“Rural America is much more diverse than we recognize. Punjabis have contributed a huge amount to our agricultural development and economic development and cultural diversity” - NewsNation

Along the Highways, Indian Restaurants Serve America’s Truckers

By Meena Venkataramanan

Vega, Tex: Long before dawn on a frosty February morning in Dallas, Palwinder Singh rises from the mattress in his sleeper cab and prepares to haul his cargo cross-country. After five hours of driving north along US 287, and then west on Interstate 40, it’s lunchtime.

Singh, 30, pulls his semi off Exit 36 into Vega, a quiet town in the Texas Panhandle along the historic Route 66. For lunch, he bypasses the typical long-haul trucker menu of convenience-store snacks and heat-lamp hot dogs at the large Pilot Travel Center and instead rolls into the parking lot of a modest white building across the street. A sign on the building’s red roof spells out the words “Punjabi Dhaba” in the Punjabi language’s Gurmukhi script, with the English translation below it.

The Vega Truck Stop and Indian Kitchen , as it’s officially known, attracts truckers like Singh originally from Punjab, a region spanning northwest India and eastern Pakistan. The store is filled with Punjabi snacks, sweets, truck decorations and a restaurant, known as a dhaba, that serves fresh meals including paratha and butter chicken — a slice of South Asia in the middle of rural Texas.

That afternoon, Singh parked his truck, decorated with colorful fabrics and ornaments called jhalars and parandas. He was promptly greeted in Punjabi by another trucker, Amandeep Singh, of Fresno, California, who had also stopped for lunch. As they each poured a cup of steaming chai indoors, the truckers chatted about their drives.

The Vega eatery is among an estimated 40 dhabas, and likely many more, that have popped up along American highways across the country in response to the growing number of Punjabi truckers, who have dominated the Indian trucking industry for decades. Punjabis now make up almost 20 percent of the US trucking industry, according to Raman Dhillon, chief executive of the North American Punjabi Trucking Association. Punjabis are both truckers and owner-operators, running companies such as Tut Brothers out of Indiana and Khalsa Transportation out of California. They’re challenging the stereotype of the rugged White, male trucker that has long been associated with the industry.

The dhaba’s kitchen appliances whirle and hiss throughout the day, sending ripples of steam into the air as a handful of cooks rotate between julienning vegetables and sauteing them with meat and paneer in large cast-iron karahis -N ashville Scene

“The driving and the trucking is in our blood,” said Dhillon, adding that Punjabi truckers have been riding American highways since the late 1960s, especially in California. “And since then, they just really swelled. For last 10 years, the Punjabi trucking industry is growing very fast and very big.”

The majority of dhaba customers are part of a vast network of Punjabi truckers who share the secrets of the road through WhatsApp groups and TikToks.

“There are many friends, it’s very big, there are 1,021 people in this group,” said Palwinder Singh. He said he found out about the Vega dhaba through the group and pinned it on his personal Google Maps, dotted with various dhabas around the country.

“Sat Sri Akal,” the owner, Beant Sandhu, greets the truckers in Punjabi, extending his arm to shake their hands energetically and making small talk in their native language.

The dhaba’s kitchen appliances whirled and hissed throughout the day, sending ripples of steam into the air as a handful of cooks rotated between julienning vegetables and sauteing them with meat and paneer in large cast-iron karahis.

Sapna Devi, a cook who immigrated from Haryana — an Indian state bordering Punjab — kneaded dough into circles for mixed vegetable paratha. Harry Singh, another line cook and an immigrant, stirred yellow onions in a massive pot before scrambling paneer with it to make bhurji.

Dhabas like the Vega eatery are tucked into truck stops and travel centers at the edges of sleepy American towns, some with almost all-White populations. Punjabi has seeped onto highway signs and billboards; just east of Vega is a truck and trailer sales billboard ad printed almost entirely in the language, alongside a photo of wrestling legends Hulk Hogan and Randy Savage.

It’s a testament to how Punjabi drivers are changing the face of the US trucking industry, the highways they traverse on a daily basis, and in turn, small-town America. And it reflects the growing influence of Punjabis — who are classified as Asians , the fastest-growing racial group in the United States — on rural America.

