Fighting Cancer Taught Me about Resilience, Kindness, and Gratitude – I

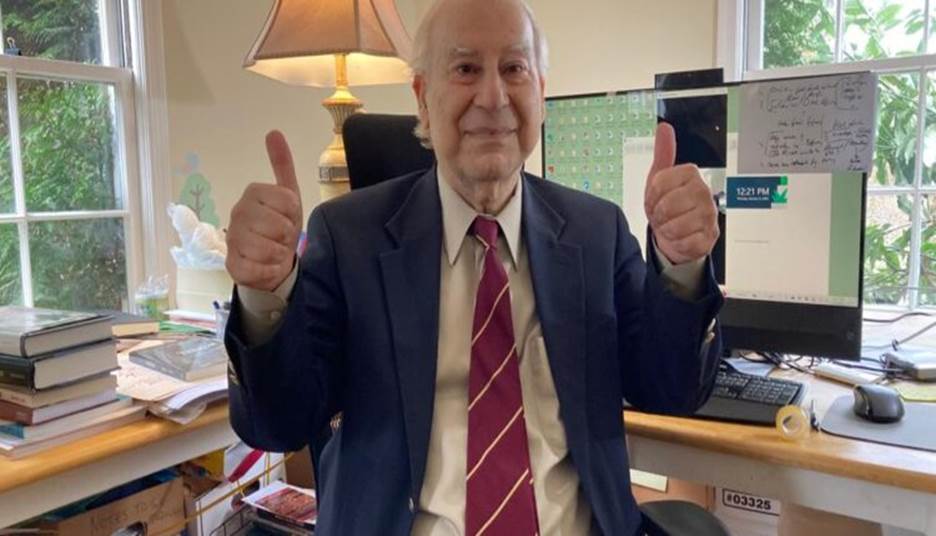

By Dr Akbar Ahmed

American University

Washington, DC

Editors’ Note : We are publishing this two-part series of a deeply personal and moving account of how scholar and former Ambassador Dr Akbar S. Ahmed fought with cancer and reflected on life and its various gifts. This is also a reminder for our readers on the importance of self-care, mindfulness, and regular medical check-ups to overcome the biggest threat to public health.

Owing to its deadly and treacherous nature, cancer is widely dubbed as “the Emperor of all maladies.” Recently, the Emperor came calling to my home.

The Emperor first attacked me and then, immediately after, when I was at my weakest, it attacked Amineh, our eldest child. Amineh was our pride and joy and her birth may well have saved my life as result of which we called her our “miracle baby”. She had grown to be a dignified, serious, compassionate and deeply spiritual scholar. Her case raised the question in all of us, why would God allow something as terrible as cancer to afflict someone as devoted and decent as Amineh?

We had spent the summer of 2018 visiting first the UK, then Pakistan and back to the UK before flying home to Washington, DC. It was a program heavy with lectures and events. Unusually, I had begun to feel tired. Besides, in Pakistan it was hot and there were long journeys on dusty roads. I was invited by Ambassador Masood Khan, the president of Azad Jammu and Kashmir, to lecture at his universities in Muzzafarabad and Mirpur. They were great visits with large audiences asking intelligent questions. We also travelled to Swat and to Lahore, but I was finding these trips exhausting. Something was wrong with me. I was not sure what exactly and like most people I was not very keen to find out.

On my return, I felt lethargic. Then a crisis jolted me. It started with a lot of blood and pain as I passed urine. It had never ever happened before. The pain was excruciating and the fear palpable. Something was terribly wrong. I was rushed to the ER and all the practical issues came up. Who drives? Which hospital? What next? What did this blood mean? Cancer in a foreign land in a time of hostility to Muslims in the time of Donald Trump. Not a happy prospect.

I consulted my doctor who ordered some blood tests. He discovered that my PSA which is the guide to the health of the prostate, and an indication of cancer, was dangerously high and rapidly climbing. It was cancer and of an aggressive variety. If unchecked it would enter my blood stream and I would be in serious trouble. The doctor immediately ordered a series of further tests and biopsies. The next few months were a blur of terrifying procedures and examinations concluding in a visit to Dr Stephen Greco, a well-known oncologist at John Hopkins Hospital.

