Crime but No Punishment in Indian Elections

By Milan Vaishnav

Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

Washington, DC

Elections certainly bring out the best in India’s raucous democracy, but they also expose some of its blemishes. Consider this extraordinary figure: 30 percent of members of parliament have criminal cases pending against them. And that is an increase from the previous election in 2004, when “only” 24 percent of MPs were similarly situated.

In the fight to curb these figures, there have been some positive developments and valiant efforts to raise awareness. The Supreme Court of India recently decided that sitting politicians who are convicted of criminal acts should be removed from office upon conviction—a new practice in India. And for the first time, an anticorruption party vaulted to victory in Delhi’s state assembly. These are certainly bright spots, but, if recent state elections are any indication, efforts thus far have barely scratched the surface.

Real change will take significantly more sweeping measures to get to heart of the crime-politics nexus. In India’s electoral marketplace, as in any market, there are underlying supply and demand factors that facilitate exchange. And in this case, politicians with criminal records are supplying what voters and parties demand: candidates who are effective and well-funded.

The Nature of the Phenomenon

A wellspring of information about India’s political class was tapped in 2003, introducing a new level of transparency about India’s electoral aspirants and elected officials. In response to landmark public interest litigation filed by civil society watchdogs, the Supreme Court of India ruled that any person standing for elected office at the state or national level must submit, at the time of nomination, a judicial affidavit detailing his or her financial assets and liabilities, education qualifications, and pending criminal cases.

The disclosures are not without their shortcomings. Crucially, the information is self-reported, which means that in the case of financial details in particular, the accuracy of the affidavits can be questioned. In addition, the data on criminality refers to ongoing cases rather than convictions; due to the vagaries of India’s justice system, it can take decades for an indictment to produce a conviction, if at all.

Nevertheless, the data—taken as a whole—gives a reasonable snapshot of the biographical profiles of India’s most influential lawmakers. And the picture isn’t pretty.

The 15th Lok Sabha (lower house of parliament), whose term expires at the end of May 2014, is home to 162 MPs with pending criminal cases. These cases involve a diverse array of charges, both large and small, ranging from mischief to murder and nearly everything in between. If one were to focus only on serious charges —those unrelated to electioneering or a politician’s daily vocation such as those involving murder, kidnapping, and physical assault—approximately 14 percent or 76 MPs face pending cases.

The situation at the state and local levels, though lacking comparable scrutiny, is similar. Roughly one in three members of state assemblies (31 percent) is involved in at least one criminal case. Again about half, roughly 15 percent, face serious charges.

There has been no systematic analysis of panchayats (village governments) and urban local bodies, but there is evidence that local tiers of governance are hardly free of criminality. Based on data collected by the Association for Democratic Reforms , 17 percent and 21 percent of municipal corporators in Mumbai and Delhi, respectively, declared involvement in criminal cases.

Why Parties Supply Criminal Politicians

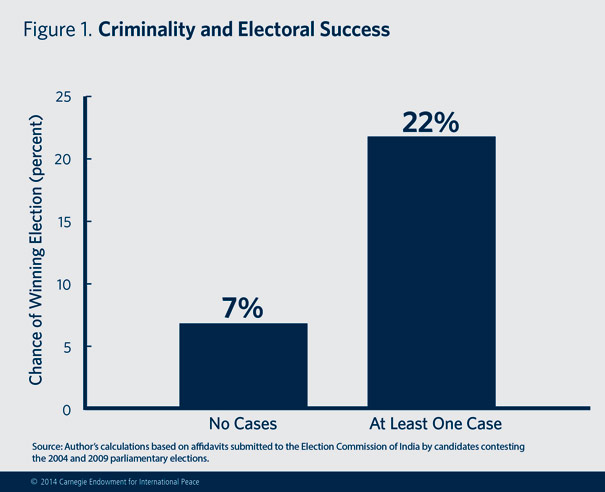

In one sense, the answer to why political parties in India nominate candidates with criminal backgrounds is painfully obvious: because they win. In the 2004 or the 2009 parliamentary elections, a candidate with no criminal cases pending had—on average—a 7 percent chance of winning. Compare this with a candidate facing a criminal charge: he or she had a 22 percent chance of winning. Granted, this simple comparison does not take into account numerous other factors such as education, party, or type of electoral constituency. Nevertheless, the contrast is marked.

