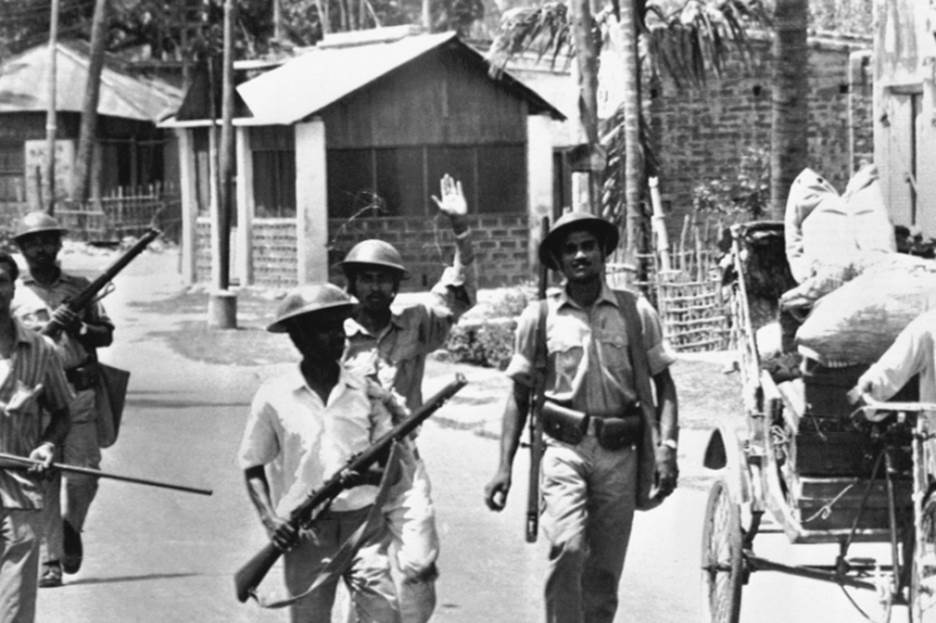

Uniformed East Pakistan rebel forces with armed civilians patrol a street in Jessore, April 2, 1971 - AP

1971 – Part 1

By Dr Khalid Siddiqui

Ohio

The sequence of events starting in March 1971 and culminating in the separation of East Pakistan as a new country of Bangladesh remains largely a haphazard bunch of events for the people who lived in West Pakistan (WP) during that time. The most important reason was the deliberate misinformation spread by the government-controlled news media.

Over the years the residents of WP (later Pakistan) expunged the 1971 tragedy from their memories as if it never happened. It reached such a high level of denial that a friend of mine, while narrating the creation of Pakistan to a PBS program, stated that in 1947 the Indian subcontinent was split into India and WP. The map of WP was shown as the ONLY Pakistan of 1947. When I questioned him about it, he had no satisfactory answer to give.

Our children also know very little of those events. The tragedy that befell on the non-Bengalis especially the Biharis has been buried under the rug. One million Urdu-speaking Muslims migrated to East Pakistan (EP), mostly from Bihar, India, and also from UP, CP, Hyderabad (Deccan), Rajasthan and Gujarat, over two decades since 1947. They constituted 2% of the total population of EP. More than 50% of these ‘Biharis’ were killed in 1971/72.

Another 500,000 non-Urdu speaking Muslims migrated to EP from West Bengal, Assam, Orissa, Burma and South India. I have tried in this article to summarize these events in a simple chronological order. I have read many books on this subject written by Pakistani and Indian writers, which are mostly biased.

