Sahir: The Poet Magician of Ludhiana

By Dr Mohammad Taqi

Florida

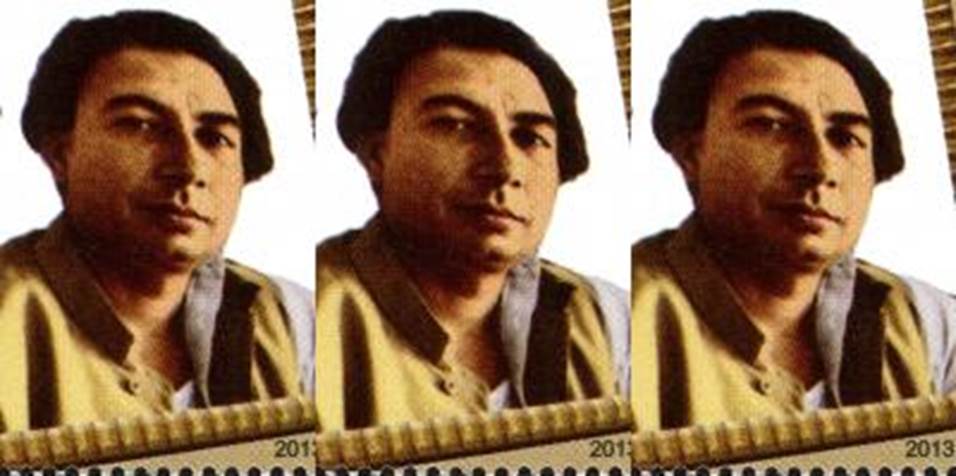

TheWire/ India Post, GoI/Wikimedia Commons CC BY 3.0

The birthday of Sahir Ludhianvi, one of the foremost Urdu progressive poets of the 20th century, went largely unnoticed last weekend. Up until a few years ago when that indefatigable chronicler of the subcontinent’s progressive movement, Hamid Akhtar, was still alive, one would see a piece or two from him remembering his compadre Sahir.

While the songs he wrote for films pop up on the social radar frequently, Sahir’s life and literary contributions seem to be slowly slipping away from memory. I recall that as late as the 1980s, Sahir’s first collection, Talkhiyan (rancor) was essential reading in leftist study groups. Anyone initiated in Marxist circles would almost certainly come across Sahir’s famous lines written at the execution of the Congolese independence leader and socialist icon, Patrice Lumumba:

“Zulm phir zulm hai, barrhta hai to mitjata hai

Khoon phir khoon hai, tapkay ga to jam jaiyga”

(Repression is but repression, it can grow but it will not last

Blood is still blood, it spills, but repression it shall outlast).

Undivided Punjab’s greater Ludhiana area has given Urdu the three greats: Sher Muhammad Khan, Akhtar Ali and Abdul Hai, who became known by their pennames Ibne Insha, Hameed Akhtar and Sahir Ludhianvi, respectively. Abdul Hai was born on March 8, 1921, in the city of Ludhiana to a feudal, Chaudhry Fazal Mohammed, and one of his several wives, Sardar Begum. Sahir’s parents had an acrimonious divorce in which he sided with his mother and testified in the court against his quite brutal father.

His mother raised him in abject poverty. Sahir went to the Malva Khalsa School and then the Government College at Ludhiana where he gravitated towards student politics and joined the All-India Students Federation, which was allied with the Communist Party of India (CPI). Sahir became the president of the student union at the Government College and a progressive poet almost simultaneously. By most accounts he was eased out of the college for his defiance against visiting British dignitaries but the precipitating event perhaps was his fling with a girl on which the college officials frowned. Subsequently, he moved to Lahore circa 1943 along with his mother, where he was also joined by his comrade, Hameed Akhtar. He continued with the cycle of his student political activism and ensuing expulsion at Dayal Singh College, and then the Islamia College, Lahore.