Of course, the real question is what makes these candidates winnable. At least part of the answer comes down to cold, hard cash—an area in which those who break the law often have a leg up. Election costs in India have grown considerably over the years thanks to a host of factors, including a growing population, a marked increase in the competiveness of elections, and elevated voter expectations of pre-election handouts.

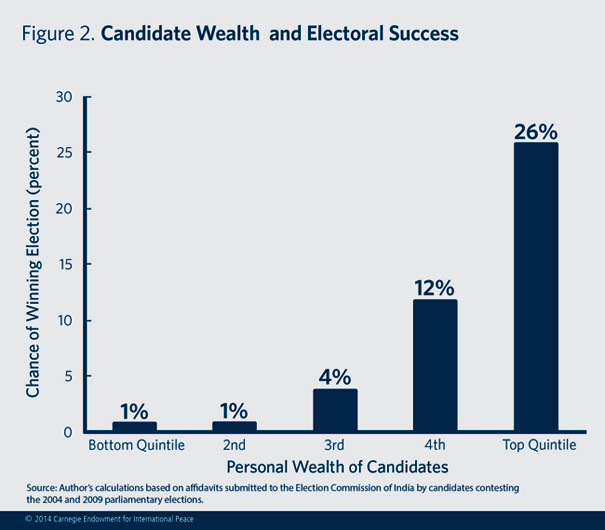

Money does not buy elections in India; what a well-financed campaign buys is viability. Indeed, there is a strong correlation between a parliamentary candidate’s personal assets—a good proxy for financial capacity—and the likelihood of election. Drawing on data from 2004 and 2009, the poorest 20 percent of candidates, in terms of personal financial assets, had a 1 percent chance of winning parliamentary elections. The richest quintile, in contrast, had a greater than 25 percent shot.

Beyond the draw of a higher likelihood of success, parties value “muscle” (criminality, in Indian parlance) because it often brings with it the added benefit of money.

As election costs have soared, parties have struggled to find legitimate sources of funding, which is a partial reflection of the general decline in their organizational strength. As a result, they place a premium on candidates who can bring resources into the party and will not drain limited party coffers. The quest for private funds is further propelled by an ineffectual election finance regime, which is marked by numerous loopholes and a lack of transparency.

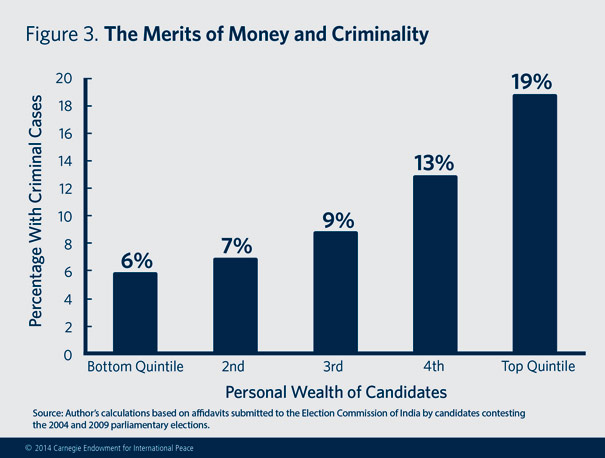

When it comes to campaign cash, candidates accused of breaking the law have a distinct advantage: they both have access to liquid forms of finance and are willing to deploy it in the service of politics. In the last two parliamentary elections, roughly 6 percent of candidates in the lowest quintile of candidate wealth (or poorest one-fifth) faced criminal cases compared to nearly 20 percent of candidates in the top quintile.