“Punjabis have done a great deal to uplift a lot of rural America. All up and down Highway 5 through California, you have dhabas, you have gurdwaras [Sikh temples],” said Nicole Ranganath, an assistant professor of Middle East and South Asia studies at the University of California at Davis. “Rural America is much more diverse than we recognize. Punjabis have contributed a huge amount to our agricultural development and economic development and cultural diversity.”

Punjabi immigrants began coming to North America in the early-20th century to work on farms and lumber mills, said Ranganath, who is also the curator of the Pioneering Punjabis Digital Archive.

More recently, she said, Punjabi immigrants have been fleeing rising discrimination and violence against India’s religious minorities, including adherents of Sikhism, the majority religion in the Indian state of Punjab. Many brought farming and trucking skills with them when they emigrated from the region, primarily to California’s Central Valley to do agricultural work.

Vega is home to fewer than 1,000 residents, the vast majority of them White. The town’s claim to fame is its location along the historic Route 66, which accounts for most of its seasonal tourism.

The town’s only South Asian residents are the truck stop’s Punjabi owners and employees and the motel owners across the highway, who are originally from Gujarat in western India. Originally from Moga, a city in central Punjab, the dhaba’s owner, Beant Sandhu, wears a dastaar (turban) and grows out his beard in line with the Sikh tenet of kesh.

“God told me to come here,” said Sandhu, leaning against a counter next to a heat-lamp display of samosas, bread pakoras and aloo patties.

About 55 miles west of the Vega Truck Stop is another highway dhaba in San Jon, NM. And about the same distance to Vega’s east is an I-40 dhaba in the town of Panhandle, Tex, just east of Amarillo — the area’s largest city. Across the state line in Oklahoma, there are more I-40 dhabas near the towns of Sayre and Cromwell. The dhabas also pepper other pockets of small-town America, including in York, Ala , Burns, Wyo , and Overton, Neb , which aren’t known for sizable Punjabi populations.

The Sandhus have made a name for themselves in Vega and say the town has embraced them, despite some residents having reservations about the family when they first moved there.

Sandhu and his wife emigrated from Punjab to Northern California in the 1990s, where they joined a large Punjabi community and had three daughters. Beant Sandhu worked in various physically taxing jobs, including janitorial work. A family friend told them about how lucrative a gas station could be and connected them with an opportunity in Texas. They bought a Chevron gas station in Granbury near Dallas in 2006. Although they found the business rewarding, they wanted “something challenging, something different, something bigger,” said Arjot Sandhu, the Sandhus’ 25-year-old daughter.

“If we want to get out of this, we have to take the risk,” the family thought, according to Arjot, who said her parents uprooted their lives in California to move the family to Texas. “All we had was a pickup truck and our stuff, and then we came straight to Texas.”

