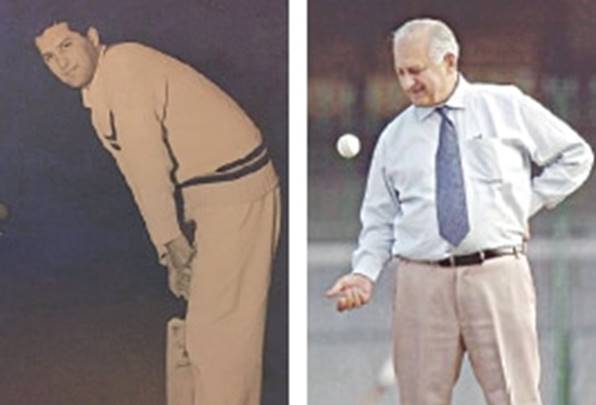

Author David Page called cricket Shaharyar’s ‘first love’, and his ‘outdoorsy’ mother Abida Sultan is thought to be the main influence for his love of sport — Family archive/AFP file

The ‘Prince’ Who Used His Diplomatic Skills to Serve Cricket

By Muhammad Ali Siddiqi

Karachi, Pakistan

When he was 16, Shaharyar Khan gave up a crown that legitimately belonged to him, for his love of Pakistan. Begum Abida Sultan, the crown princess of the culturally rich and glittering state of Bhopal with its 19-gun salute was his mother, and President Ayub Khan, ever considerate, told the princess she was free to go back to Bhopal to reclaim her heritage.

The princess turned to her son, who was categorical: he would remain Pakistani until death.

Diplomat, author and sportsman, Nawabzada Mohammad Shaharyar Khan, who died on Saturday, was born into Bhopal’s Afghan Mirazikhel dynasty on March 29, 1934.

He was the son of Suraya Jah and Nawab Gauhar-i-Taj — her mother’s royal titles — in an extraordinary dynastic phenomenon where four women known as begums had ruled the country in succession, managing to survive and contributing to Indo-Islamic culture in the chaos of the post-Mughal, pre-British era.

Most remarkably, the state maintained Hindu-Muslim harmony, even though 90 per cent of the population was Hindu and the state was surrounded by Marhatta fiefdoms.

Shaharyar went to school at Dhera Dun, Cambridge and the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Boston, getting an education that prepared him for an eventful career in Pakistan’s foreign service, which he joined in 1957, retiring as foreign secretary in 1994 after 37 years.

Those who worked with him say Shaharyar conducted diplomacy and sport affairs with royal grace. Diplomacy was in his blood, because Abida herself had served as Pakistan’s ambassador to Brazil and Chile.

His home education was rigorous and began early in the morning — lessons in the Holy Qur’an, Urdu, Islamic studies, math, geography, history, science, handwriting, art and music, and the governess would teach English, besides manners, especially toward the opposite sex.

He loved sports, because as his mother says in her memoirs, he watched her play “outdoor games from morning till sundown”. However, he hated riding because it required getting up at five in the morning, and his large feet got stuck in the riding breeches. He proverbially came of age when he shot his first tiger at the age of 10.

Even though his mother was often identified as a “rebel princess”, Shaharyar was himself a conformist to the core, for his resplendent personality oozed every bit of the sophistication and panache that go into being a prince. Abida noted in her memoirs that even as a child, he exuded “a sort of inborn dignity” and developed “a manner of handling people, family elders, servants, sentries and villagers with great sensitivity and with perfect manners”. There is no doubt he honed these childhood qualities to perfection when he became a diplomat.

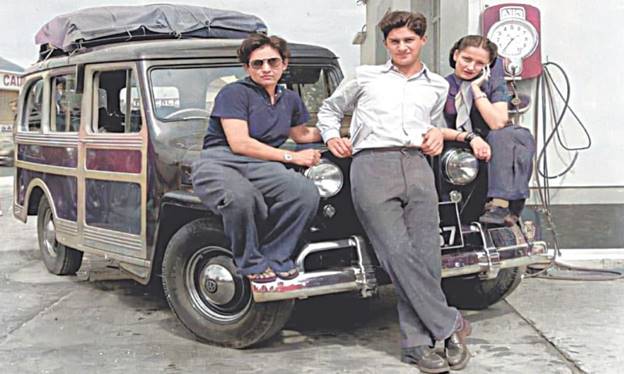

A young Shaharyar poses with his mother, Princess Abida Sultan (left), during a trip to Europe —Family archive

He had diplomatic postings not only at such sought-after places as Geneva, New York, Paris and London but also in a land of sorrow — Rwanda — where he was the UN’s special representative to report on one of the 20th century’s most gruesome African massacres. However, his true report on the Rwandan tragedy is his book — The Shallow Graves of Rwanda.

Consisting of a diary he kept to record the events he witnessed in the African country, it is considered the most authoritative account of the Rwanda massacre. He was “horrified” that the UN and the world community did not recognize that a genocide was taking place and therefore gave it the shape of a book to preserve the history of the massacre for posterity, because he feared the tragedy could “fade from public memory”.

Of the many books he wrote, The Begums of Bhopal was a monumental project that he undertook after retiring from diplomatic service. Until then, there was no standard family history, and he admits in his foreword that what the ruler-begums penned had “conveniently omitted” the battles lost, sovereignty surrendered and the deficiencies of their own character.

He personally worked hard to gather facts lying buried or forgotten in archives at Bhopal, Delhi and London, and managed to get hold of valuable records, including secret memos. Still, he admitted that his book should not be considered an authentic history of Bhopal.

His third book was on cricket, his passion. He was manager of the Pakistan team in 1999 and later chairman of the cricket board from 2003 to 2007. He co-authored, with Shashi Tharoor, Shadows Across the Playing Field: 60 Years of India-Pakistan Cricket, a book that dwells on the relationship between cricket and politics in the subcontinent. In his introduction, David Page calls cricket Shaharyar’s “first love” and says his diplomatic skills “were put to the service of cricket”.

Shaharyar not only played cricket, Page says, he “exercised an influence in the counsels of cricket both at home and internationally”.

Among other things, the book contains Shaharyar’s boyhood memories of the pre-partition Pentangular series in Bombay and the 1933-34 Bodyline series, which was the first time that ‘it isn’t cricket’ became a phrase. This made Shaharyar, says Page, write of the “the challenge cricket has faced ever since: how to preserve the values of the game in a world where winning has become so much more important”.

(The writer is Dawn’s External Ombudsman and an author. Dawn)