intended not only to mobilize against the other (the Muslim) but also to sandwich common enemies of the elite and resentful plebeians improving their well-being…Flagship schemes such as the Swachh Bharat Mission contributed to this strategy: like most of the centrally sponsored schemes, it was marketed—backed by a huge advertising budget—as a gift of Narendra Modi to the poor, whom he started to address every month in the Mann Ki Baat radio program from 2014 onward…His [Modi’s] relationship with some of India's big businesses constituted a prime example of crony capitalism, which his close contacts were the first to benefit from. This connection enabled the BJP to raise funds for his election campaigns.”

Expounding on the third conclusion, the author observes: “… the Indian variant of ethnic democracy needed to be qualified: in contrast to the Israeli ‘model,’ during Modi's first term India invented a de facto ethnic democracy in which the Constitution and most laws remained unchanged and in which the government remained in the background—mostly silent. Certainly, the state promoted the Hindi, nationalist version of Hindu identity, Indian history, and the role of minorities in society and history. But it left most coercive actions to non-state actors, such as to vigilante groups that exerted cultural policing in the street or to trolls doing the same on social media. This division of labor reflected not only the strategy of the Modi government but also the evolution of the Sangh Parivar. Since the 1980s this movement has developed subsidiaries intended to reach out to Dalits, OBCs, and upper-caste youth from the lower middle class. The Bajrang Dal was especially good at attracting jobless plebeians, who improved their self-esteem and even acquired a new identity, by fighting the enemies of Hinduism. Emulating elite groups associated with the Hindu high traditions, which were more than happy to co-opt them and subcontract their dirty work to them, these lumpen elements epitomized a new version of Sanskritization. Bajrang Dalis and gau rakshak were the foot soldiers of the de facto ethnic democracy that India became after 2014…their brutal, illegal actions were not punished, and the impunity of their patrolling of society was acknowledged not only by the majority community but, nolens volens, by many of their victims, who no longer dared to turn to the state for help. In a de facto ethnic democracy, the motto ‘might is right’ works in favor of majorities… Hindu nationalism indeed propagates an irenic view of society by minimizing social hierarchies and making them more acceptable…Indeed, the atmosphere created by Sangh Parivar vigilante groups and BJP IT cell trolls has been largely responsible not only for the lynchings of Muslims but also for attacks on ‘liberals,’ including intellectuals and journalists…while under Modi I, nonstate actors were responsible for their oppression, under Modi II, the state and its institutions directly targeted them, largely because the 2019 elections had enhanced the government's authority—in the upper house in particular. In six months, a whole series of legal changes took place, ranging from the abrogation of Article 370 to the Citizenship Amendment Act, two major decisions reflecting the will of Modi II to transform India into a more unitary state with a majoritarian overtone… Furthermore, beyond legislative changes, the BJP's authoritarianism viz a viz Muslims is reflected in the way opponents are quashed: hundreds of political prisoners were detained under draconian laws in Jammu and Kashmir, and anti-CAA demonstrators were also targeted by the police and jailed in large numbers. The police—which until then had allowed vigilantes to operate instead of systematically showing their anti-minority bias—turned against Muslims even more openly during the Delhi riots of February 2020.”

Commenting on National-Security Populism viz a viz resisting Pakistan and delegitimizing Congress, the author observes: “In 2019, Modi's heroic status was nurtured by his image as a strongman in the context of security threats. The Pakistani threat has always figured prominently in Modi's election campaigns… But he had never been in a position to exploit this factor as extensively and as successfully as in 2019. On February 14, 2019, barely a few weeks before the beginning of the official campaign, a deadly attack in Pulwama (Jammu and Kashmir)… By way of response, Modi ordered air strikes to be conducted on Pakistani territory. In the operation, the Indian Air Force lost a plane and a pilot, Wing Commander Abhinandan Varthaman … and mistakenly shot down one of its own helicopters, killing six airmen.' Despite the mixed results of these air strikes, Modi managed to portray himself as India's protector in a campaign dominated by nationalist and even warmongering rhetoric—largely because the fact that six airmen had died was hardly reported by the media…Modi himself used martial rhetoric aimed at disqualifying Congress leaders as antinational because, ‘guided by their Modi hatred [they] have started hating India,’ not only had they never dared to attack Pakistan the same way, but now they also even sought more detailed information about the Balakot operation—‘demoralizing jawans [soldiers].’ “To muster support before coming elections, Modi can go to any extremes; Mamata Banerjee, the Chief Minister of West Bengal has observed that BJP is planning to pull off another Pulwama-like ‘staged incident.’ She also said that BJP people are planning to create fake and staged videos for such staged incidents.

