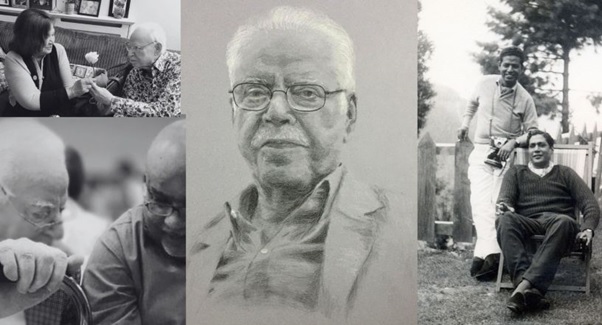

Anis and Haroon, London, 2019 – photo by Muzaffar Husain; Dr Haroon and Dr Wasif, Karachi 2018; ‘Tribute to Dr Haroon,’ by Sharjil Baloch, charcoal on paper, 2024; Dr Haroon and Dr M. Sarwar, Nathiagali, 1960s. Collage by Regina Johnson / Sapan News

Dr Haroon Ahmed: A Healer, Comrade, and Peacemonger across South Asia

By Beena Sarwar

Boston, MA

Dr Haroon Ahmed was to be one of the key speakers at the South Asia Peace Action Network, or Sapan, seminar on the last Sunday of June 2021. The seminar, titled ‘Neighbors in Peace and Health’ focused on public health as a basic human right, and I was excited about having Haroon Cha, as I called him, on the same platform as another public health giant, Dr Zafrullah Chowdhury, from Bangladesh.

Sadly, Dr Haroon suffered a stroke just a week earlier and was unable to join. He never really recovered, the decline slowed by his indomitable spirit and will and unflaggingly good nature. He and his wife Anis had both been at the online meeting on the last Sunday of March 2021, that launched Sapan just months earlier.

Dr Chowdhury, who had joined Sapan volunteers on a planning call the previous week – while getting dialysis from his hospital bed in Dhaka — passed away on 11 April 2023, less than two years after the June online seminar.

Our fractured region

It is a tragedy of our fractured region that we don’t know about each other’s heroes. Having never met Dr Chowdhury in person, I and my colleagues at Sapan felt privileged to have got to know about him and his work, thanks to our regional network of ‘peacemongers’ as I call our constituents.

The loss of Dr Haroon, who passed away in Karachi on 3 April 2025, was more personal. He was like a ‘chacha’ (father’s brother) for us. Our only ‘real’ chacha, my father’s first cousin, lives in Allahabad, but we’ve hardly ever met him, kept apart by the intractable visa regime between Pakistan and India.

When you meet a long-lost relative, you recognize family characteristics and mannerisms. There is love and familiarity. You can also feel love and familiarity for someone you are not related to by blood but who you have been close to all your life. Someone who has pulled your cheeks when you were a child, and your daughter’s cheeks when she was little, whose affectionate shoulder slaps later landed hard enough to elicit an “ouch!”

Even after the stroke, his love and affection shone through that hand squeeze and his smile. He participated diligently in regular speech and physiotherapy sessions until more strokes made it impossible. The last time I saw him was about a month ago. He held my hand, asking about my mother, Zakia. There was a visible deterioration since I last saw him just a few months earlier. Only Anis Aunty, reclining on the bed next to him — her constant spot since his illness — could understand what he was trying to say.

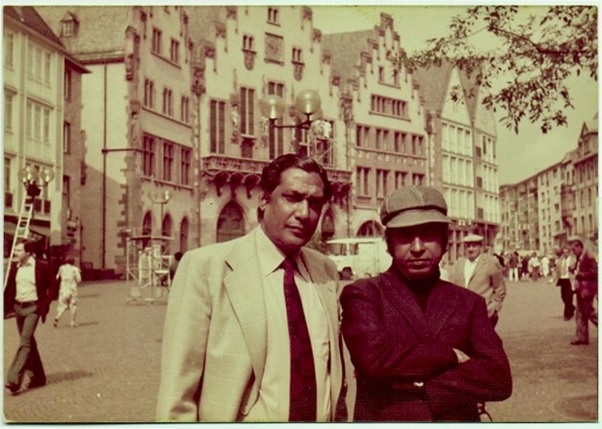

A rare trip together: Dr Haroon and Dr M. Sarwar, UK, 1970s - Photo Family archives