When I first heard of my predicament in late 2018, my thoughts were confused and alarmed. You ask yourself: why me? Is it to do with my genes or a poor diet, or perhaps lack of exercise? If you think in religious terms you ask, “Is God somehow unhappy with me?”

You slowly come to realize it is a combination of these things, except God’s unhappiness. God is Rahman and Rahim, Beneficent and Compassionate. It is really the cells in the body breaking down. The bad cells will eventually kill the patient unless checked. The problem with the treatment is, with radiation for example, the good cells are also damaged.

Treatment

I first realized the seriousness of the matter when we discussed the early results with an oncologist at Georgetown University Hospital. On hearing his prognosis my wife Zeenat had tears in her eyes. I call her sherni or tiger because of her courage and devotion. But seeing those tears in her eyes shook me. If she was upset, it dawned on me, the matter was obviously serious. She now stepped into the role of guide, nurse, doctor, driver, cook, matron and philosopher. She drove me every morning to and from the hospital. Without her, my treatment would have been impossible. With her I felt I could go through it. She made it sound easy with her strength and her love. Her tips were practical and invaluable: Fight it. Be positive. Exercise. Take one day at a time. Just focus on curing yourself. After a certain age, nature works to kill us off, so be grateful we have time. We are lucky we have access to hospitals and doctors. Every time you are tired lie down. Nose running, fatigue and sometimes feeling miserable is part of it. Don’t keep pushing non-stop. It was like menopause, she explained. It was not fun. She emphasized to me, like a mother telling a child, do not multi-task, take things in your stride. I found her sayings most helpful and especially in that condition when I could not think too clearly for myself. Your mind will be foggy. “Chemo brain,” she warned me. During this entire period she had become my guardian angel.

On first discussing the presence of the disease my doctor gave me the pep talk and said he would adopt a “zero tolerance” policy towards my cancer. That sounded gung-ho and encouraging. He also said it would “change my life.” I wasn’t sure what he meant, but didn’t like what he was implying. Let’s see, I said to myself. I had faced many challenges before.

Zero tolerance meant that my insides were going to be literally cooked. The doctors were not taking chances and they were going to blast the bad cancer cells. The problem was that in the process they would also kill the good cells. And every day became a challenge – the simple act of picking up a glass of water or going to the toilet to urinate became an exercise in courage. At one point you balance the need to survive with the will to live. It isn’t just the sheer physical demands of the malady but the indignity of your role as passive and helpless patient.