It was, however, in the same fateful year that his first poetry collection, Talkhiyan, was published by the progressive outlet Preet-Larri. The short collection, most of it written during his college days, catapulted Sahir into the top tier of Indian Urdu writers at the age of 22. The leftist Progressive Writers Association (PWA) welcomed him as one of their equals and as a poet after which there was no looking back for Sahir. He distinguished himself from other revolutionary poets like Faiz Ahmed Faiz and Josh Malihabadi under whose influence he had initially labored, and Allama Iqbal, from whose poem he had apparently adopted his takhallus (nom de plume), Sahir (the magician).

On the eve of 1947, Sahir was in Bombay participating in PWA and CPI activities as well as making a rather lackadaisical entry into song writing for what is now called Bollywood. As India was divided he, worried sick about his mother, dashed back via Ludhiana to Lahore. He joined the editorial staff of the leftist literary journal Savera (dawn), which quickly earned him the ire of Pakistani officials who ordered his arrest. Without telling even his buddy Hameed Akhtar and the Communist Party of Pakistan’s (CPP’s) secretary general, Sajjad Zahir, Sahir took off for New Delhi in 1949 and, after a brief sojourn there, ended up in Bombay. Hameed Akhtar said that Sahir’s concern was not just an arrest but also his rather prophetic assessment that Pakistan would end up being ruled by the “mullah and jagirdar” (clergy and the feudal).

Sahir had to toil without much luck for a good two years before the celebrated musician Sachin Dev ‘SD’ Burman gave him a break. Sahir wrote the song Thandi Hawaain, Lehra Kay Aain extempore to Burman’s tune and virtually never looked back after that. Sahir’s pairing with SD Burman under the cinematic prodigy Guru Dutt produced one after another super hit scores. He wrote hundreds of songs for dozens of Bollywood movies without once compromising on poetic quality. He set not only the literary but also the intellectual and philosophical benchmark so high that hardly any of his peers could match it.

Rebellion remains the leitmotif of Sahir’s film and non-film poetry, which moves from the elation of romance and revolution to resentment and resignation and, at times, despair. Nowhere is this panoply of thought and emotion expressed better than the 1958 film Pyaasa, which Guru Dutt directed and also performed the lead role in after Dilip Kumar turned it down.

Pyaasa, ranked fifth among Time magazine’s top romantic movies of all time, is unmistakably an imprint of Sahir’s life and work. Sahir updated his massively popular poem Chaklay (brothels) from Talkhiyan for Pyaasa by changing the refrain from “Sanakhwan-e-taqdees-e-mashriqkahanhein” (where are those who sing paeans to the East’s sanctity) to “jinheinnaaz hai Hind pewohkahanhein” (where are those who boast about India) to inflict a massively bitter reality check in post-independence India. The film culminates with Guru Dutt’s signature performance that brings to life not just Sahir’s words but also his deep-seated resentment against oppression and a certain resignation to his fate with the crescendo:

“Jala do isay, phoonk dalo yeh dunya

Meray samnay se hata lo yeh dunya

tumhari hai, tum hi sanbhalo yeh dunya

yehdunya agar mil bhijaiy to kiya hai?”

(Torch this world, to ashes blow this world

Remove it, I do not wish to see this world

This is your world; I will let you handle this world

For even if I get it, what worth is this world?).

From the Lenin Peace Prize to Filmfare Awards to the Padma Shri, all have acknowledged Sahir’s socio-political struggle and his poetic genius but he summed up his colossal contribution as:

“Ruja’t-pasand hoon kehta rraqi-pasand hoon

Iss beh sko fuzool o abus janta hoo nmein ...

Taaron k ianjuman se mujhay naheen

Insaniyat pe ashk bahata raha hoon mein

dunya ne tajar baat o hawa diskishakl mein

jo kuchh mujhey diya hay, woh lauta raha hoon mein”

(Am I a reactionary or am I a progressive?

This debate to me is so retrogressive

I have nothing to do with the assembly of stars

Tears I shed are for mankind’s scars

What the world gave me as trial and experiment

I have returned thus with a compliment).

(This article first appeared in 2015)