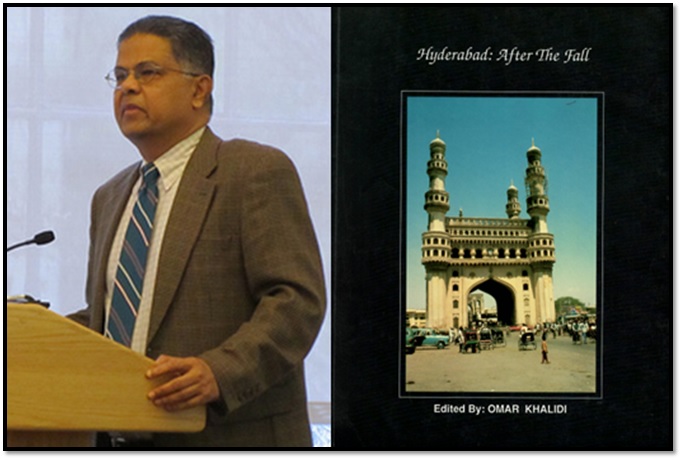

Book and Author

Omar Khalidi: Hyderabad — After the Fall

By Dr Ahmed S. Khan

September 13, 2024, marked the seventy-sixth anniversary of the invasion and annexation of Hyderabad state by India. Hyderabad: After the Fall, edited by Omar Khalidi — a collection of thirteen articles, essays, reprints, and extracts from books — provides a historical account and perspectives on the fall of the State of Hyderabad Deccan, and peoples’ experience right after Indian military invasion codename “Operation Polo,” which the Indian prime minister Nehru declared as “Police action.”

Omar Khalidi (b. Hyderabad, 1953 - d. Boston, 2010) was a prominent Indian Muslim scholar. He worked (1980-1983) at the King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. In 1983 he moved to the United States and joined the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) as a staff member, and later became a librarian for the Aga Khan Program at MIT libraries. His father Dr Abu Nasr M. Khalidi was a professor of history at Osmania University. Following his father’s academic tradition, Omar Khalidi produced a plethora of research articles and a number of scholarly books which include: Muslims in Indian Economy (2006), Muslims in the Deccan: A Historical Survey (2006), An Indian Passage to Europe: The Travels of Fath Nawaz Jang (2006), The British Residency in Hyderabad: An Outpost of the Raj (1779-1948), Between Muslim Nationalists and Nationalist Muslims: Maududi’s Thoughts on Indian Muslims (2004), Khaki and Ethnic Violence in India: Army, Police, and Paramilitary Forces During Communal Riots (2003), A Guide to Arabic, Persian, Turkish, and Urdu Manuscript Libraries in India(2003), Romance of the Golconda Diamonds (1999), Saqut-e-Hyderabad: Chashm Deed Aur Muasir TahreeroN Par Mushtamil Manzar Aur Pesh Manzar —edited with Dr. Muinuddin Aqil (1998), Indian Muslims Since Independence (1995), Islamic Literature in the Deccani Languages: Kannada, Marathi, & Telugu (1995), Memoirs of Sidney Cotton (1994), Shama-e-FaroozaN: Chand Ilmi Aur Adaabi ShakhshiyatooN Kay Halaat-e-Zindagi Aur Karnamay (1992), Memoirs of Cyril Jones: People, Society, and Railways in Hyderabad (1991), Factors in Muslim Electability to Lok Sabha (1991), Indian Muslims in North America (1990), African Diaspora in India: The Case of the Habashis of Deccan (1988), Deccan Under the Sultans, 1296-1724: A Bibliography of Monographic and Periodical Literature (1987), Hyderabad State Under the Nizams, 1724-1948: A Bibliography of Monographic and Periodical Literature (1985), and The British Residents at the Court of the Nizams of Hyderabad (1981).

In the introduction of the book, Omar Khalidi describing the fall of Hyderabad, observes: “It was ahead of many other regions in the spread of education, in offering equal justice, education and employment. Symbolic power may have been in the hands of Muslims, but economic power was widely distributed among the population. The state had evolved a way of life all its own, and promoted a pluralist culture. It was the most important area for the growth of Urdu literature in the subcontinent. When the Indian army marched in and replaced the Nizam's government, it deprived the state of a chance to work out a fair economic and political equation among its residents. As the British left, the Indian leaders engaged in hypocritical legalisms to distort the principle of accession offered to the princely states, with the result that the argument that was used to annex Kashmir was blatantly denied in the case of Hyderabad. Military power, of course, was in the hands of the Indians, and they used it to accomplish their goals while engaging in double-talk. While Gandhi and Nehru preached non-violence overseas, they had no qualms about their use of tanks and aerial bombing against poorly equipped, fledgling forces of Hyderabad. Backed by the military, Congress Party gangs engaged in mass killings, rape, and destruction of Muslim property all across the state. When it was all over, the Indian leaders made sure that no record of the atrocities became public knowledge. The death of as many as 200,000 in the so-called Police Action has remained unacknowledged…”