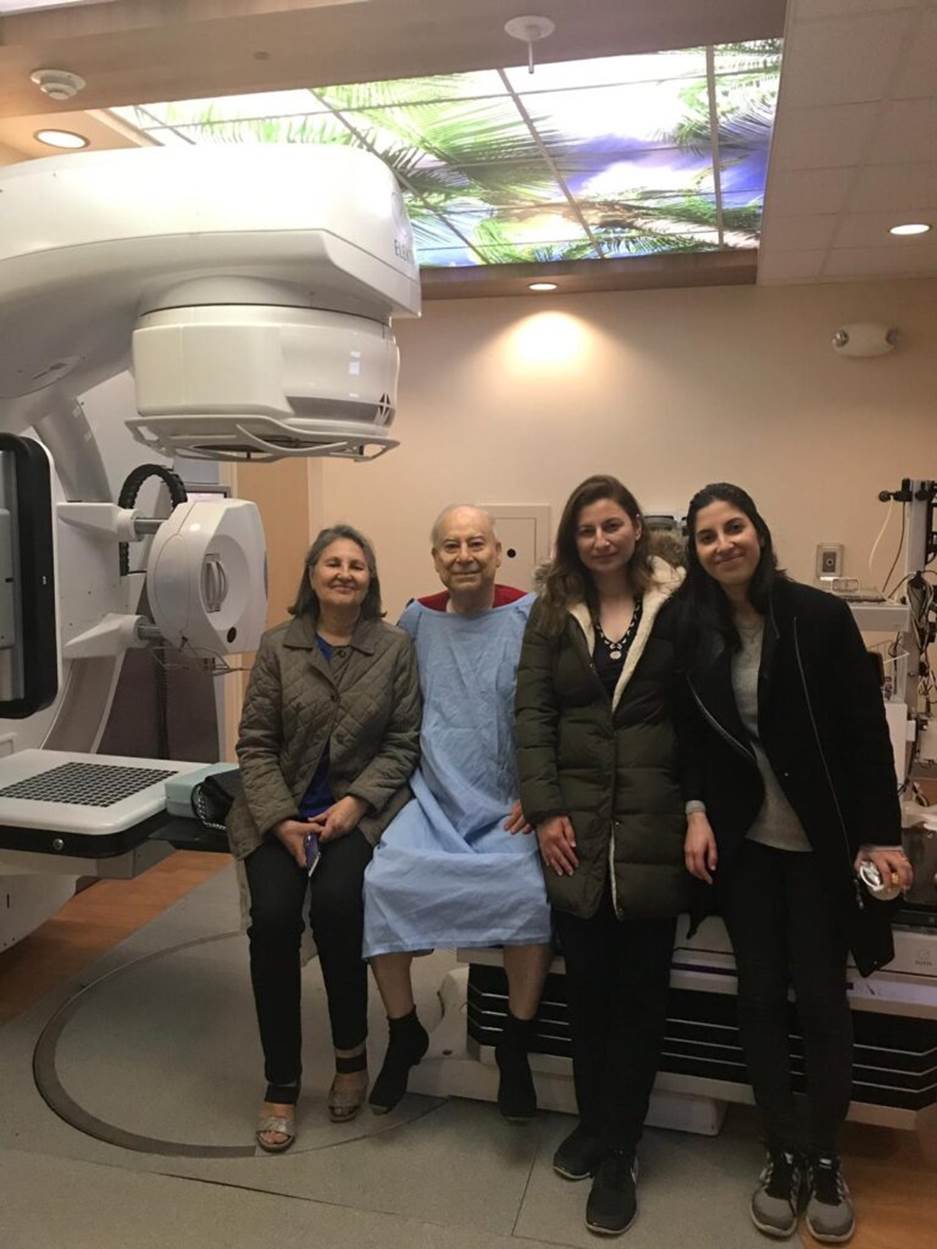

I have avoided doctors and pills – even aspirin – all my life and now suddenly I was going through scans, blood tests, MRI, Catscan, bladder probe and colonoscopy. The Lupron and Casadex were equal to having Chemotherapy. Golden markers were injected in me, and tattoos marked on me in preparation for the treatment that was to follow. The radiation was all-out non-stop and daily. The actual laser took little more than about 10 mins on the table but preparations and leading up to it was a full day and all -night exercise, so effectively it was a 24-hour cycle. And there were no shortcuts.

But as the series of tests and then the radiation began, I realized the significance of Dr Greco’s remarks. I felt tired, hesitant, scared and unsure. As the radiation proceeded, I began to find it difficult to even walk a few paces without feeling exhausted. I felt like an astronaut wearing his space suit and walking with effort in slow motion. My nose ran but I had no cold, and I was warned my bones were fragile and in danger of breaking. My waking, sleeping, urinating and defecating, everything was affected. By week one of the radiation, I felt weak and tired. I moved in slow motion and the spark had gone. Instead, I had hot flashes and mood swings. During the day, especially the mornings, my legs were like lead and my head was in a fog and I understood the expression, death warmed over.

Two months into radiation, I felt like something out of an episode I saw in a nature documentary on television. It was about a gazelle and a lion in which the film maker explains the kill technique of the lion. The lion chases the gazelle until it tires and falls often on its side or back. The lion then sinks its huge teeth into the neck of the gazelle and does not let it go. It also blocks the nose and mouth so the gazelle cannot breathe. All the while the lion’s group, calmly feed on the gazelle which is still alive, tearing chunks of its flesh. That is how cancer attacks a patient.

