History Extra

Giants and Myths

Milestones on the Road to Partition – Part 1

By Professor Nazeer Ahmed

CA

The partition of British India was an extraordinary event. It brought forth giant personalities, monumental egos, brilliant strategists, saints, scoundrels, politicians, thinkers, tinkers, stinkers, sages, and sycophants.

Like an angry volcano it spewed forth human passions in their ugliest form consuming oceans of humanity. In its aftermath it left more than a million dead, fifteen million refugees and tens of thousands of women raped. Two nations inherited the Raj and were immediately locked in mortal combat. A third nation has sprung up since, while the first two, India and Pakistan, now nuclear armed, continue to stare at each other waiting to see who will blink first.

The last chapter of the history of partition is yet to be written. The secret of whether it will have a tragic end with a nuclear holocaust or a happy new beginning with cooperation and brotherhood for the poverty-stricken millions of the subcontinent is hidden in the womb of the future, dependent as is all human endeavor, on the wisdom of generations to come.

British India was a vast tapestry woven together by a masterful balance of local powers and sustained by an unabashed strategy of divide and rule. It was a mosaic of religions, languages, races, cultures, tribes, castes, historical memories, passions and prejudices. More than five hundred princely states, satraps of the British crown, dotted the landscape, surrounded by vast stretches of territories ruled directly by the Viceroy. The foreigners had come here in the seventeenth century to trade. As the Mogul empire disintegrated and India imploded, the traders moved like dexterous chessmen capturing one territory after another. From the fall of Bengal at the Battle of Plassey in 1757 to the drawing up of the Durand Line in 1893-95 after the Second Anglo-Afghan war, there was a span of almost a century and a half. During this time British power moved inexorably, supplanting a divided India by force of arms as in Mysore and the Punjab or through treaties and manipulation as with the Nizam of Hyderabad and the Nawab of Arcot.

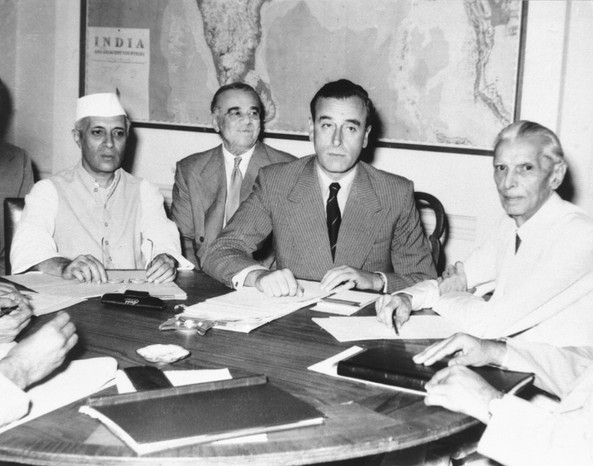

The independence movements of India and Pakistan brought forth giants on the stage of world history. Mahatma Gandhi was at once a sage in the tradition of Indian sages, a staunch advocate of non-violent political change, a masterful tactician and a politician who deciphered the key to unravel the British Empire. His legacy inspired reformers and activists as far away as the United States from which Martin Luther King and the Civil Rights Movement drew inspiration.

Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah was a strict constitutionalist, a parliamentarian, a brilliant strategist, a secular gentleman, a champion of minority rights and a nationalist who was pushed in the direction of separatism by Congress obduracy and became the architect of a new nation thereby changing the map of the world.

Pandit Jawarlal Nehru was an internationalist, an eclectic post-modern secularist, indeed an agnostic, whose instincts for centralized, socialist planning obscured from him the reality of communal politics in a divided subcontinent. Sardar Patel was a fierce nationalist and right-wing Congressman who moved towards a sectarian anti-Muslim bias in the twilight years of the British Raj. Maulana Abdul Kalam Azad was a scholar whom destiny thrust into politics, the only man who fought unswervingly for a united India until the last moment.

All of these stalwarts operated in the nineteenth century paradigm of nationalism, colonial rule, parliamentary governance, and minority and majority rights. Together, they failed to foresee the horrors of partition or to muster the collective wisdom to forestall the carnage that accompanied it. The independence of India and Pakistan was their collective achievement. Partition was their collective failure.

A student of history may ask: who was the architect of partition? Allama Iqbal? Gandhi? Jinnah? Nehru? Patel? The Congress party? The Hindu Mahasabha? The Muslim League? The Akali Dal? The British? We are deliberately making a distinction here between independence and partition. No one person and no single party can take the credit or the blame for partition. It was a deadly serious game that had many players. The principal figures involved have acquired an iconic status in India and Pakistan. Often the hero of one is a villain for the other, so bitter was the experience of partition. Sixty years later, when one looks at them as historical figures, one finds them to be all too human, with their prides and their prejudices, their strengths and their limitations. They made choices like all humans and these choices had the human touch of triumph and tragedy. They were as much creators of history as were its victims.

Britain entered the First World War as the mistress of the world. The British navy ruled the seas. In 1914 an Englishman could boast that the sun never set on the British Empire. The array of nations beholden to the British crown included dominions such as Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa, and colonies such as India, Malaya, and Nigeria.

World War I was a spillover from the instability in the Balkans following the collapse of Ottoman power. It resulted from the unwillingness or the inability of the entente powers, Great Britain, France and Russia to accommodate the rising power of Germany. The Ottomans joined the war alongside Germany in the hope of recovering the East European territories they had lost in the war of 1911. It was a fateful decision which shattered the peace of the Middle East, the consequences of which are felt even today.

India was dragged into the Great War as a colony. Indian leadership, Gokhale, Tilak, Jinnah and Gandhi included, were disappointed that they were not consulted but could do nothing about it. Millions of Indian troops fought under British officers in Europe and the Middle East. In some sectors, such as Iraq, the Indian army conducted its own operations. The Indians hoped that their sacrifices would bring in a reward at the end of the war, perhaps a dominion status within the Empire, on par with Australia, South Africa and Canada.

These hopes received a boost as the United States entered the war in 1917 and its idealist American President, Woodrow Wilson, proclaimed his famous 14 Point plank as the basis for a general peace after the War. Included in these 14 points was the declaration that “a free, open-minded, and absolutely impartial adjustment of all colonial claims, based upon a strict observance of the principle that in determining all such questions of sovereignty the interests of the populations concerned must have equal weight with the equitable claims of the government whose title is to be determined”.

An attempt was made during World War I by the Indian National Congress and the Muslim League to present a unified demand to the imperial government in India for administrative reforms. Mohammed Ali Jinnah, who was at the time a senior member of the Congress hierarchy, worked hard to achieve a common platform for the Congress and the League. The result was the Lucknow Pact of 1916 in which the Congress conceded the right of Muslims for separate electorates. The pact was the high point of Congress-Muslim League cooperation during the long and tortuous history of these two political parties.

The credit for this achievement belongs primarily to Jinnah. The Pact made it possible for the Congress and the League to make a unified demand to the colonial administration that eighty percent of representatives to the provincial legislatures be elected directed by the people. (To be continued)