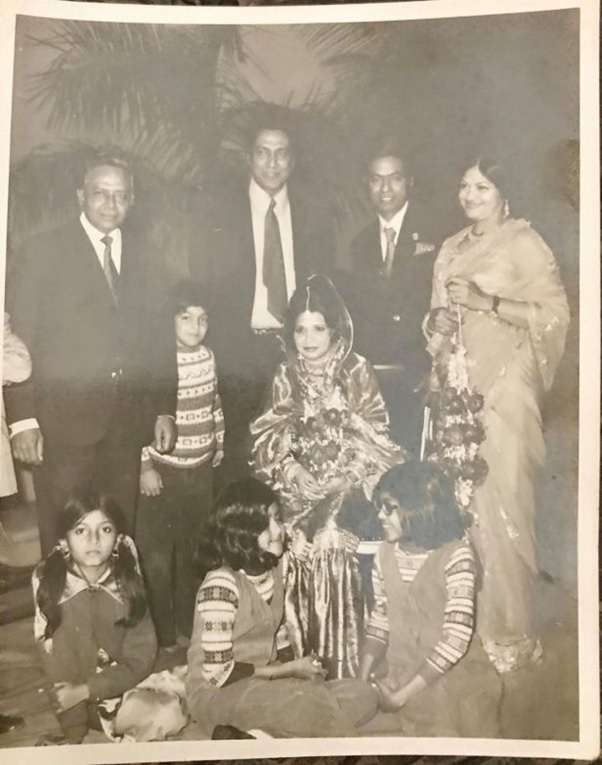

Anis and Dr Haroon wedding, Karachi, 1974: (from left, standing) Dr Sharif ‘Laali’, Dr M. Sarwar, Dr Haroon, Zakia Sarwar; (children, from left) Uzma Ahmed, Salman, Sehba, and Beena Sarwar - Photo Family archives.

Married in 1974, they were devoted to each other. Some 16 years younger, Anis (nee Taffazal) had been a student activist at university. She was a journalist and political activist when they met in the early 1970s, soft-spoken but with an iron will.

When Haroon’s mother went to ask for her hand in marriage, he made it clear he wanted no dowry: “Just her, and her books.”

I never heard them argue or raise their voice at each other. There must have been disagreements, as there are with any couple. But here, these would be sorted out in a civil and gentle manner, their relationship marked by mutual trust and respect.

They were comrades in the ongoing struggle for human rights and dignity. A devoted wife and mother, Anis also had the full freedom to develop as one of the country’s foremost feminist and human rights activists, including frequent travels to Islamabad during her stint as Chairperson, the National Commission on the Status of Women, Pakistan, January 2009 to March 2012.

From left: Salima Hashmi, Zakia Sarwar, Sheen Farrukh, Sikandar Zaman, Dr M. Sarwar, Firdous Hyder, Anis Haroon, Usha Zuberi, Dr Haroon Ahmed, Karachi 1980s - Photo Family archives

Haroon adored my father, like other friends looking up to and acknowledging Dr Sarwar as their ‘leader’ long after he withdrew from public life. Regular political discussions lasting over late-night dinners were a regular feature at our place – my father disliked going out, only occasionally making exceptions for close friends like Haroon and Anis, Saleem Asmi, Hilda and Mazhar Saeed and a few others.

Student movement

In 1949, Haroon and my father Sarwar were among the founders of the Democratic Students Federation. This developed into Pakistan’s first nationwide student movement. My father had skipped exams in his final year at the students’ behest in order to continue his student activism.

Dr Haroon obtained his MBBS degree, which he topped, in 1954. He had earlier represented the DSF at a leftist youth conference in Hungary and while abroad, also visited the then Soviet Union. In the months he was away, he also spread awareness about the student political activity in Pakistan. By the time he returned, DSF had been banned and many of his comrades were behind bars, including my father.

