Book & Author

Coleman Barks: The Essential Rumi

By Dr Ahmed S. Khan

This being human is a guest house

Every morning a new arrival

A joy, a depression, a meanness,

some momentary awareness comes

as an unexpected visitor…

—Rumi

December 17, 2024, marked the 751st death anniversary of Jalal-ud-Din Muhammad Rumi aka Maulana (Our Master) Rumi, the most popular Sufi poet in the United States. His message of love, peace, and harmony via deeply spiritual poems has captivated millions, making him the best-selling poet in the United States for many years.

The Essential Rumi by Coleman Barks presents an English translation of a collection of poems by Rumi. The book, consisting of 28 sections, captures Rumi's deep spirituality and explores themes like love, longing, and the divine. The author’s interpretations aim to capture the essence and emotional appeal of Rumi’s poetry, bringing it to a global audience and enabling them to foster a deeper appreciation of the mystic’s timeless message of love, peace, and wisdom.

The titles of the 28 sections of the book are: 1.Tavern: Whoever brought me here will have to take me home, 2. Bewilderment: I have five things to say, 3. Emptiness and silence: Night air, 4. Spring giddiness: Stand in the wake of this chattering and grow airy, 5. Feeling separation: Don't come near me, 6. Controlling the desire-body: How did you kill your rooster, Husam?, 7. Sohbet: Meetings on the riverbank, 8. Being a lover: Sunrise ruby, 9. Pickaxe: Getting to the treasure beneath the foundation, 10. Art as flirtation with surrender: Wanting new silk harp strings, 11. Union: Gnats inside the wind, 12. Sheikh: I have such a teacher, 13. Recognizing elegance: Your reasonable father, 14. Howling necessity: Cry out in your weakness, 15. Teaching stories: How the unseen world works, 16. Rough metaphors: More teaching stories, 17. Solomon poems: Far mosque, 18. Three fish: Gamble everything for love, 19. Jesus poems: Population of the world, 20. In Baghdad, dreaming of Cairo: More teaching stories, 21. Beginning and end: Stories that frame the Mathnawi, 22. Green ears everywhere: Children running through, 23. Being woven: Communal practice, 24. Wished-for song: Secret practices, 25. Majesty: This we have now, 26. Evolutionary intelligence: Say I am you, 27. Turn: Dance in your blood, and 28. Note on these translations and a few recipes.

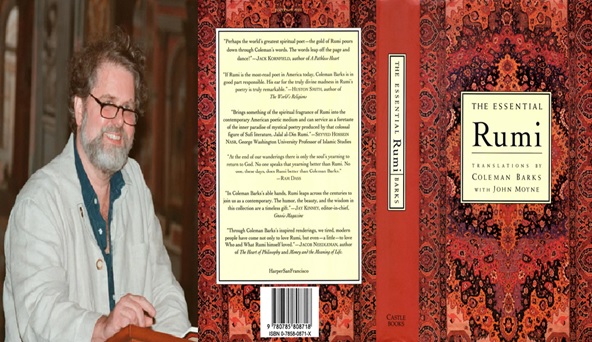

Coleman Bryan Barks (b. 1937) is a poet, translator, and a former literature faculty member at the University of Georgia. He is known for his popular interpretations of Rumi’s poetry via his books — The Essential Rumi (1995), The Book of Love (2003), and A Year with Rumi (2006). He has played a pivotal role in popularizing Rumi among the English-speaking audience.

In the 20 th century, prominent scholars — R.A. Nicholson, A. J Arberry, and Annemarie Schimmel — translated Rumi’s work into English and enabled readers in the West to enjoy the message of Rumi. Barks, by translating and interpreting Rumi’s work into American verse, played a pivotal role in making Rumi the best-selling poet in the United States. The mastery of Barks craft is evident from the translation of the following poem titled “The Guest House:”

This being human is a guest house.

Every morning a new arrival.

A joy, a depression, a meanness,

some momentary awareness comes

as an unexpected visitor.

Welcome and entertain them all!

Even if they’re a crowd of sorrows,

who violently sweep your house

empty of its furniture,

still, treat each guest honorably.

He may be clearing you out

for some new delight.

The dark thought, the shame, the malice,

meet them at the door laughing,

and invite them in.

Be grateful for whoever comes,

because each has been sent

as a guide from beyond.