The radiation experience itself was mind numbing. For two months every morning at a precise time I entered the radiation ward, changed into a thin robe and was escorted into the radiation rooms where no visitors were allowed. I was lain flat on my back and asked to hold a ring tightly and remain absolutely motionless. I stared at a monstrous space age looking machine. It seemed to move on its own volition, peering at me, swinging round me as if it was an alien probe examining a human specimen. I felt I was helpless, paralyzed, inside the belly of a mechanical octopus which was all around and staring intently at me and it moved abruptly from time to time, first in one direction then another, making small grunting sounds, its tentacles inches from my face and body. When the technicians left the room, and I was told to be motionless the radiation would start, and the machine would move round by itself and blast a targeted area in my abdomen marked by a series of tattoos that remain as a permanent reminder. I was told that the radiation was powerful and would continue to “cook” or “fry” my insides for some time afterwards. In order to prevent burning of the skin I was to apply creams.

The preparation for the radiation was almost as bad as the radiation itself. I had to empty my bowels and fill my bladder in order to arrive for the radiation procedure. I had to have milk of magnesia for the former and drink several bottles of water for the latter. If my bladder was below a certain level on arrival, they would cancel the treatment that day. A full bladder was linked to a certain angle of the laser for the radiation. I was constantly terrified that something would go wrong in the arrangement which meant I was up most of the night trying to follow instructions and sipping water.

Those were bad months. On top of everything I continued teaching my classes, never letting on that there was anything wrong with me. There were some days when standing up and facing a classroom of students would terrify me in case I passed out. But the notion of the stiff upper lip was deeply ingrained in me.

I did however develop a philosophy of resistance. I knew I was fighting the biggest battle of my life with the most treacherous enemy. I developed great humility. I relied on the kindness of strangers. I dug deep for reserves of courage. I heard Zeenat tell the children she never heard me complain or groan and moan however hard the treatment. But I knew this was a termination event. The stakes were high. It dawned on me: This could be it. Amineh talked of the “fear factor”. The word cancer is so scary. Every moment became a gift, every minute with Zeenat and the children was like Christmas.

There were really bad days at the height of the treatment when I was being subjected to the full dose of daily radiation and ordered to take all those drugs meant to kill the bad cancer cells but which I was warned will also inadvertently kill the good ones. Every few hours I felt hot flushes round the clock, night and day, burning my face and making me sweat. For weeks I felt miserable though I put on a brave face. On bad days I felt like an incubus was sucking out my inner soul and the drugs and injections were numbing — frying is the right word– my brains. Every movement is a heroic effort and every word uttered a struggle to stagger past the vocal chords. You are not dead but not fully alive.

But through the haze I still saw a silver lining. Even during the worst days of relentless radiation, I noted the common humanity of our world. As I entered the radiation room after stripping and putting on a smock, Zeenat had to wait outside and from then on I was on my own at the mercy of a group of young technicians. Once I heard two young females talking quietly as I lay flat on my back with my eyes closed. They whispered that they enjoyed the smell of my after-shave scent. When I was finished, they asked for the name. Of the two most consistent technicians who attended me one was Michael Cohen and the other Previn Chako. I told Zeenat that once inside the radiation room my fate lay in the hands of a young Jewish and a young Hindu technician. They could not be kinder.

One day, I was chatting with Michael Cohen while lying flat on my back and they were preparing the machine. In the background there was some music playing. Michael asked if I had any favorite songs. I said, do you guys know Dean Martin and Frank Sinatra. Michael said, “old blue eyes,” referring to Sinatra with a smile. When they left me after readying me for my treatment, I heard Dean Martin’s famous songs,” That’s Amore” and “Everybody loves somebody.” As I lay there alone and miserable, I felt comforted by the familiar songs from my youth, but also touched by the gesture of kindness. I could not help the tear that trickled down the side of my face as I lay motionless and prone. The tear was an involuntary warm symbol of joy and gratitude for our common humanity; strangely out of place yet triumphant in this cold and sterile mechanized hospital room. (Continued)