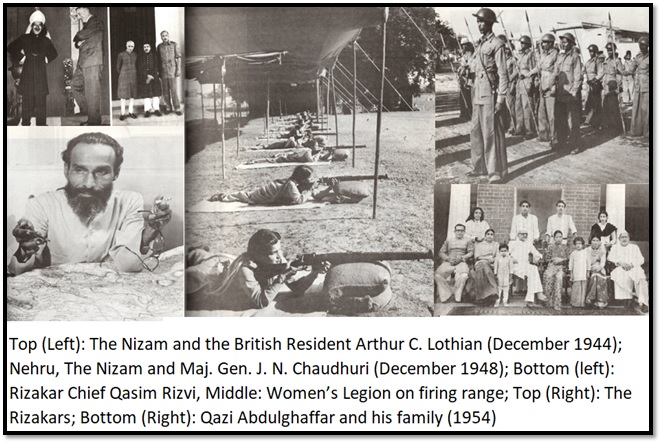

The book’s thirteen narratives provide a detailed account of pre- and post-1948 events. Professor Wilfred Cantwell Smith, in his essay “Hyderabad: Muslim Tragedy” provides a historical background to the events of 1947-48. Mir Laiq Ali, the last prime minister of the state of Hyderabad, in his narrative “The Five Day War” provides the details of the Indian military invasion, attempts to involve the UN Security Council, and the eventual surrender of t he Hyderabad armed forces. Zubaida Yazdani in her article “The End of an Era” describes the changes that took place at the highest levels of administration right after the military invasion. Pandit Sundarlal and Qazi Abdulghaffar — both veteran Congressmen — in their narrative titled “A Report on the Post-Operation Polo Massacres, Rape and Destruction or Seizure of Property in Hyderabad State” present their findings based on touring the outlying areas of Hyderabad after the arrival of the Indian army. Zahir Ahmad in his essay “Hyderabad on the Eve of the States Reorganization in 1956” paints a picture of the disorientation, uncertainty, and scramble for the transfer of official posts to Hyderabad city that characterized the Muslim society on the eve of the Indian states' reorganization and the break-up of the Hyderabad state on linguistic basis. Rashiduddin Khan's study sums up the major aspects of the economic problems of the Muslim community, especially of its middle class.

Theodore P. Wright, Jr's essay “Revival of the Majlis-i-Ittihadul Muslimin of Hyderabad” describes the emergence of a political pressure group in the new context of Andhra Pradesh. Ratna Naidu’s article “The Muslim Community in Bidar Since 1948” presents the problems of the Muslim community in Bidar, Karnataka, one of the districts affected the most by Operation Polo. Akbar S. Ahmed, in his essay “Muslim Society in South India: The Case for Hyderabad,” presents an overview of the Hyderabad Muslim society in the 1980s. Usama Khalidi, in his narrative “From Osmania to Birla Mandir: An Uneasy Journey” traces the emergence of the social history of Hyderabad, beginning with the dawn of modern times, roughly around 1917, to the 1980s labor migration to the Persian Gulf. And finally, Omar Khalidi in his article “The 1948 Military Operation and Its Aftermath: A Bibliographic Essay,” reviews the limited literature that is available in both Urdu and English on the post-Invasion of Hyderabad.

In the chapter “Hyderabad: Muslim Tragedy,” Wilfred Smith presents another perspective: “Under Razavi the Ihtihad elaborated the doctrine that Hyderabad was an Islamic State, the Nizam being the representative and symbol of a sovereignty that pertained in fact to the Muslim community, and which he exercised on their behalf. Every Hyderabadi Muslim, according to this view, became a participant, not only mystically but constitutionally, in the government of the State… the men at Westminster who framed the Independence Act of 1947, and the British Cabinet in general; d id definitely have in mind that Hyderabad and other States were to be free to choose any one of the three alternatives: joining India, joining Pakistan or becoming autonomous…The Nizam himself was rather put out that Great Britain was inaugurating a new age in India without consulting him. He apparently asked that he be allowed to keep Hyderabad within the empire as a separate dominion on its own, but this request was refused…. During 1948 India supplemented its political pressure with an economic blockade of Hyderabad state. There were also border raids, both from and into Hyderabad. These increased in frequency and depredation as the months went by. Both sides made detailed and fairly credible accusations against the other, and it seems probable that both were right in charging that the lower ranks, at least, of officialdom on each side were often implicated. The ideological war instigated the political groups — Congress on the India side, Razakar on the Hyderabad — to organi ze raiding bands.”