The first book on this topic ‘Witness to Surrender’ was written by Siddiq Salik. Coming from an Army man, it deals mostly with battlefield tactics. The two books by the Western authors that appear credible are: ‘Dead Reckoning’ by Sirmila Bose from the UK, and ‘Blood Telegram’ by Gary Bass from the USA. Two English books, ‘A Legacy of Blood’ by Anthony Mascarenhas and ‘The Lightning Campaign’ by Maj Gen D. K. Palit, are totally biased and far from reality. Another English book ‘Blood and Tears’ by Qutubuddin Aziz consists of interviews of 170 eyewitnesses from among the 5,000 Biharis repatriated to Pakistan. They were chosen from the worst-affected 55 towns and cities of EP. A personal account in Urdu جیون ایک کہانی by Ali Ahmad Khan is okay. However, the best eye-witness account is given in the book ‘Refugee’ by Azmat Ashraf. ‘The East Pakistan Tragedy’ by L. Rushbrook Williams is incomplete because it doesn’t go beyond August, 1971. Yasmin Siakia, Prof. of History at Arizona State University, in her book ‘Women, War, and the Making of Bangladesh’ writes about the unpopular subject of sexual violence against the women in the 1971 war. Ikram Sehgal in his book ‘Blood over Different Shades of Green’ discusses mostly international politics and Pakistani military strategy – with many inaccuracies. The most recent book is ‘Creation of Bangladesh’ by Junaid Ahmad. It is a potpourri of what has been written by others before him.

Very little has been written about the sufferings, throughout this period, of the civilian non-combatants, mostly the ‘Biharis’. I personally interviewed many friends as well as strangers who were witnesses and victims of these atrocities in Dacca, Chittagong, Sylhet, Rajshahi, Lalmonirhat, Santahar, Dinajpur, Thakurgaon and Khulna. Names of many locations would sound unfamiliar to most people, but those who have lived in East Pakistan should be able to relate to them. The timeline has been divided into five parts.

GLOSSARY:

Bihari: People who migrated to Pakistan from the State of Bihar in India

‘Bihari’: All non-Bengali-speaking persons including the Biharis

2IC: Second in Command

AL: Awami League

Battalion/Regiment: 750-900 troops with a Lt. Col as CO

BSF: Indian Border Security Force

CMC: Chittagong Medical College

CO: Commanding Officer

EBR: East Bengal Regiment – consisted of Bengali troops with 10-20% WP officers

EBRC: East Bengal Regimental Center

EP: East Pakistan or East Pakistani

EPCAF: East Pakistan Civil Armed Forces

EPR: East Pakistan Rifles – like Rangers in Pakistan. 20% of the EPR personnel were from WP

GOC: General Officer Commanding

ICRC: International Committee of the Red Cross

JPMC: Jinnah Postgraduate Medical Centre

Mukti Bahini: Awami League militants fighting for Independent Bangladesh

Nationalists: The civilian Bengalis who supported the creation of Bangladesh

PA: Pakistan Army

PER: Pakistan Eastern Railways

PPP: Pakistan Peoples Party

UNHCR: United Nations High Commission for Refugees

WP: West Pakistan or West Pakistani

PART 1: December 7, 1970 to March 24, 1971

On December 7, 1970, general elections were held in Pakistan. Out of the total of 313 seats contested in the National Assembly, the Awami League (AL) led by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman won 167, and PPP led by Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto won 86 seats. All of the 167 seats won by AL were from EP; and all of the 86 seats won by PPP were from WP. The rest of the two seats in EP and 58 seats in WP were won by other political parties and the Independents.

With the sole exception of Bhutto, the leaders of all the other political parties from West Pakistan were willing to accept a government led by the Awami League. President Yahya Khan arranged talks between Bhutto and Mujib to arrive at a consensus in order to frame the future constitution. Mujib asserted his majority and stressed his intentions of framing a constitution based on his six points. Bhutto's argument was that there were two majorities – one in each wing. Mujib rejected Bhutto's demands for a share in power. The talks failed. Bhutto announced his decision to boycott the National Assembly session which was to be held in Dacca on March 3, 1971. He warned the other West Pakistani politicians of physical violence if they decided to attend the Assembly session. Bhutto requested Yahya to delay the National Assembly session. When Yahya announced the delay on March 1, 1971, Bengali masses staged protest marches throughout EP.

The non-Bengalis of EP could be divided loosely into three categories. Almost all of the ones who had migrated from Bihar, West Bengal, Orissa and Madras had the intention of settling down in EP permanently. So, they tried to integrate into the Bengali culture. The migrants from UP, CP, Hyderabad, Gujarat and Bombay were there for work or business, and were planning to move to WP eventually. So, they didn’t find it necessary to have their roots in EP. Besides there were West Pakistanis on a temporary basis in EP: students; businessmen; government workers on deputation; Pathan security guards, etc. Their roots were in WP. They learned about the Bengali culture, especially the language, just enough to get by.

