Thomas Jefferson’s Qur’an: How Islam Shaped the Founders

By R.B. Bernstein

One of the nastiest aspects of modern culture wars is the controversy raging over the place of Islam and Muslims in Western society. Too many Americans say things about Islam and Muslims that would horrify and offend them if they heard such things said about Christianity or Judaism, Christians or Jews. Unfortunately, those people won’t open Denise A. Spellberg’s Thomas Jefferson’s Qur’an: Islam and the Founders . This enlightening book might cause them to rethink what they’re saying.

Photo Illustration by The Daily Beast

Thomas Jefferson’s Qur’an examines the intersection during the nation’s founding era of two contentious themes in the culture wars—the relationship of Islam to America, and the proper relationship between church and state. The story that it tells ought to be familiar to most Americans, and is familiar to historians of the nation’s founding. And yet, by using Islam as her book’s touchstone, Spellberg brings illuminating freshness to an oft-told tale.

Spellberg, associate professor of history and Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Texas at Austin, seeks to understand the role of Islam in the American struggle to protect religious liberty. She asks how Muslims and their religion fit into eighteenth-century Americans’ models of religious freedom. While conceding that many Americans in that era viewed Islam with suspicion, classifying Muslims as dangerous and unworthy of inclusion within the American experiment, she also shows that such leading figures as Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and George Washington spurned exclusionary arguments, arguing that America should be open to Muslim citizens, office-holders, and even presidents. Spellberg’s point is that, contrary to those today who would dismiss Islam and Muslims as essentially and irretrievably alien to the American experiment and its religious mix, key figures in the era of the nation’s founding argued that that American church-state calculus both could and should make room for Islam and for believing Muslims.

As Spellberg argues with compelling force, the conventional understanding of defining religion’s role in the nation’s public life has at its core a sharp divide between acceptable beliefs (members of most Protestant Christian denominations) and the unacceptable “other.” Many Protestant Americans, for example, disdained the Roman Catholic Church because of their memories of the bitter religious wars of the Protestant Reformation. Further, Pennsylvania’s constitution and laws allowed voting, sitting on juries, and holding office only to those who professed a belief in the divine inspiration of the Old and New Testaments.

By contrast, Thomas Jefferson, a central figure in Spellberg’s book, had a strong, lifelong commitment to religious liberty. Jefferson rejected toleration, the alternative perspective and one embraced by John Locke and John Adams, as grounded on the idea that a religious majority has a right to impose its will on a religious minority, but chooses to be tolerant for reasons of benevolence. Religious liberty, Jefferson argued, denies the majority any right to coerce a dissenting minority, even one hostile to religion. Jefferson rejected using government power to coerce religious belief and practice because it would create a nation of tyrants and hypocrites, as it is impossible to force someone to believe against the promptings of his conscience. Jefferson embraced religious liberty and separation of church and state to protect the individual human mind and the secular political realm from the corrupting alliance of church and state. His political ally James Madison, echoing Roger Williams, the seventeenth-century Baptist religious leader and founder of Rhode Island, added that separation of church and state also would protect the garden of the church from a corrupting alliance with the wilderness of the secular world.

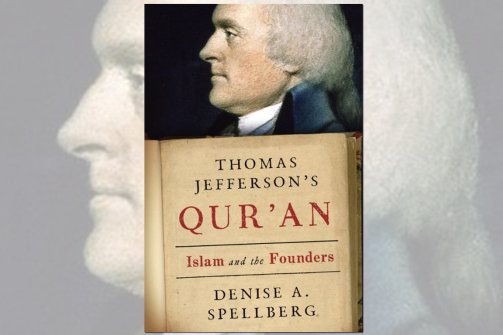

Thomas Jefferson’s Qur’an: Islam and the Founders. By Denise A. Spellberg 416 pages. Knopf. $27.95.

