In “Refugee” Author Azmat Ashraf Documents the Other Genocide of 1971 in Bangladesh

By Ras H. Siddiqui

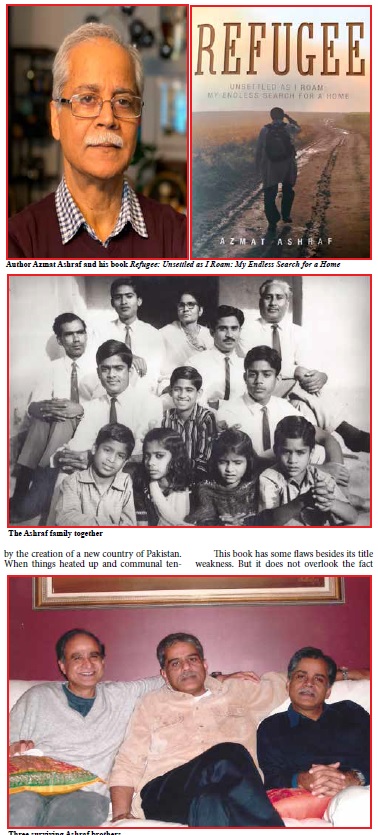

During this time of the COVID-19 pandemic when the world is at war with a virus, a book with the long title of “Refugee: Unsettled as I Roam: My Endless Search for a Home” by first-time writer Azmat Ashraf could easily be overlooked. But that should not happen.

Published in August last year, this is a long overdue work of non-fiction, a voice from the forgotten pages of history which tells the truth from and about the losing side. Yes, George Harrison of The Beatles did organize a “Concert for Bangladesh” in 1971 and the country did win a very bloody and painful independence from Pakistan during that year. Hundreds of thousands of people were killed in what was then East Pakistan where the Bengali majority rebelled against West Pakistani dominance. Author Azmat Ashraf resides in Canada, possibly his sixth and hopefully last migration since birth, hence the title of the book.

There have been several books written from the winning side on the birth of Bangladesh and the happenings in (then) East Pakistan during the year 1971. The narrative for the war that year stands completely overwhelmed by the Indian and Bangladeshi version of events. The losing West Pakistani and especially the Urdu-speaking “Bihari” perspective has not even had a seat at the table to tell their story. Aquila Ismail’s “Of Martyrs and Marigolds” a fictional work does come to mind but by and large the “Biharis” have kept unusually quiet along with the Pakistanis. But their voices cannot remain silent forever.

The sole culprits of the 1971 genocide in Bangladesh have been identified as the Pakistan Army in hundreds of books on this topic. But the truth which was known, and is now slowly emerging, is that the reality was far more complicated. That truth is revealed in this work. Azmat Ashraf could have easily made the title of his work “Refugee: Bangladesh and the Other Genocide of 1971” for better identification and target marketing purposes. But we can chalk that one for a possible future change. In the meantime, let the power of the truth from the losing side get some world attention too.

The journey from East Pakistan to Bangladesh in 1971 was probably not what the author’s father Hayat Ashraf and his Uncle Ansari had in mind when they moved to the newly created country of Pakistan from their ancestral home in India after the partition of 1947. Nor did they anticipate getting shot or hacked to death because they spoke a different language, but that is what happened. The Ashrafs were a family of 10 (the two parents and eight children) settled in the small town of Thakurgaon (north west corner of East Pakistan not too far from the Indian border). By the time Bangladesh was celebrating the joys of its victory only three of them were left alive.

Mass atrocities did take place in former East Pakistan during 1971 but the perpetrators were not solely the Pakistan Army. It was a year of madness during which all the inhabitants, the secessionists and the upholders of the status quo, collectively burnt down their own house (with some fuel provided by the neighboring country). The book is eye-opening and really painful to read even today 50 years later.

Slowly and meticulously Azmat tells the story of his family, the Ashrafs who worked hard in their newly adopted land and did their level best to assimilate into the Bengali majority of then East Pakistan. Azmat’s own journey began with his birth in India. “To slap a final stamp of anonymity, no birth certificate is issued since I was delivered by a midwife at my grandma’s house in the village of Kumhrauli in Bihar, India.” The village Pundit was called to predict his future. “This boy is very lucky. He will travel the world,” the pundit declares gleefully, seeing a hint of a mole on my right foot.” It appears that the pundit was only half right. This boy would travel the world at great expense.

The family in India stood divided on migrating to Pakistan after 1947. It contained members who followed Maulana Azad who stood against partition and those inspired by the creation of a new country of Pakistan. When things heated up and communal tensions and violence rose in Bihar and West Bengal during that period, some members of the family, including Azmat’s father, decided to take the plunge and moved to East Pakistan. Out of the frying pan into the fire almost 20 years later. First becoming targets due to their religion and ending up as targets due to the language (Urdu) they spoke at home.

This book has some flaws besides its title weakness. But it does not overlook the fact that the Bengali-Bihari relationship in former East Pakistan was once quite harmonious. This scribe is eyewitness to that fact and looks back every March for answers to why this madness began and who drew the first blood? The majority of Ashrafs family was killed on April 10 th and 13 th in 1971. All were defenseless human beings including his 10-year-old sister. His views on the politicians of the time and their demise may be openly harsh but how can one blame him for expressing his opinion?

Ashraf recalls: “The Bihari community estimated that between 150,000 and 200,000 perished across East Pakistan…” He goes on to add, “Had the Bengalis not been so brutal in their struggle for independence towards defenseless Biharis, it is possible that the Pakistan Army’s response might have been more measured. Many Pakistani soldiers and their families were killed during the initial uprising.” And as a final quote from the book in this review: “Ironically, it was the brutalities against the Urdu-speaking Biharis that put Bangladesh on the fast track to freedom. The organizers and perpetrators of the massacre fled across the border to India. The Pakistan army ended up subjecting innocent Bengalis to all kinds of excesses in their wild goose chase, causing a bigger exodus.”

The word “exodus” is associated with refugees everywhere. It also reminds one of the Jewish holocaust carried out by the Nazis under Hitler. In my conversation with Azmat Ashraf we did discuss that not all the world’s refugees, including South Asians, can come and settle in America and Canada. But the words “Never again” did come up. Azmat said that education might be the key to prevention and wants readers to know of a unique program in the United States which he hopes that our young people might show some interest in (details below).

The MA program in Holocaust and Genocide Studies at Stockton University (New Jersey, USA)

MA Fellowships on Refugees and Displaced Persons are available. Applicants need to apply online here: https://stockton.edu/graduate/holocaust-genocide-studies.html (go to Admissions Criteria). Students interested in this opportunity should contact Dr Raz Segal, Associate Professor Holocaust and Genocide Studies program at Stockton, before beginning their online application at Raz.Segal@Stockton.edu .

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Back to Pakistanlink Homepage