The ‘Biharis’ were considered the sympathizers of Pakistan. Starting March 1, 1971, there were incidents of killing of ‘Biharis’ by Bengali mobs in the towns and cities of EP. Around 150 ‘Biharis’ were killed in Chittagong. As my school was surrounded by the Bihari colonies, some Bihari families from the outlying areas moved into the school for security. The police, which was almost all Bengali, didn’t intervene to protect the ‘Biharis’. Isolated incidents continued. There were some Bengali casualties also. Neither party used guns at that point. 23 Army personnel were also killed throughout EP in random incidents. The Pakistani government deliberately suppressed the news of this communal riot to avoid a backlash against the small population of Bengalis living in Karachi.

Rumors were circulating that many injured Bengalis had been admitted to the Chittagong Medical College (CMC). As a result, a large mob had gathered outside the hospital. The main big iron gate was closed by the hospital administration, and guards were posted who would allow only the patients and their relatives through the gate. There was no such unrest within the hospital where I was a senior surgical resident. Most patients were discharged from the ER after urgent care for minor injuries. Any discharged patient was scrutinized by the mob gathered outside the gate to check whether he was a Bengali or ‘Bihari’? One patient who was found to be ‘Bihari’ was beaten to death by the mob. I and Dr Anwar Ul Haque, another resident, watched all that ourselves with horror from the third-floor balcony of the hospital – fifty yards away. That’s when I decided to leave EP as soon as possible.

One Bihari businessman sustained a fracture of the humerus which needed fixation under general anesthesia. Of course, it was too dangerous to go to the hospital. The Clinical Assistant (my immediate boss) was a Bihari who knew this businessman well. We had a very good relationship with our Professor, Dr Karim, who was a Bengali. We mustered enough courage to seek his help. He agreed and suggested that we bring the patient to his house, and he would arrange for a reliable anesthesiologist, who was also a Bengali. The procedure was performed at the professor’s house without any problem. So, there were some neutral Bengalis also. The businessman, of course, had to dole out a large chunk of cash. I met Dr Karim for the last time in 1987 in Dhaka. He passed away a few years back.

This mayhem lasted only for a day or two and the situation, apparently, calmed down to normal after that. The EPR had been deployed in the cities which was reassuring. In Chittagong it had established its headquarters at the Niaz Stadium, very close to my house. Peace Committees consisting of Bengalis and Biharis were formed in various neighborhoods to maintain law and order. It, however, later turned out to be a ploy by the Bengalis to get information on the location of the Bihari houses, and the number of inhabitants in each one of them.

Apparently, a calm persisted but the Bengali youths would march on the streets with bamboo sticks, knives and party flags shouting ‘Joy Bangla’. Except for a few sporadic incidents there was no violence. However, this was enough to unnerve the non-Bengali residents of EP. The people who had West Pakistani connections, but were in EP for employment or studies, started leaving EP. There was a mad rush at the airports to catch an outgoing flight. The settled Biharis, who could afford, also started leaving EP for WP. Many Biharis who had built private homes in East Pakistan were, obviously, very reluctant to leave. There was widespread anticipation that Mujibur Rahman would announce Independence on March 23. Already, the national anthem of Bangladesh was being played at radio stations. All the Urdu programs from West Pakistan had been blocked. The Bangladeshi flag, which was different from the one adopted later, was on display everywhere.

On March 7 there was a public gathering at Ramna Race Course ground addressed by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. Although he avoided direct reference to independence, as talks were still underway, he warned his listeners to prepare for an imminent confrontation.

Yahya Khan went to Dhaka in the middle of March in a last ditch attempt to obtain a resolution. Bhutto joined him. However, the three parties could not come to a consensus on the transfer of power. Yahya was willing to accept the Six Points, demand for autonomy, and also Mujib as the prime minister. However, for Bhutto, this was tantamount to treason.