Ranged against separation was a view of church-state relations teaching that government could accommodate religion and need not be neutral between the cause of religion in general and that of irreligion or atheism. Adherents of this view included Samuel Adams, Roger Sherman, and Patrick Henry. The ongoing struggle between these two points of view has shaped and continues to shape American religious history and the law of church and state under the US Constitution.

Spellberg adds to this familiar story well a valuable and unfamiliar twist, introducing Islam as a focal-point of American thought and argument. Were Muslims to be excluded from America? Was Islam antithetical to American ideas of religious freedom and openness of citizenship?

Spellberg begins her answers to these questions by analyzing Europeans’ and Americans’ negative and positive images of Islam between the mid-sixteenth century and the eighteenth century. For example, the French jurist and philosophe Charles Louis Secondat, baron de Montesquieu, made Muslim diplomats the viewpoint characters of his pathbreaking satirical novel The Persian Letters, which presented European laws, institutions, manners, and morals from an “outsider” Muslim perspective. Yet many Europeans and Americans, seeing Muslims as perennial adversaries of Christianity from the Crusades, insisted that Muslims had no claim to religious liberty because of their supposed hostility to the idea of liberty . Turning from a general overview to focus on Jefferson, Spellberg devotes the core of her book to examining his seemingly antithetical views with regard to Islam and its believers. Though Jefferson was a harsh critic of Islam as a religion (as he was of all Abrahamic religions) and of the hostage-taking and ransom-seeking practices of Muslim states in the Mediterranean (the “Barbary Pirates,” against whom he unsuccessfully tried to organize a Euro-American naval alliance), he also was a staunch advocate of religious freedom even for those falling outside the conventional spectrum of Protestant Christian believers, including Catholics, Jews, and Muslims. Jefferson’s views differed from those of his friend and diplomatic colleague John Adams, who dismissed Jefferson’s quest for an alliance against the Barbary states as unrealistic and who rejected the inclusion of Muslims within an evolving American definition of religious freedom.

Probably more Americans distrusted Islam and Muslims than made room for them in the American experiment.

Jefferson and Adams were far from the only Americans who differed about Islam and the status of believing Muslims in America. As Spellberg points out, during the ratification controversy of 1787-1788, the proposed US Constitution’s ban on religious tests for holding federal office (Article VI, clause 1) became a lightning-rod of criticism, with opponents of the Constitution charging that that ban would enable “a Jew, Turk, or infidel” to become president. Nor did these political controversies rage only among those conventionally identified as leading “founding fathers.” A key leader of the Baptist denomination, John Leland, not only backed Jefferson’s and Madison’s campaign against religious establishments in Virginia and on the national stage, but also sided with them on the question of Muslims becoming part of the American experiment. Recognizing that the Baptists faced discrimination and denunciation from more established sects of Protestant Christianity, and taking that experience to heart, Leland opposed discrimination against those who were not part of that favored range of Protestant sects and denominations – including Muslims.

The story at the core of Spellberg’s book privileges her chosen focus on liberty and inclusion while downplaying her account of religious suspicion and bigotry during the American founding. Probably more Americans distrusted Islam and Muslims than made room for them in the American experiment. This paradox poses the sharp question whether we should give weight to a probable numerical majority or to an enlightened minority in assessing constitutional interpretation during the nation’s founding. Spellberg might have framed her book just as plausibly as a tale of conflicting political, constitutional, and religious visions – with the battle between them as pointed and bitter then as it is now.

Nonetheless, one of the most valuable aspects of Thomas Jefferson’s Qur’an is its compelling, formidably documented case that Americans divided on this question in the founding period, as they do today, and that the case for inclusion is far stronger, in substance and in the authority of those embracing it, than the case for exclusion. Stressing the need to remember the enlightened approach to who gets the benefit of the American experiment’s protections of religious liberty, Spellberg’s book is essential reading in these troubled times. – Courtesy The Daily Beast

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Back to Pakistanlink Homepage