Voter Demand for Criminal Politicians

Money is an important part of the story but, on its own, is an insufficient explanation—if only because parties have access to wealthy candidates who are not linked to criminal activity, from cricket heroes to film stars and industrialists. It is also not immediately clear why voters would prefer a wealthy, “tainted” candidate to an equally wealthy, “clean” alternative.

As the deputy president of the state unit of one major party confided to me back in 2010, candidates with criminal records thrive because they have “currency.” It turns out that this “currency” is also figurative.

While many have suggested that voters in India unwittingly support tainted politicians because they are ignorant about the biographies of their political representatives, there is an affirmative explanation that is consistent with rational, well-informed voters. In contexts where the rule of law is weak and social divisions are highly salient, politicians often use their criminal reputation as a badge of honor—a signal of their credibility to protect the interests of their parochial community and its allies, from physical safety to access to government benefits and social insurance. The “protection” on offer is often grounded in the language of caste or religious empowerment and can be readily justified in defensive terms. One member of Maharashtra’s Shiv Sena party with a reputation as a strongman explained his “hands-on” approach to the scholar Thomas Blom Hansen: “If someone enters my house and runs away with my roti [bread] then what should I do? I have to slap him and take the roti away because it is my roti and not his.”

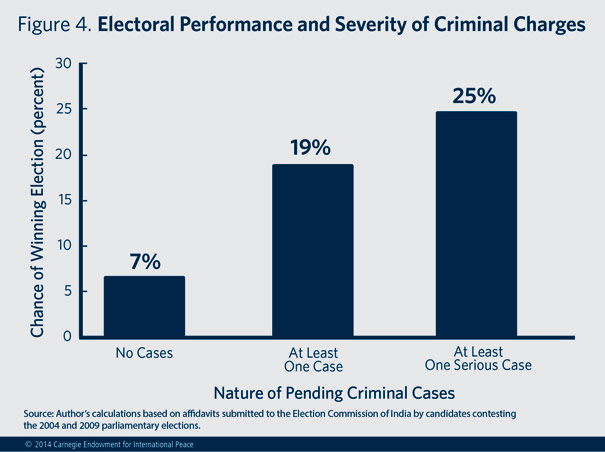

The appeal of candidates who are willing to do what it takes—by hook or crook—to protect the interests of their community provides some intuition for why the odds of a parliamentary candidate winning an election actually increase with the severity of the charges, with slightly diminishing returns in the most severe instances.

The Rhythm of Elections

Elections in India have acquired a sort of customary rhythm over the years. Part and parcel of this rhythm is the spate of news headlines before elections about the sordid biographical details of aspirants to higher office. Once voting is completed and the results are announced, a second wave of stories about the criminal antecedents of those who are actually elected pours forth. Recent judicial action is a positive step, but interrupting this rhythm requires deeper institutional change.

The unexpected victory in Delhi of the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP), which campaigned on an avowedly anticorruption platform, is also a positive sign of popular frustration with malfeasance, but it is unlikely to be a game changer. The AAP proved a party could win without heavily resorting to candidates with lengthy rap sheets, but that did not seem deter the party’s rivals. According to the Association for Democratic Reforms , 21 percent of the ruling Congress Party’s candidates and 46 percent of the opposition Bharatiya Janata Party’s candidates were involved in criminal cases, compared to 7 percent for the AAP.

If the high levels of criminality in politics could be attributed to a lack of information about candidates’ biographies, a public awareness campaign might make a significant dent in criminality rates. Alas, the situation is far more nuanced.

India needs a credible election finance regime with real teeth to rein in under-the-table funding. And the state’s ability to impartially deliver benefits, physical safety, and timely justice has to improve. Unless an investment in institutional change is made, parties—as well as many voters—will continue to view a candidate’s criminal reputation as a potential asset rather than a liability. ( Danielle Smogard provided excellent research assistance for this article. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace)

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Back to Pakistanlink Homepage