Photo Wikimedia

A City Triumphant

By M. Majid Ali

New Jersey

The following series of events transpired on a June day in Karachi. They provide critical insight into the lives of its common citizens as they go about their daily lives, the challenges they face, and the small victories they achieve against overwhelming odds. These are their stories and if the ensuing rendition appears to maintain a singular bent then so be it for it resets a historical imbalance.

The gathering roar of the oncoming 8.32 pm subway train beneath New York City’s Times Square at the 42nd Street subway station fails to drown out the timeless beat of the Congo drums being played by the platform ensemble. In between trains, commuters stroll by dropping coins in a can while others pause to listen to the warm resonant drumbeat that originated amongst the thousands of slaves brought from the African Congo in the 17th and 18th centuries. Such was the astonishing draw of these drums that it prompted the State of South Carolina in 1740 to enact the Negro Act which, while banning education for slaves, also prohibited them from playing these instruments due to fear of organization, assembly and insurrection.

Seven thousand miles east of New York, an orange dawn is breaking over the northern suburb of Malir in Karachi. Falak, an auto-rickshaw operator, scrambles out of bed to begin his day. He dashes through a modest breakfast of bread dipped in tea which gets him through most of the morning. He recalls a time when his wife would also fry him an egg but with inflation driving prices past Rs 420/dozen, they simply did not fit the budget. As he walks out to start his day at 6 am he glances at his four children who are still asleep, just as they were when he had returned from work the night before at 2 am.

Photo Getty Images

Falak is good-natured and has built an established clientele. Uzma Baji, an elderly teacher, is the first one to be dropped off at her school in Gulistan e Johar followed by a pair of siblings in Saudabad to the QBH school. Having dispensed with his regular riders he begins to pick up a diverse set of patrons on the streets of Karachi till the sun rises high above him and if he is lucky to be close enough to Jinnah Square in Liaquat Market he hustles over to his favorite Rehmania lunch cart for a plate of chicken palau which he enjoys while seated inside the shade of his vehicle.

The life of a rickshaw operator endures the multiple challenges of impaired roads, uneven business cycles, costly repairs, weekly oil changes, law and order situations, and civil disturbances that can shut down operations for days. The ridership itself is subjected to all kinds of near-impacts and concussions on Karachi’s roads. When it rains, water accumulates everywhere reaching spectacle proportions in Model Colony. Half-hour trips begin to take three hours. And Falak never really knows who is riding in the back seat. Quaidabad, Orangi Town and Layari remain difficult zones.

Nevertheless, on a good day that starts at 6 am and usually ends after 1 am Falak emerges with just enough cash receipts to put a meal on the table for the eight people in the house that he shares with his extended family. Today is such a day. Ridership has been steady, and things are looking up. He is near Darul Shifa Hospital when a customer hails him to go to Saddar. The rickshaw is turned around and they begin to move south in the direction of Shahrah e Faisal.

They say “the truth shall set you free.” It is now mid-morning and back in Malir at the TCF School, Khokrapar campus, the school is holding its annual entrance exams. An interesting spectacle is unfolding as a group of ten children accompanied by parents disembark from motorcycles and rikshaws and gather at the entrance. The parents had heard a few months ago about the quality education, decent facilities, playgrounds, and low fees of TCF Schools and were interested in getting their children admitted. Working under the guidance of young volunteer tutors, the children had spent the past few months preparing for these exams.

There is excitable chatter as the children gather in the courtyard bordered by a playground on one side and a canteen on the other. The Primary section is on the lower floors while the secondary section is elevated on the higher floors with the principal’s office in between. The classrooms have adequate furniture and computer labs. Amazingly the building is solarized. The Admission Coordinator leads the children through the school to an examination room while the parents are asked to wait near the principal’s office. Testing commences and the students put pencil to paper while the parents fall into silent prayer.

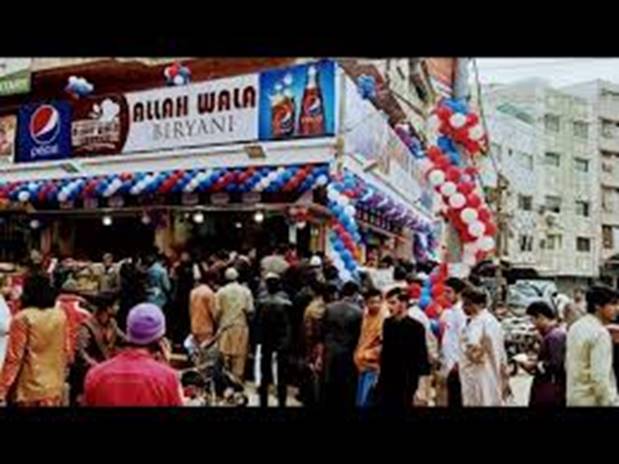

Meanwhile, lunchtime arrives in Karachi as the sun travels directly overhead. Two friends seated in a blue Toyota are headed over to the Allah Walla Biryani branch on Tipu Sultan Road. The service road is crowded, and they park in front of the modest but busy establishment. A waiter approaches and they order the standard chicken biryani and a specific cola brand which they are told is unavailable but which the waiter promises to obtain from the neighboring store.

