If we examine Pakistan’s greenhouse gas emissions, the country’s contribution amounts to less than one percent of global emissions, yet Pakistan has been ranked as the eighth most vulnerable country to climate crisis - Image courtesy of Ali Hyder Junejo on Flickr

One Year after the 2022 Pakistan Floods

By Gul-i-Hina van der Zwan

It has been almost a year since deadly floods engulfed Pakistan. Last summer during the months of June and October, Pakistan was hit by catastrophic flooding, primarily caused by torrential monsoon rains. According to Pakistan’s National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA), 1,739 people died, including 647 children, and an additional 12,867 people were injured. Around 2.1 million people were displaced and stranded on the streets with no food, shelter, or medical assistance.

This tragedy was unprecedented in terms of its scale and destruction, leaving the country in shambles with the loss of life, livelihoods, infrastructure, economy, and much more. In total, around 33 million people have been affected, with 897,014 houses destroyed and another 1,391,467 damaged. In terms of livestock, 1,164,270 have been killed, most of them in the province of Baluchistan. In terms of infrastructure, due to the destruction of 13,115 kilometers (8,149 miles) of roads and 439 bridges, access across flood-affected areas was vastly hindered. Over 22,000 schools were damaged or destroyed. The country had to declare a state of emergency due to the disastrous situation on August 25. Pakistan had never witnessed such a horrendous scale of devastation, exceeding the destruction caused by the 2010 floods.

What caused this and how did it happen?

As Pakistan receives monsoon rains every year, what changed last year? The year 2022 broke records with high and unusually intense rainfall. Moreover, the country was beset by a severe heat wave during the peak summer months of May and June, which contributed to the melting of glaciers in the North. All these factors inevitably link it to climate change-related vulnerabilities.

The geographical location of Pakistan – at the cusp of the Arabian Sea connecting with the Indian Ocean – makes it susceptible to a higher risk of climate change-induced calamities. With the sea surface temperatures rising and the ocean getting warmer, the increase in torrential rainfall wreaked havoc last year. The scorching heat waves and glacial melting worsened the devastation even further.

Although the whole country bore the burden of this calamitous flooding, the provinces of Sindh and Baluchistan were most affected. Sherry Rehman, the Minister of Climate Change of Pakistan, said that Sindh and Baluchistan received 784 percent and 500 percent more rainfall in the month of August as compared to their monthly averages, respectively. She called it a “climate-induced humanitarian disaster of epic proportions.” She explained: “Needs assessment is being done, we have to make UN’s international flash appeal; this is not the task of one country or one province, it is a climate-induced disaster.”

The UN Secretary-General, António Guterres, while visiting the flood-hit areas was utterly shocked by such a devastating scale of climate-induced destruction. He called it a “monsoon on steroids.” The United Nations issued an urgent appeal for US$160m to provide help. Guterres stated that “Pakistan is a victim of climate change produced by the more heavily industrialized countries.”

Because one-third of the country was submerged in water, the flood-induced damages to infrastructure made it extremely difficult to provide relief aid across the country. The Indus highway in Sindh province, which connects it with the provinces of Punjab and Baluchistan, was inundated by more than half a meter of water. Due to incessant rainfall, flash flooding, and landslides, the dam reservoirs filled up. On the Indus River, which passes through the whole of Pakistan, the Tarbela Dam in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province reached its maximum conservation level of 1,550 feet (472 meters).

Rescuing around 33 million people, including 16 million children, proved impossible. According to UNICEF, 3.4 million children urgently required humanitarian assistance to protect them from drowning, looming waterborne diseases, and malnutrition. Moreover, the estimates indicated that around 650,000 pregnant women were affected, out of whom 73,000 women were expecting to deliver within a month. This extreme calamity will affect many more lives, and unfortunately, its impact will not subside for years to come.

The recovery and relief aid

Since the floods, relief aid and humanitarian assistance has come from various local and international partners – the Government of Pakistan; other countries such as the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Germany, and Saudi Arabia, among others; the European Union and other multilateral organizations such as the World Bank, United Nations agencies, and various INGOs, NGOs, private organizations, and local donors. The data compiled by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) under the revised “Pakistan Floods Response Plan 2022” indicates that, as of April 2023, only 58.4 percent of the total US$ 816.3 million required has been funded. The remaining US$339.8 million needs to be provided. Since every component of the plan remains underfunded, it has critical implications for recovery and rehabilitation.

The Post-Disaster Needs Assessment (PDNA) shows that the total damages were around PKR 3.2 trillion (US$ 14.9 billion) with the total loss at PKR 3.3 trillion (US$ 15.2 billion), whereas the total needs have been estimated to be at PKR 3.5 trillion (US$ 16.3 billion). According to the report, the housing sector suffered the most damage at a cost of PKR 1.2 trillion (US$ 5.6 billion), followed by the agriculture, food, livestock, and fisheries sector at PKR 800 billion (US$ 3.7 billion). The damages for transport and communications stand at around PKR 701 billion (US$ 3.3 billion).

Moreover, the PDNA Human Impact Assessment estimated that Pakistan’s poverty rate may increase by 3.7-4.0 percent, pushing between 8.4 million and 9.1 million people below the poverty line. For the short term, the report recommends prioritizing the provision of social assistance, emergency cash transfers, health services, shelter, and the restoration of local economic activities, especially in agriculture. However, the long-term recovery plan – “building back better” – should follow the policy of “pro-poor, pro-vulnerable, and gender-sensitive, targeting the most affected; strong coordination of government tiers and implementation by the lowest appropriate level; synergies between humanitarian effort and recovery; and a sustainable financing plan.” Besides, the focus also needs to be on building climate resilience, but what about climate justice?

