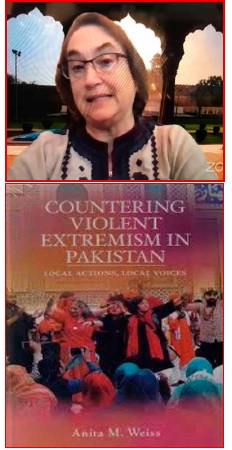

Dr Anita Weiss Lauds Pakistani Civil Society in Combating Violent Extremism

By Elaine Pasquini

Washington, DC: On December 13, the Wilson Center, together with South Asia Democracy Watch, hosted Dr Anita Weiss to present the 2021 Asma Jahangir Memorial Lecture, a series honoring the late Pakistani leading human rights activist Asma Jahangir, who passed away in 2018.

Weiss, professor of International and Global Studies at the University of Oregon, spoke on the subject of her new book, Countering Violent Extremism in Pakistan: Local Actions, Local Voices.

The professor, who first visited Pakistan in 1978 and has returned almost annually since 1985, has traveled extensively throughout the country in both urban and rural areas.

She was inspired to write her eighth book, Countering Violent Extremism in Pakistan, following the bombing of the Army Public School in Peshawar on December 16, 2014, which killed over 140 people. “The attack on the school was a pivotal moment in Pakistan’s consciousness about terrorism,” Weiss said. “It really was a very provocative moment resulting in an overwhelming outcry that something absolutely had to be done.”

Following this horrendous event, she noted acts of “reclaiming identity and authenticity,” she said. “This was nationalism – what I was writing about. This is nationalism in its truest form – people all over Pakistan asserting they want their cultural identity back, asserting they want their society intact and to throw off the bondages of hatred, violence and fear that at least for a while seemed to break out at any time in Pakistan.”

Since then, individuals, NGOs and local communities have been engaging in various kinds of actions to lessen the violence, and also recapture indigenous cultural identity.

The Walls of Karachi, for example, an art project organized by the local municipality of Karachi, evoke powerful images that speak to cultural cohesiveness. The bus stops created by the Lahore Biennale project provide workers traveling under the harsh summer sun or bitter winter rains with the sense that “someone in their community cares to give them shelter,” Weiss said. “Religious leaders are actively engaged in creating communities to talk with each other and bring messages of interfaith harmony to their constituencies and revisit what is the true message of Pakistan.”

In addition, entities like Karachi’s The Second Floor, Lahore’s Books n Beans, as well as The Last Word, provide venues for local people to have a voice and add to activities that promote harmony and cohesiveness. “State actors could learn important lessons from these non-state actors’ playbooks,” Weiss pointed out. “It’s not about wiping out opposition, but rather transforming how people think about their own society.”

“What I explore in the book are the laudatory efforts of Pakistanis who want their culture back, their lives back and wish to live collectively in a future without violence,” she continued. “These are new, innovative acts being used to either recapture local identity or to contribute to creating a new syncretic one…and saying ‘stop’ to the violent extremism that has manifest over the past decade or even longer in Pakistan.”

In her writing, Weiss celebrates cultural performances, music and social activism, “which are all flourishing in Pakistan today because of people’s commitment to take stands against extremism,” she noted. “What is occurring today is a concerted effort by Pakistanis themselves to bring people together at the public level to reject extremism, to recapture their cultural values and identity and to celebrate their society.”

For centuries, Pakistanis have celebrated their culture through poetry. And in today’s world, a new generation of Pashto poets has grown up directly opposing violence, Weiss said.

“When Geo TV reports on bombings in Peshawar, in the background crowds are often heard singing Pashto anti-war and resistance poetry that speaks out against hypocrisy, unrestrained power and oppression,” she said. “Their Sindhi counterparts hold on strongly to traditions of interfaith harmony laid out in the poetry of Sachal Sarmast and Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai and celebrated today in the poetry of Hafiz Nizamani, Khalil Kumbar, Saif Samejo and Ishaq Samejo.”

Weiss describes Pashto and Sindhi poetry as “resistance poetry,” pointing to the words of the late Abdul Rahim Roghani. “His poetry speaks to how terrorism and political corruption have embroiled Pashtuns in a conflict not of their making, ultimately transforming their society,” she related.

“Writing poetry that enables people to process the violence occurring around them and empowering these same people to stand up to oppression to that violence is formidable,” she continued. “So, too, is reminding people through art that local culture has value and peace is possible. These kinds of actions affect people’s mindsets enabling them to make choices to stand up for their society and against violent extremism.”

Turning to the role the United States could play in viably countering extremism in Pakistan, Weiss suggested the US should “listen to people within Pakistan…and look at what Pakistanis themselves are doing. It is not just about providing money, it’s about narratives,” she argued. “There really are exciting positive things happening within Pakistan today.”

Weiss lauded the activities and methods of the Open Society Foundation in Pakistan, which asks local civil society groups what they need to help build a society open to all. After hearing proposals, the organization has given them funding for many projects.

In Countering Violent Extremism in Pakistan, Weiss explores a representative sample of what local people are engaged in, seeing “sparks of hope that local people are creating to counter violent extremism,” and observing not only what people are doing, but also how they are creating alternative narratives about culture and identity.

In the years Weiss travelled throughout Pakistan – on back roads and places she never imagined visiting – she found “local people responding quite powerfully,” she marveled, “standing up to violent extremism through music, art, writing or whatever means inspires them.”

(Elaine Pasquini is a freelance journalist. Her reports appear in the Washington Report on Middle East Affairs and Nuze.Ink.)