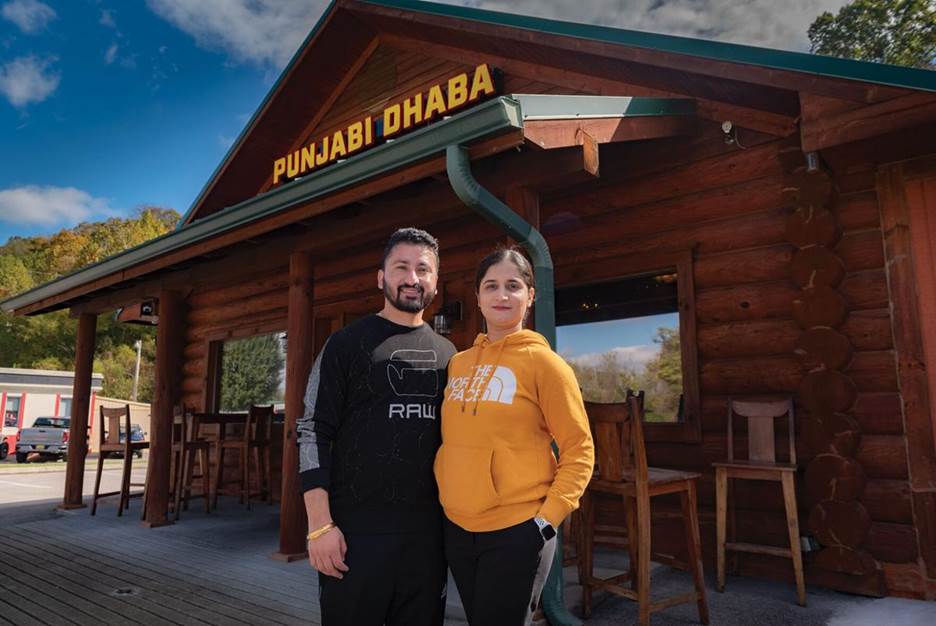

Co-owners Vamsi Yaramaka, left, and Raj Alturu, right, stand inside Eat Spice on Oct 24, 2019, in the truck stop on route 534 off I-80 in White Haven, Pennsylvania. The restaurant caters to members of the Sikh community and as there is a large population of truckers from that community, the Indian Dhaba and Mediterranean dishes become hard to find on the road

In 2018, the Sandhus started a truck stop in Vega. At first they stocked the convenience store with typical American snack fare: potato chips, soft drinks and candy. But they soon discovered that the trucking demographic is “actually more Indian,” said Arjot, than the family had initially thought, and a friend told them about the concept of dhabas along major US highways. As they began to see more Indian customers come in, they started asking them what they’d like to see in the store.

The family began importing groceries from India. “[The dhaba] started growing from word to word, mouth-to-mouth,” said Arjot, who helps her family out at the dhaba, sometimes driving five hours from the Dallas-Fort Worth area on weekends after finishing her classes for the week.

The Vega dhaba is now combed into neat rows of Indian snacks, sweets and spices: Punjabi biscuits flecked with carom seeds, packets of whole cardamom and cloves, and bright blue bags of India’s Magic Masala-flavored, crinkle-cut Lay’s potato chips abound. The convenience store also sells truck ornaments with images of Guru Nanak, Sikhism’s founder, among other items.

In February, the Vega Truck Stop seldom saw a dull moment, with truckers trickling through in a steady stream beginning in late morning into the nighttime. The drivers rolled out of their trucks in comfortable clothing. Jovneek Smith, one of few women in the industry, wore a tracksuit with slippers, and Mohamed Muhudin wore shorts and a T-shirt. Muhudin is part of a growing population of Somali truckers who also patronize the dhaba because Punjabi food has similarities to Somali food, they say.

When the coronavirus pandemic erupted in 2020, the Sandhus, who had previously commuted between the Dallas area and Vega, moved to Vega full time to run the dhaba. Arjot’s younger sisters enrolled in the local schools while she took online classes during her last semester of college. The family adjusted the dhaba’s hours, reducing employees’ schedules and limiting the menu to popular items. Still, they feared their reduced staff couldn’t keep up with demand and that the dhaba wouldn’t make it.

“There were days where we cried so much because there’s orders of like 50 or 60 roti and we have zero made,” Arjot said. “There were days where we’d get so burned out.”

Despite the challenges of the pandemic, business has improved, and the family is hopeful about the dhaba’s future, although they are mindful that their business relies heavily on the conditions of seasonal highway traffic and the trucking industry.

“Whatever they go through, we go through,” Arjot said. “Right now, Punjabi truckers are suffering as they’re not getting the rates they desire or actually need.” Indeed, members of the North American trucking industry have recently threatened strikes over tense contract negotiations.

The family plans to renovate their dhaba this summer, adding showers and gas pumps. These improvements, Arjot said, will help develop the dhaba into a full-service travel center for not only truckers, but also for interstate travelers and local residents.

The Sandhus hope that their renovated dhaba will serve as a model for others, slowly and collectively becoming a staple of the American highway. For her part, Arjot can already envision Punjabi dhabas joining the ranks of big-box truck stops and travel centers peppering motorways.

“It’s just like how you’d go to a Pilot,” she said, “but it’ll be the Punjabi dhaba.” – The Washington Post