Eight minutes later the waiter returns and serves up two steaming plates of biryani filled to the brim that could feed four people instead of two along with their favorite cola drinks. Hungry, the friends dive right into their plates relishing the taste in every bite. They then notice an elderly man watching them about fifteen feet from the car so decide to give one plate away to him. He gratefully places the biryani container inside his knapsack and quickly departs.

When the attendant returns to check on them after a few minutes the friends chat him up. They learn his name is Nasir Shah and he is originally from Mirpur Khas in

Sindh. That his work ethic approaches heroic proportions as he talks about his twelve-hour shift followed by a forty-five-minute bus ride at 2am to the one room rental in Gulistan Johar that he shares with his wife and three children and where he is invariably greeted by the darkness of perennial load-shedding is not lost on the two friends.

The bill is paid and since much has been written about the chicken qorma at Allah Wala Biryani the friends order some to take home. Their business concluded, they hand the attendant a Rs 500 tip but he hesitates and looks around fearful of being reprimanded by watchful supervisors. They have to force the bill inside his front pocket and he finally accepts it with a grateful countenance. The friends back out their Toyota in the rushing traffic behind them, somehow miraculously turn it around and speed off towards the JDC Free Lab on MA Jinnah Road near Quaid’s Mazar.

Twenty minutes west of Tipu Sultan Road the fire inside the tandoor at the Burns Road hotel has reached 480 degrees Celsius. Gul Ahmed sits crouched two feet away from the pit and every few seconds plucks a dough ball from a massive pile, rolls it flat in an oval shape on the rolling base, and with bare hands presses it inside the walls of the burning Tandoor. At any given time, he has eight to nine nans suspended over the fire in the tandoor. Every ninety seconds he extends two long metal spatulas to retrieve nans from the tandoor and deposit them in a basket. Waiters appear every few seconds to gather their orders.

Ceaselessly, diligently for three hours and without the benefit of a working fan or cold-water Gul Ahmad’s limbs operate like the unfailing pistons of a combustion engine as he churns out dozens of nans. Peak summer is also peak load-shedding season and today has been a scorcher. The plastic water bottle two feet away from the tandoor appears to bubble. But Gul does not seem to perspire. There are no wrinkles on his forehead. External validation is neither desired nor sought. Pashtun pride alone drives the efficiency of his private trade.

Meanwhile, Falak is dropping a passenger at one of the Hill Park Hospital clinics where long-time Karachi physician Dr Abbas occasionally provides free services to qualifying patients. After ushering the patient inside he heads back out on Shaheed e Millat Road and is bearing north towards Malir on Shahrah Faisal when he receives a pickup call from a family finishing an event in Gulshane Maymar near Super Highway. As Falak arrives the family embarks with the elders in the back and a young boy who shares the front seat with Falak. As they get on the main road a motorcycle with two men appears alongside the rikshaw. A gun is pointed at Falak and the young boy in the front seat to get them to stop.

Falak is a seasoned transport operator who has seen the best and worst of the city. He abruptly slows down giving the impression that he is coming to a stop. Seeing the rikshaw slow down the men are hasty to disembark from their motorcycle. Falak sees his opportunity and quickly accelerates brushing past the parked bike and loses the disembarked bikers in the traffic behind him. A few minutes later he pulls the rikshaw into a wedding hall parking lot as his passengers are in utter shock. A crowd gathers to provide water and assistance. Falak then dials the police and is able to arrange an escort part of the way back to Malir.

Late afternoon and back at the TCF Khokrapar school in Malir, the children accompanied by their parents have reconvened in the courtyard to learn about their admissions results. They are asked to file back to the testing area while their parents wait. Anxious eyes follow the principal as she walks in to announce the results. Her dawning smile converts guarded apprehension on the waiting faces to buoyant optimism. Everyone has passed. The young children are ecstatic and sprint up and down the corridor as they are told they can start attending the TCF school. The parents and the volunteer tutors who spent weeks preparing the children for the admission exams look on with pride and delight.

Seema is the youngest of the students. Her mother had sacrificed particularly hard by working an extra job as a maid in a posh section of Malir to get her daughter ready for her TCF admission test. As the successful results are announced Seema races towards her mother, totters forward, slips, somehow uprights herself, then lands in her mother’s lap and squeals in delight, “Thank you Mamma!”

Seven thousand miles away beneath the streets of Manhattan’s Times Square and inside the 42nd Street subway station the Congo drums are beating louder.

The truth shall set me free!

(The author is a freelance writer and a former resident of Karachi)

=======================================

Back to Pakistanlink Homepage