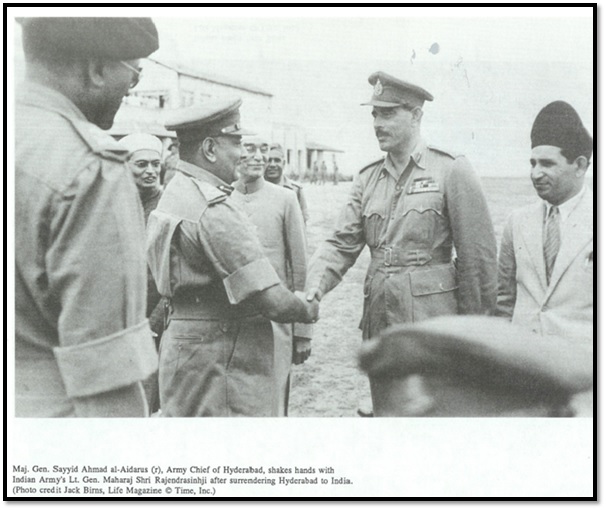

Describing the invasion, Wilfred Smith observes: “On September 13, 1948, the Indian army, moving on five fronts, invaded Hyderabad; and in less than a week the conquest was complete. The Nizam's army, apparently more of an exhibition than a fighting force, offered negligible opposition. There were relatively few battle casualties except amongst Razakars…off the battlefield, however, the Muslim community fell before a massive and brutal blow, the devastation of which left those who did survive reeling in bewildered fear. Thousands and thousands were slaughtered; many hundreds of thousands were uprooted. The instrument of their disaster was, of course, vengeance…estimates by responsible observers run as high as 200,000, and by some of the Muslims themselves still higher…The Nizam, when India invaded, accepted the resignation of his cabinet; and when the Indian army was nearing his capital, acknowledged its commander as head of his new government, with himself still the constitutional head of the state… However, it may have arisen, the Muslims' hybris, the overweening pride that led them to extravagant folly, brought them, as in a Greek drama, to disaster. That their fate was to some degree deserved, their suffering therefore self-inflicted, is integral to the tragedy.”

Mir Laiq Ali, the last prime minister of Hyderabad State, in his essay “In the “Five Day War” states: “It was in the early hours of the morning of the thirteenth of September (1948) that I was awakened by the shriek ringing of bedside telephone bell. This time it was on the direct line between the army Commander and myself. Even before I lifted the receiver I was sure it would be a report on the advance of the Indian armies - yes it was… The army Commander was telling me that within the last fifteen minutes, he had received messages from five different sectors of the advance of the Indian units on a mass scale. As he was talking to me, he had some more reports of intense bombing of the aerodromes at Bidar, Aurangabad and Warangal. He wanted to know what he should do. What did he expect me to say, I asked him, and then added ‘Of course ask your boys to resist the advance.’ ‘Very good, Sir’, he said and rang off…The pivot of the defense policy of Hyderabad was the great hope, and faith held in the United Nations Organization to stand by right against brute force. Timely and effective move by the Security Council which was then in session at Paris was the most vital factor. The Hyderabad delegation could reach only on the 13th September, to a great extent on the assumption that India’s offensive was to commence about a week later. Its departure from Karachi to some extent by the untimely death of the Quaid-i-Azam Jinnah. Moin Nawaz Jung had been warned before his departure that as a result of the Quaid's passing away, India might accelerate its plans…Eventually, the Delegation reached London late in the evening of the 13th. They left London by the first available plane on the 14th morning for Paris…The requisite documents were filed, and all formalities hurriedly concluded. The earliest that the meeting of the Security Council could be convened was on the afternoon of the 16th September…The invasion of Hyderabad by the armed forces of India had become the headline news of the press all over the world and the members of the Security Council of the United Nations, now in session at Paris, were fully seized of the situation through the press, their respective governments as well as the delegates both from Hyderabad and India. With rare exceptions, there was a wholesale condemnation of aggression committed by India and the public resentment both in the United Kingdom and the United States was particularly strong. Would all the pressure of public opinion from almost every country of the world prove strong enough to move the Security Council to take some speedy and effective action, was yet to be seen.”

