Ukraine's Lesson for Pakistan: Never Give up Nuclear Weapons

By Riaz Haq

CA

Commenting on Ukraine, Russian analyst Alexey Kupriyanov told Indian journalist Nirupama Subramanian: "For us, Ukraine is the same as Pakistan for India". What he failed to mention is that Pakistan has developed and retains its nuclear arsenal while Ukraine gave up its nukes in the 1990s after the fall of the Soviet Union.

Many Ukrainians now regret that decision. Ukrainians know that no country with nuclear weapons has ever been physically invaded by a foreign military. They now understand the proven effectiveness of nuclear deterrence. They realize that all the talk about "rules-based order" is simply empty rhetoric. The reality is the Law of the Jungle where the strong prey on the weak.

|

Ukraine gave up nukes in the 1990s. Source: Utica Phoenix |

Denuclearization of Ukraine

When Ukraine became independent in the early 1990s, it was the third-largest nuclear power in the world with thousands of nuclear arms. In the years that followed, Ukraine made the decision to denuclearize completely based on security guarantee from the US, the UK, and Russia, known as the Budapest Memorandum. Ukrainian analyst Mariana Budjeryn explained in an interview with NPR's Mary Louise Kelly as follows:

"It is clear that Ukrainians knew they weren't getting the exactly - sort of these legally binding, really robust security guarantees they sought. But they were told at the time that the United States and Western powers - so certainly, at least, the United States and Great Britain, they take their political commitments really seriously. This is a document signed at the highest level by the heads of state".

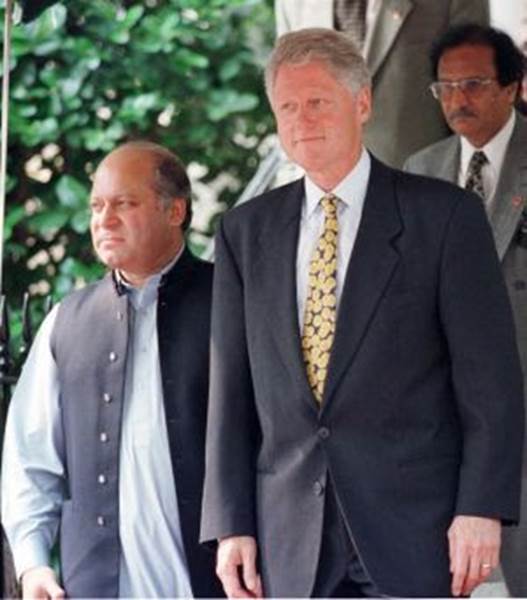

US Efforts to Stop Pakistan's Nukes

The order to conduct Pakistan's nuclear tests came from Mr Nawaz Sharif who was Pakistan's prime minister in 1998. It came on May 28, just over two weeks after India's nuclear tests were conducted on May 11 to May 13, 1998. Pakistan went ahead with the tests in spite of the US pressure to abstain from testing. US President Bill Clinton called Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif immediately after the Indian tests to urge restraint. It was followed up by Deputy Secretary of State Strobe Talbott's visit to Islamabad on May 16, 1998.

In his 2010 book titled " Engaging India: Diplomacy, Democracy, and the Bomb ", Secretary Talbott has described US diplomatic efforts to dissuade Pakistan in the two weeks period between the Indian and Pakistani nuclear tests . Here are a few excerpts of the book divided into four sections covering Clinton's call to Sharif, Talbott's visits to the Foreign Office (FO), General Headquarters (GHQ) and Prime Minister's House:

Clinton's Call to Sharif

Clinton telephoned Sharif, the Pakistani PM, to whet his appetite for the planes, huge amounts of financial aid, and a prize certain to appeal to Sharif—an invitation for him to make an official visit to Washington.

“You can almost hear the guy wringing his hands and sweating,” Clinton said after hanging up.

Still, we had to keep trying. Our best chance was an emergency dose of face-to-face diplomacy. It was decided that I would fly to Pakistan and make the case to Nawaz Sharif.

Meeting at Foreign Office in Islamabad

On arrival in Islamabad, we had about an hour to freshen up at a hotel before our first official meeting, which was with the foreign minister, Gohar Ayub Khan, and the foreign secretary (the senior civil servant in the ministry), Shamshad Ahmad.

When we got to the foreign ministry, we found that the Pakistani civilian leaders had finally figured out how to handle our visit, and the result was a bracing experience. My two hosts rolled their eyes, mumbled imprecations under their breath, and constantly interrupted.

They accused the United States of having turned a blind eye to the BJP’s preparations for the test.

As for the carrots I had brought, the Pakistanis gave me a version of the reaction I had gotten from General Wahid five years earlier. Offers of Pressler relief and delivery of “those rotting and virtually obsolete air- planes,” said Gohar Ayub, were “shoddy rugs you’ve tried to sell us before.” The Pakistani people, he added, “would mock us if we accepted your offer. They will take to the streets in protest.”

