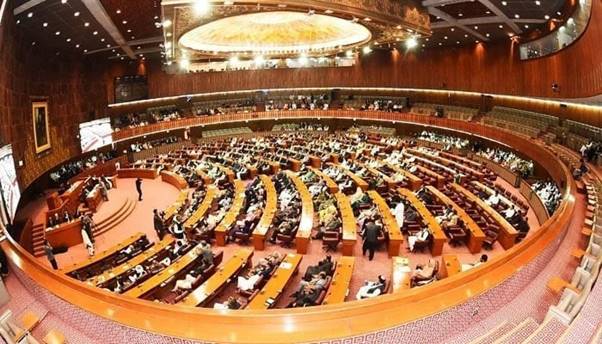

A view of the National Assembly session underway on April 10, 2023 — X@NAofPakistan

The Unsupremacy of Parliament

By Javed Jabbar

Karachi, Pakistan

To divert attention from the malevolent person-specific nature of most clauses in the 26th Constitutional Amendment Bill adopted helter-skelter without extensive public debate on October 20-21, 2024, the self-righteous refrain of ‘Parliament is supreme’ resounds from official circles.

In a state that employs a democratic process – however flawed or indirectly coercive – non-elected institutions and entities beyond elected legislatures are equally important, and at times, even more so. These institutions embody the cumulative wisdom gained through decades, and sometimes centuries, of experience. Their enduring strengths remain resilient against the fluctuations of fleeting public opinion, which is often susceptible to populism, economic crises, and emotional volatility.

The periodic overreach by the unelected judiciary and military is deeply troubling and should not be allowed to continue unchecked. Yet, their intrusive actions do not diminish the essential role of non-partisan institutions, organizations, and individuals in offering perspectives on issues of fundamental importance to the nation. Such entities include all forums of civil society – from bar associations and chambers of commerce to public policy research bodies, professional associations, farmers’ groups, and workers’ unions. While some may bring their own biases and interests, these are often well-known. Writers, artists, and other content creators contribute valuable, holistic insights that transcend the divisions of partisan conflict.

These sectors of society authentically represent the fundamental values, beliefs, and aspirations of a nation and do not require the ballot to legitimize their perspectives. In the hasty push to pass the 26th Amendment, none of these forums or individuals was given the opportunity to review or comment on the final draft. Even legislators saw the final version only minutes before it was rushed through.

All elected legislatures are bound by majoritarian rule. When ruling parties or coalitions leverage their simple majorities – ordinarily used for standard law-making – to reach the two-thirds threshold required for constitutional amendments, this transforms their majority control into a hostage-like grip, leaving no room for negotiation. Under the non-representative First-Past-The-Post (FPTP) electoral system, inherited from the British, even simple legislative majorities fail to represent the majority of voters, let alone two-thirds of the electorate.

In the FPTP system, a party getting a minority of popular votes can secure a majority of seats. In India, in 2024 the BJP received only 38 percent of the popular vote but became the single highest number in Lok Sabha seats and, with allies, became the lead ruling party for the third time. In the February 8, 2024 polls in Pakistan, all the overt and covert manipulations committed between Form 45 and Form 47 could not conceal a hard fact: PTI members who were compelled to contest as independents with a bewildering variety of election symbols instead of the famous PTI cricket bat symbol because of the ECP-Supreme Court alliance nevertheless secured more votes together than the two major parties whose candidates had the advantage of their long-used, well-known symbols. Surely, this is a first in global electoral history.

PTI-linked independents received over 18 million votes; PML-N candidates got only 14 million; and PPP contestants received only 8 million. Thus, out of a total of about 129 million registered voters of which only about 59 million turned out – less than 50 percent – the coalition that imposed the 26th Amendment with a two-thirds majority of seats in both houses of parliament actually represents only about 17.8 percent of the total registered voters and only about 44 percent of the votes cast (less than even a simple majority).

Two crucial constitutional amendments required to replace the FPTP system are not exactly hot favorites with legislators since they would need to work much harder to gain genuine majority support from voters. This writer has long been an advocate, including through essays in Dawn, to make voting compulsory (with disincentives for not voting) as is the case in 23 countries, and if no candidate receives more than 50 percent plus one vote in the first round, conduct a second or third round of voting with, say, the top three from the first round – till one candidate becomes truly representative of the majority.

Legislatures elected by the authentic majority of voters certainly deserve respect for their due role in framing constitutions and laws. Equally, these forums have a duty to afford respect and regard for all those segments of society that contribute to the multi-dimensional, fascinating complexity of Pakistani society.

(The writer is an author and a former senator and federal minister. He can be reached at: javedjabbar.2@gmail.com - The News)