Secretly, during this time, the Bengali youths were joining Mukti Bahini in preparation for an impending clash with the Pakistan Army (PA). The leaders higher up had determined that, in order to tackle the PA, the ‘Biharis’ had to be eliminated. They knew that the ‘Biharis’ couldn’t be trusted, and they would provide logistical support to the PA. The Bengali members of the peace committees announced on megaphones for the Biharis to deposit their arms to a central location, which the Biharis did. The arms looted from different locations like Rifle Clubs were distributed to the Mukti Bahini cadres, and to the students at the universities. In a jail-break at the Central Prison in Dacca on March 6, some 341 prisoners escaped and joined hands with Mukti Bahini and the student activists in parading the main streets of Dacca.

Pakistan Army also started taking steps in preparation for an Army Action. They began relocating the Bengali officers away from sensitive areas, and bringing in Pakistani troops to the cities. The departure of two Pakistan Army units, the 25 Punjab and the 20 Baluch, was delayed, while the 13 Frontier Force and the 22 Baluch regiments were flown to Dacca from West Pakistan before March 25. Two infantry divisions were ready in Karachi to be sent as reinforcements. To maintain secrecy, no major reinforcements were sent to the other garrisons in EP from Dacca until March 25. Bengali units were sent out of the cantonments, or were broken into smaller units and deployed away from each other, and cut off from the main radio and wireless communication grid before or on March 25. Bengali officers were sent on leave or were posted away from command centers or units directly involved in the operation.

In some cases, WP officers took command of Bengali formations. Some Bengali soldiers were sent on leave, and some were disarmed on various pretexts wherever possible without raising alarm. WP soldiers in EPR were posted in the cities where possible while Bengali soldiers in EPR were sent to the border outposts. Many WP Army officers had started sending their families back home. Others moved them to the cities, away from the cantonment. At the same time the civilian ‘Biharis’ started moving into the cantonment areas for security.

Retired Bengali Army Officer, Col Osmani, was de facto military advisor to the Awami League. Bengali military officers, despite all the precautions, were alarmed by the buildup of Pakistani forces. Concerned about their own safety, they started contacting Awami League leaders through Osmani. He coordinated the activities of the Bengali units. The Awami League leadership, attempting a political solution, did not endorse any action, or preparation for conflict by the Bengali soldiers preemptively. Warnings by Bengali officers that the Pakistan Army was preparing to strike were ignored, and junior Bengali officers were told by their superiors to be prudent and avoid political issues.

A large number of ‘Biharis’ were employed by the PER. They lived in the Railway colonies along with the Bengali employees. By a rough estimate the ‘Biharis’ constituted between 50 and 75 % of the total population of these colonies. In addition, there were exclusive ‘Mohajir’ colonies in the big cities like Dacca and Chittagong, and also in some other smaller towns where they were in substantial numbers. These colonies were built on the land given by the government to the immigrants. Only Biharis lived in it. The well-known ones were Mohammadpur and Mirpur in Dacca.

My family consisting of my parents and three brothers (another brother was in the USA) boarded the ship, Rustom, to leave Chittagong port on March 22. There were more than double the number of usual passengers on board. A large number of Pathans and their families were going back. Voluntarily, all the older folks and the families were accommodated in the sheltered areas, whereas young men and boys spent their days and nights on the open deck. Fortunately, it didn’t rain during those seven days. The food was rationed but it was sufficient. The ship was to make a stopover in Colombo to pick up supplies but, because of some disturbances there, the crew decided to skip it and head straight for Karachi.

On March 23, 1971, while on the ship, we heard Mujib informing Yahya Khan that he must issue the orders for regional autonomy within 2 days, otherwise he wouldn’t be able to control the violent and restless masses. While the talks were still underway, Yahya had already decided on the military solution. A final meeting was held at the GHQ. The Governor of EP, Vice-Admiral Ahsan and Air Officer Commanding of PAF base in Dacca, Air Commodore Zafar Masud objected to the army operation. So, both were relieved of their posts.

Attempts to unload arms and ammunition from MV Swat (docked in Chittagong port) between March 20 and 25 were a partial failure. Brig Mozumdar (a Bengali), had refused to open fire on Bengali civilians who were blocking the unloading. He was the senior-most Bengali Army officer in EP, and a security risk. He was lured to Dacca by Maj. Gen. Khadim Hussain Raja, relieved of his post, and arrested. Brig. Ansari took over his position in Chittagong and unloaded the ship.

(To be continued)

-