He retained his lifelong commitment to progressive thought and social change, sharing a comradeship with my father that lasted a lifetime. Active in the Pakistan Medical Association, they co-founded the Pakistan Medical Gazette in the 1980s, at the peak of Gen Ziaul Haq’s oppressive military regime. Haroon persuaded Sarwar to start contributing a weekly column to the Gazette, and my father wrote sharp political commentaries in the guise of conversations and satire. The message hit the mark while not getting the publication shut down. A balancing act we need to re-learn all over again today.

If Haroon had not been a doctor, he would have been a photographer. He avidly recorded precious moments with icons like the poets Faiz and Faraz, historian Syed Sibte Hasan, and others at their social gatherings, besides personal moments like my parents as newlyweds on the beach in a rare show of public affection.

One photo features a curly-haired child holding a book from his extensive collection — my then 4-year-old daughter at their place after she insisted on going home with him and Anis Aunty one evening. They took her out for ice cream then she kept them up late into the night. From all accounts, a fun experience.

As I grew up and began being part of activist movements, my life with Haroon and Anis intersected independently from my parents. They were associated with the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan spearheaded by the human rights advocate Asma Jahangir, that I became involved with after moving to Lahore in 1988.

A foundational leader

We were together at the first formal meeting of the Pakistan-India People’s Forum for Peace and Democracy in Delhi, and in the Pakistan-India anti-nuclear arms campaign in 1998. Dr Haroon was also on the founding team of the Pakistan chapter of the International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War, which he initially presided over. He was thrilled when I met IPPNW’s co-founder Dr Barnard Lown in the Boston area.

Later, he was also a moving force behind the Forum for Secular Pakistan, registered in 2012; meetings often took place at his clinic near Teen Talwar, Karachi. Another driving spirit behind that initiative was Iqbal Alavi, one of the last to be imprisoned in the dragnet of 1954.

While I knew of Dr Haroon’s role as a pioneering psychiatrist in Pakistan, I learnt more from his former student Dr Syed Ali Wasif, current President of the Pakistan Association for Mental Health that Dr Haroon established in 1965. This was a “milestone that enabled him to extend care to those most in need.”

Dr Haroon had pursued advanced psychiatric training at Maudsley Hospital, UK, – the ‘Mecca’ of Psychiatry – where he trained and worked under the supervision of the legendary psychiatrist Sir Aubrey Lewis. A “dedicated mentor and a tireless advocate for mental health,” he co-founded the Pakistan Psychiatric Society in 1972 and was a senior psychiatrist at Jinnah Hospital’s Ward 20.

“Mental Health at the Doorstep of the Community” was the slogan with which Dr Haroon championed the new concept of community psychiatry.

In 1995, PAMH launched the Institute of Behavioral Sciences, envisaged as a premier psychiatric facility and non-profit organization offering state-of-the-art treatment and academic training in Karachi.

It led to the only disagreement between my father and Dr Haroon that I know of. Dr Sarwar and other friends mistrusted the significant donations raised by sources like the nuclear scientist Dr Abdul Qadeer Khan. Time proved them right as Dr Khan took over the institute, which was named Dr A. Q. Khan Center – Institute of Behavioral Sciences.

Saddened but sanguine as ever, Dr Haroon continued his work in other ways. Recognizing the outdated nature of Pakistan’s psychiatric legislation, he spearheaded efforts to replace the archaic Lunacy Act of 1912, a significant contribution to mental health law reform.

“His perseverance led to the passage of the Sindh Mental Health Act of 2013, the first law in Pakistan to provide safeguards for individuals with psychiatric illnesses, including those accused under blasphemy laws. His relentless advocacy ensured its enactment, leaving an indelible mark on the country’s legal framework.”

Tributes pouring in for Dr Haroon from across Pakistan and India, and the crowds of people showing up at his and Anis Aunty’s house in Karachi are a testimony to the many lives he touched. May his legacy live on, reflected in the work taken forward by mental health practitioners, human rights activists, feminists and peacemongers.

( Beena Sarwar is a journalist from Pakistan currently based in Boston. Personal Political is her longtime occasional column. She is the founder and editor of Sapan News. Email: beena@sapannews.com.) - Sapan News