Reflecting on how the author got involved in translating Rumi, he observes: “My academic training, at Berkley and Chapel Hill, was in American and twentieth-century literature. I had never even heard Rumi’s name until 1976, when Robert Bly handed me a copy of A.J Arberry’s translations, saying, ‘These poems need to be released from their cages.’ How any translator chooses to work on one poet, and not on others, is a mysterious thing…I felt drawn immediately to the spaciousness and longing in Rumi’s poetry. I began to explore this new world, rephrasing Arberry’s English. I sent some of my early attempts to a friend who was teaching law at Rutgers-Camden. He, inexplicably, read them to his class. A young law student came afterward, asked for my address, and started writing, urging me to come meet his teacher in Philadelphia. When I finally did walk into the room where Sri Lankan saint Bawa Muhaiyaddeen sat on his bed talking to a small group, I realized that I had met this man in a dream the year before. I can’t explain such an event, nor can I deny that it did happen. Bawa told me to continue with the Rumi work; ‘It has to be done.’ But he cautioned, ‘If you work on the words of a gnani, you must become a gnani,’ a master. I did not become one of those, but for nine years, for four or five intervals during each year, I was in the presence of one. Rumi says, ‘Mind does its fine-tuning hair-splitting / but no craft or art begins / or can continue without a master / giving wisdom into it. I would have little notion of what Rumi’s poetry is about or what it came out of if I were not connected to this sufi sheikh. Though it’s not necessary to use the word sufi. The work Bawa did and does with me is beyond Religion. ‘Love is the religion, and the universe is the book.’ Working on Rumi’s poetry deepens the inner companionship.”

Introducing Rumi’s background, the author observes: “Persians and Afghanis call Rumi ‘Jelaluddin Balkhi.’ He was born September 30, 1207, in Balkh, Afghanistan, which was then part of the Persian empire. The name Rumi means ‘from Roman Anatolia.’ He was not known by that name, of course, until after his family, fleeing the threat of the invading Mongol armies, emigrated to Konya, Turkey, sometime between 1215 and 1220. His father, Bahauddin Walad, was a theologian and jurist and a mystic of uncertain lineage… Rumi was instructed in his father's secret inner life by a former student of his father, Burhanuddin Mahaqqiq. Burhan and Rumi also studied Sanai and Attar. At his father's death Rumi took over the position of sheikh in the dervish learning community in Konya.”

Reflecting on Rumi’s meeting with his spiritual mentor, the author notes: “His life seems to have been a fairly normal one for a religious scholar — teaching, meditating, helping the poor — until in the late fall of 1244 when he met a stranger who put a question to him. That stranger was the wandering dervish, Shams of Tabriz, who had traveled throughout the Middle East searching and praying for someone who could ‘endure my company.’ A voice came, ‘What will you give in return?’ ‘My head!’ ‘The one you seek is Jelaluddin of Konya.’ The question Shams spoke made the learned professor faint to the ground. We cannot be entirely certain of the question, but according to the most reliable account Shams asked who was greater, Muhammad or Bestami, for Bestami had said, ‘How great is my glory,’ whereas Muhammad had acknowledged in his prayer to God, ‘We do not know You as we should.’”

Elaborating further on Rumi’s meeting with Shams, the author states: “Rumi heard the depth out of which the question came and fell to the ground. He was finally able to answer that Muhammad was greater, because Bestami had taken one gulp of the divine and stopped there, whereas for Muhammad the way was always unfolding. There are various versions of this encounter, but whatever the facts, Shams and Rumi became inseparable. Their friendship is one of the mysteries. They spent months together without any human needs, transported into a region of pure conversation. This ecstatic connection caused difficulties in the religious community. Rumi's students felt neglected. Sensing the trouble, Shams disappeared as suddenly as he had appeared.”