Commenting further on the Security Council’s meeting, Mir Laiq Ali, states: “The much-awaited meeting of the Security Council was held at Paris on the afternoon of the 16th of September (1948) with the British delegate Sir Alexander Cadogan presiding. The primary issue before the meeting was whether the application of Hyderabad should be adopted on the agenda of the Council and considered. After some more discussions, the President called for the vote to adopt the application of Hyderabad on the agenda or to reject. The vote was 8 in favor of adoption on the agenda and 3 abstentions. The application was then formally adopted on the agenda and the President invited Moin Nawaz Jung, the leader of the Hyderabad delegation, to present his case. Moin Nawaz Jung very forcefully presented the case of Hyderabad at length and appealed to the Security Council to intervene and intervene at once to put a stop to the bloodshed and save his country from annihilation and make it possible to achieve lasting peace. It was now the turn of Ramaswamy Mudliar to speak on behalf of India. He had little ground to defend India’s position as an aggressor and laid stress only on the competence of Hyderabad to place its case before the Security Council. He promised to furnish documentary evidence to prove that Hyderabad had never been an independent state and as such had no status to approach the Security Council. The President wound up the meeting after listening to the two delegates, to give time to the members to study the situation carefully and fixed the next hearing for Monday, the 20th of September (1948). While the adoption by the Security Council of the application of Hyderabad on its agenda was a fundamental measure of success, the postponement of further consideration until the 20th of September presented a very gloomy aspect. The delegation from Hyderabad was fully conscious of the gravity of the situation and knew that it may be too late if the matter was deferred until the 20th….there was little of immediate value from the United Nations Security Council side. Here we were faced with the situation of the armored units of India reported within thirty miles of the capital marching along a totally undefended road… Early next morning, a convoy of military vehicles surrounded my house, but no one entered it. We waited and waited till it was daylight and the sun had risen high. Apparently, the unit was in wireless communication with its Head Quarters. Finally, the convoy of vehicles left in the same formation as they had come. We waited and waited but nothing further happened. Perhaps the session of the Security Council had something to do with it. Hours rolled into days, days into months and months into years. There was little if anything happened to me or come to my knowledge worth recording. And, then one day, a Providential E-S-C-A-P-E!”

Clyde Eagleton in his essay “In Case of Hyderabad Before the Security Council,” observes: “On the agenda of the Security Council, and regularly listed by the Secretary-General among the 'matters of which the Security Council is seized’ is the item ‘Question of Hyderabad.’ No action has yet been taken by the Security Council on this item, further than keeping it on the agenda; the case has been presented but not discussed. Various interesting questions of international law and of the constitutional law of the United Nations are raised by this situation, which is thus far the worst failure of the United Nations. The complaint of Hyderabad was presented in a cablegram dated. August 21, 1948, addressed to the President of the Security Council, which read as follows: The Government of Hyderabad in reliance on Article 35, paragraph 2, of the Charter of the United Nations, requests you to bring to the attention of the Security Council the grave dispute which has arisen between Hyderabad and India, and which, unless settled in accordance with international law and justice, is likely to endanger the maintenance of international peace and security. Hyderabad has been exposed in recent months to violent intimidation, to threats of invasion, and to crippling economic blockade which has inflicted cruel hardship upon the people of Hyderabad and which is intended to coerce it into a renunciation of its independence. The frontiers have been forcibly violated and Hyderabad villages have been occupied by Indian troops. The action of India threatens the existence of Hyderabad, the peace of the Indian and entire Asiatic Continent, and the principles of the United Nations. The Government of Hyderabad is collecting and will shortly present to the Security Council abundant documentary evidence substantiating the present complaint. Hyderabad, a State not a Member of the United Nations, accepts for the purposes of the dispute the obligations of pacific settlement provided in the Charter of the United Nations…”

Reflecting on the lack of action by the security council, Clyde Eagleton, further states: “What is involved here is a question of fundamental importance to the United Nations, a question upon which the American Society of International Law has appointed a committee to report to its next meeting. This question is whether the United Nations is to be a constitutional system or not. Thus far, its trend has been away from law; the Security Council (and the General Assembly as well) has overridden the restrictions set by the Charter where it has desired to take an action, and has disregarded both its obligations under, and the principles of, the Charter when it did not desire to take action. This problem is now beginning to be recognized and debated; it obviously cannot be discussed here. It is in this connection that the case of Hyderabad deserves study by those who are interested in achieving a system of international law and order in the world.”

Hyderabad: After the Fall , provides a historical account of pre- and post- 1948 events related to the invasion and annexation of Hyderabad State by India, and the resulting impact on the Muslim community. It is a required reading for all students of history as well as for general readers.

Back to Pakistanlink Homepage