I replied that Pakistanis were more likely to protest if they didn’t have jobs. Gohar Ayub and Shamshad Ahmad waved the point aside. The two Pakistani officials were dismissive. The current burst of international outrage against India would dissipate rapidly, they predicted.

Visit to General Headquarters (GHQ) in Rawalpindi

We set off with police escort, sirens blaring, to (Chief of Army Staff) General Karamat’s headquarters in Rawalpindi.

Karamat, who was soft-spoken and self-confident, did not waste time on polemics. He heard us out and acknowledged the validity of at least some of our arguments, especially those concerning the danger that, by testing, Pakistan would land itself, as he put it, “in the doghouse alongside India.”

His government was still “wrestling” with the question of what to do he said, which sounded like a euphemism for civilian dithering. There was more in the way Karamat talked about his political leadership, a subtle but discernible undertone of long-suffering patience bordering on scorn. For example, he noted pointedly “speculation” that Pakistan was looking for some sort of American security guarantee, presumably a promise that the US would come to Pakistan’s defense if it was attacked by India, in exchange for not testing. “You may hear such a suggestion later,” Karamat added, perhaps referring to our upcoming meeting with Nawaz Sharif. I should not take such hints seriously, he said, since they reflected the panic of the politicians. Pakistan would look out for its own defense.

What Pakistan needed from the United States was a new, more solid relationship in which there was no “arm- twisting” or “forcing us into corners.” By stressing this point, Karamat made clear that our arguments against testing did not impress him.

Meeting at Prime Minister's House

I shared a car back to Islamabad with Bruce Riedel and Tom Simons to meet Nawaz Sharif.

What we got from the Prime Minister was a Hamlet act, convincing in its own way—that is, I think he was genuinely feeling torn—but rather pathetic.

On this occasion Nawaz Sharif seemed nearly paralyzed with exhaustion, anguish, and fear. He was—literally, just as Clinton had sensed during their phone call—wringing his hands. He had yet to make up his mind, he kept telling us. Left to his own judgment, he would not test.

His position was “awkward.” His government didn’t want to engage in “tit-for-tat exchanges” or “act irresponsibly.” The Indian leaders who had set off the explosion were “madmen” and he didn’t want “madly to follow suit.”

But pressure was “mounting by the hour” from all sides, including from the opposition led by his predecessor and would-be successor, Benazir Bhutto. “I am an elected official, and I cannot ignore popular sentiment.” Sharif was worried that India would not only get away with what it had done but profit from it as well. When international anger receded, the sanctions would melt away, and the BJP would parlay India’s new status as a declared nuclear weapons state into a permanent seat on UN SC. I laid out all that we could do for Pakistan, although this time I tried to personalize the list a bit more.

Clinton told me two days before that he would use Sharif’s visit to Washington and Clinton’s own to Pakistan to “dramatize” the world’s gratitude if Sharif refrains from testing. This point aroused the first flicker of interest I’d seen. Nawaz Sharif asked if Clinton would promise to skip India on his trip and come only to Pakistan. There was no way I could promise that. All I could tell Nawaz Sharif was that Clinton would “recalibrate the length and character” of the stops he made in New Delhi and Islamabad to reflect that Pakistan was in favor with the United States while India was not. Sharif looked more miserable than ever.

Toward the end of the meeting, Sharif asked everyone but me to wait outside. (Foreign Secretary) Shamshad (Ahmad) seemed miffed. He glanced nervously over his shoulder as he left. When we were alone, I gave the prime minister a written note from Secretary Albright urging him to hold firm against those clamoring to test. The note warned about the economic damage, to say nothing of the military danger, Pakistan faced from an escalating competition with India. Sharif read the note intently, folded the paper, put his head in his hands for a moment, then looked at me with desperation in his eyes.

At issue, he said, was his own survival. “How can I take your advice if I’m out of office?” If he did as we wanted, the next time I came to Islamabad, I'd find myself dealing not with a clean-shaven moderate like himself but with an Islamic fundamentalist “who has a long beard.” He concluded by reiterating he had not made up his mind about testing. “If a final decision had been reached I'd be in a much calmer state of mind. Believe me when I tell you that my heart is with you. I appreciate and would even privately agree with what you're advising us to do.”

Summary:After the Russian invasion of Ukraine, many Ukrainians are regretting the decision to give up their nuclear weapons in 1990s based on Western security assurances. In 1998, Pakistan flatly refused to do what the Ukrainians did. It is clear from Secretary Talbot's description that Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif did not want to go forward with the nuclear tests, but he had no choice. Fearing that he would be removed from office if he decided not to conduct atomic test, he told Talbott, “How can I take your advice if I’m out of office?” Summing up the failure of the US efforts to stop Pakistan's nuclear tests, US Ambassador to Pakistan Ann Patterson said the following in a cable to Washington in 2009 : "The Pakistani establishment, as we saw in 1998 with the nuclear test, does not view assistance -- even sizable assistance to their own entities -- as a trade-off for national security vis-a-vis India."

(Riaz Haq is a Silicon Valley-based Pakistani-American analyst and writer. He blogs at www.riazhaq.com )