Climate change: adaptation or climate justice?

The issue of climate justice is at the core of Pakistan’s tragedy. If we examine Pakistan’s greenhouse gas emissions, the country’s contribution amounts to less than one percent of global emissions, yet it bears a disproportionate amount of climate-induced calamities. Pakistan has been ranked as the eighth most vulnerable country to climate crisis according to the Global Climate Risk Index. It faces substantially higher rates of global warming as compared to the global average, and it is extremely vulnerable to life-threatening climate crises. This brings us to the ongoing debate on climate justice, which argues that the historical responsibility lies with the global polluters and wealthy countries and should not disproportionately impact the most vulnerable and poor countries, which, relative to the former, do not considerably contribute to climate change.

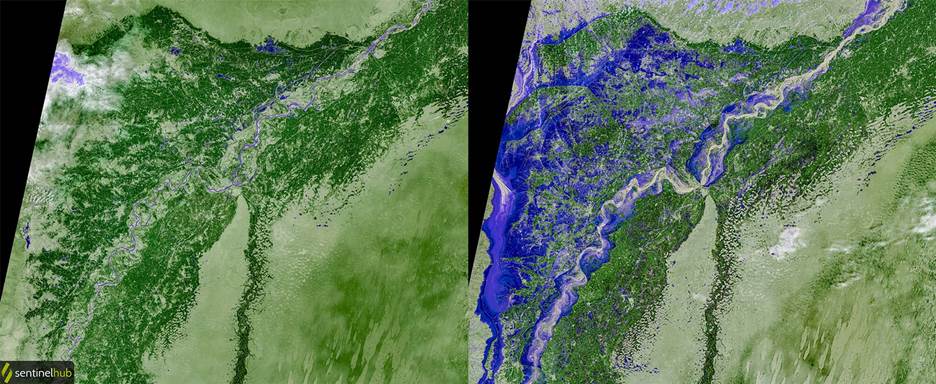

Heavy flooding along the Indus River in Pakistan - Comparison between August 31st, 2021 (left) and August 31st, 2022 (right) - Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons user Pierre Markuse/Sentinelhub

The UN Secretary-General rightly emphasized that since the Group of Twenty (G20) countries is responsible for contributing 80% of emissions, it becomes a moral responsibility for the wealthier countries to aid with recovery and resilience for climate-stricken calamities such as what Pakistan is facing. This also points toward the systemic inequalities and injustices related to the broader Global North vs Global South debate. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report of 2022 puts forth the argument of double injustice. Many developing countries have historically contributed a low percentage of global greenhouse gases (GHGs), but due to long colonial histories, they inherited high levels of vulnerability, development deficits, and structural inequities. Consequently, they are now bearing the burden of global climate change effects. From the climate justice argument, the Global North and the industrialized countries must take more responsibility in proportion to the damage they are causing. As climate change is a global issue that requires global collective action based on a climate justice perspective, vulnerable countries should not be the ones suffering consequences for actions they did not commit.

In a similar vein, Pakistan’s Foreign Minister Bilawal Bhutto-Zardari has been vocal about the issue of climate justice during his national and international media appearances: “Global warming is a global crisis, but its effects are borne by countries which are the least responsible for its causes.” During the 2022 United Nations Climate Change Conference, commonly referred to as COP27, the Loss and Damage fund was set up for climate compensation for poor countries. This is indeed a positive step from the climate justice perspective; however, there is a long way to go in mitigating the irreversible climate-induced damages already incurred. We, as an international community, need to continue the joint efforts for reducing CO2 emissions, and to reach a net zero target for keeping the global increase below 1.5°C.

Way forward

A year later, in the ongoing aftermath of the horrendous flooding, Pakistan still faces a variety of challenges. Amidst escalating inflation, a trade deficit, huge foreign debt, and a lack of foreign reserves, the economic recovery has a long road ahead. As the monsoon rains occur every year in Pakistan, the danger still lingers for this year as well as for upcoming years. So, what can be done to mitigate the risk? What are the shortcomings at the governance level that can be addressed to facilitate the process and prevent this level of catastrophe in the future?

Although immediate relief aid and humanitarian assistance remain an urgent need in the face of such calamities, there must be extensive preventive measures for the future. Pakistan needs to improve its institutional capacities for preparedness and development planning related to disaster risk reduction as well as enhancing the efficiency of response and recovery. It also needs to invest in climate-resilient infrastructure.

Given Pakistan’s dwindling economy and substantial debt, more reliance on loans and foreign aid keeps the country in an unfortunate vicious cycle of dependencies. However, the immediate need for reconstruction related to floods remains a national priority, especially since the summer months are almost upon us. Given the precarious situation, Pakistan would need continuous support from the international community as well as the government and private sector to meet the pressing demands of domestic recovery and fiscal reforms for the long term. It is indeed a humongous task. It is also a tricky balance between carrying out fiscal reforms, improving the efficiency of public spending and revenue mobilization, building climate resilience, and continuing with rehabilitation and protection of the most vulnerable. It is my hope that in the future, better infrastructural setup, urban planning, and river management systems could also facilitate disaster response and recovery.

( Gul-i-Hina van der Zwan is a Research Fellow at International Institute for Asian Studies (IIAS) and Lecturer in International Relations and International Organization (IRIO) at University of Groningen, the Netherlands. IIAS