In the conclusion, the author poses the question “Why is authoritarianism not resisted more vigorously in India?” And then offers four explanations that are not mutually exclusive: “The first reason has to do with the fact that populists-turned-authoritarians do nothing illegal at the start, and they adopt an incremental modus operandi. As Levitsky and Ziblatt have shown, ‘This is how democracies now die. Blatant dictatorship—in the form of fascism, communism, or military rule—has disappeared across the world. Military coups and other violent seizures of power are rare. Most countries hold regular elections. Democracies still die, but by different means. Since the end of the Cold War, most democratic breakdowns have been caused not by generals and soldiers but by elected governments themselves..’

Pointing out the second reason, the author notes: “The second explanation may be that democracy, in today's India, has lost its importance, compared to security---a phenomenon that other countries have experienced before, including Pakistan, whose political background was similar to India's but which, fearing its big neighbor, became a security state in the 1950s…The need for a strong state further arises from the drive to stifle unresolved issues and conflicts, as evident from the fact that a "63% majority believes the government should be using more military force ‘in Kashmir.'”

Reflecting on the third reason, the author notes: “The third explanation harks back to the political culture of India and the traditional submission to hierarchy and acceptance of authority, that of a charismatic leader in particular…The words that Modi's supporters (known as bhakts [devotees]) use to describe his power often belong, indeed, to the realm of supernatural forces. Certainly, this image has Narendra Modi has acquired charisma in the Weberian sense owing to the manner in which he has achieved "big things"—which were not necessarily perceived as good things, as evident from the way the 2002 pogrom was reported in the media. He has shown his strength through disruptive decisions affecting the life of all citizens, such as demonetization. He has demonstrated his taste for the spectacular, with the statue of Sardar Patel, the tallest in the world. He convinced the UN to recognize June 21 as International Yoga Day. He has dared to attack Pakistan militarily beyond the territory of disputed Kashmir in Balakot. And he has initiated policies no one has ever attempted, such as the abolition of Article 370. But Modi is seen as exceptional not only on account of his acts but also owing to his style.”

Commenting on the fourth reason, the author notes: “… Modi, due to his social background, appears as a man of the people who has suffered from class and caste hierarchies and who cultivates a sense of victimization that Indian plebeians cannot help but share. He also cultivates his proximity to the people through his monthly radio program, Mann Ki Baat. To sum up, Modi is a pure populist a la Ostiguy because he combines these exceptional achievements and a sense of morality with a very humble background, which means that he is seen as "a man like us who managed to become a superman." This is the main reason why he is not punished by voters when he fails to deliver on the economic front.”

The author as the concluding remark observes that even an electoral defeat cannot attenuate BJP’s resolute march towards crafting a new hegemony because: “First …the Sangh Parivar is so deeply entrenched in the social fabric that it may continue to dictate its terms to the state on the ground—and to rule in the street. Second, the ‘deep state’ may remain in a position to influence policies and politics even if the BJP is voted out. In that sense, Hindu nationalism does not rely as much on one man to push its agenda as the BJP does to win elections.”

Modi’s India — Hindu Nationalism And The Rise of Ethnic Democracy by Christophe Jaffrelot is essential reading for understanding the course and significance of India's twenty-first-century politics. The author is the leading international scholar of Hindu nationalism, and Modi’s India represents his comprehensive scholarly work that educates the reader about the contemporary history of India.

(Dr Ahmed S. Khan is a Fulbright Specialist Scholar)