Commenting on the disappearance of Shams and Rumi’s transformation into a mystic, the author observes: “Annemarie Schimmel, a scholar immersed for forty years in the works of Rumi, thinks that it was at this first disappearance that Rumi began the transformation into a mystical artist. ‘He turned into a poet, began to listen to music, and sang, whirling around, hour after hour.’ Word came that Shams was in Damascus. Rumi sent his son, Sultan Velad, to Syria to bring his Friend back to Konya. When Rumi and Shams met for the second time, they fell at each other's feet…Shams stayed in Rumi's home and was married to a young girl who had been brought up in the family. Again the long mystical conversation (sobbet) began, and again the jealousies grew. On the night of December 5, 1248, as Rumi and Shams were talking, Shams was called to the back door. He went out, never to be seen again. Most likely, he was murdered with the connivance of Rumi's son, Allaedin; if so, Shams indeed gave his head for the privilege of mystical Friendship.”

Commenting on Rumi’s life after the disappearance of Shams, the author notes: “The mystery of the Friend's absence covered Rumi's world. He himself went out searching for Shams and journeyed again to Damascus. It was there that he realized, why should I seek? I am the same as he. His essence speaks through me. I have been looking for myself! The union became complete. There was full fana, annihilation in the Friend. Shams was writing the poems. Rumi called the huge collection of his odes and quatrains "The Works of Shams of Tabriz.”

Reflecting on Rumi’s post-Shams life, the author observes: “After Shams's death and Rumi's merging with him, another companion was found, Saladin Zarkub, the goldsmith. Saladin became the Friend to whom Rumi addressed his poems, not so fiercely as to Shams, but with quiet tenderness. When Saladin died, Husam Chlebi, Rumi's scribe and favorite student, assumed this role. Rumi claimed that Husam was the source, the one who understood the vast, secret order of the Mathnawi, that great work that shifts so fantastically from theory to folklore to jokes to ecstatic poetry. For the last twelve years of his life, Rumi dictated the six volumes of this master-work to Husam. He died on December 17, 1273.”

Expounding on the organization of the book, the author notes: “The design of this book is meant to confuse scholars who would divide Rumi’a poetry into the accepted categories: the quatrains (rubaiyat) and odes (ghazals) of the Divan, the six books of the Mathnawi, the discourses, the letters, and the almost unknown Six Sermons. The mind wants categories, but Rumi's creativity was a continuous fountaining from beyond forms and the mind, or as the Sufis say, from a mind within the mind, the qalb, which is a great compassionate generosity. The twenty-seven divisions here are faint and playful palimpsests spread over Rumi's imagination. Poems easily splash over, slide from one overlay to another. The unity behind, La'illaha il'Allahu (‘there's no reality but God; there is only God’), is the one substance the other subheadings float within at various depths. If one actually selected an ‘essential’ Rumi, it would be the zikr, the remembering that everything is God. Likewise, the titles of the poems are whimsical.”

Elaborating further on the structure and style of Rumi's poetry, the author states: “Rumi’s individual poems in Persian have no titles. His collection of quatrains and odes is called The Works of Shams of Tabriz (Divani Shamsi Tabriz). The six books of poetry he dictated to his scribe, Husam Chelebi, are simply titled Spiritual Couplets (Mathnawi), or sometimes he refers to them as The Book of Husam. The wonderfully goofy title of the discourses, In It What's in It (Fihi Ma Fihi), may mean ‘what's in the Mathnawi is in this too,’ or it may be the kind of hands-thrown-up gesture it sounds like. All of which makes the point that these poems are not monumental in the Western sense of memorializing moments; they are not discrete entities but a fluid, continuously self-revising, self-interrupting medium. They are not so much about anything as spoken from within something. Call it enlightenment, ecstatic love, spirit, soul, truth, the ocean of ilm (divine luminous wisdom), or the covenant of alast (the original agreement with God). Names do not matter. Some resonance of the ocean resides in everyone. Rumi's poetry can be felt as a salt breeze from that, traveling inland. These poems were created, not in packets and batches of art, but as part of a constant, practical, and mysterious discourse Rumi was having with a dervish learning community. The focus changed from stern to ecstatic, from everyday to esoteric, as the needs of the group arose. Poetry and music and movement were parts of that communal and secretly individual work of opening hearts and exploring the mystery of union with the divine. The form of this collection means to honor the variety and simultaneity of that mystical union.”

The Essential Rumi by Coleman Barks offers a profound exploration of the human experience through the lens of Rumi's timeless wisdom. Barks has done a wonderful job of translating Rumi’s work into American verse – he has succeeded in keeping the essence of Rumi's message in the translated work. The book is a joyful journey into the heart of spirituality, love, peace, wisdom, and self-discovery.