Debating a Dictator

By Dr Akbar S. Ahmed

American University

Washington, DC

Can you debate with a dictator in public on his home turf? Imagine someone challenging Saddam Hussein or Gaddafi without becoming breakfast for the pet crocodiles the next morning. The debater would have to have their head examined, you would rightly murmur. Yet I did so and lived to tell the tale.

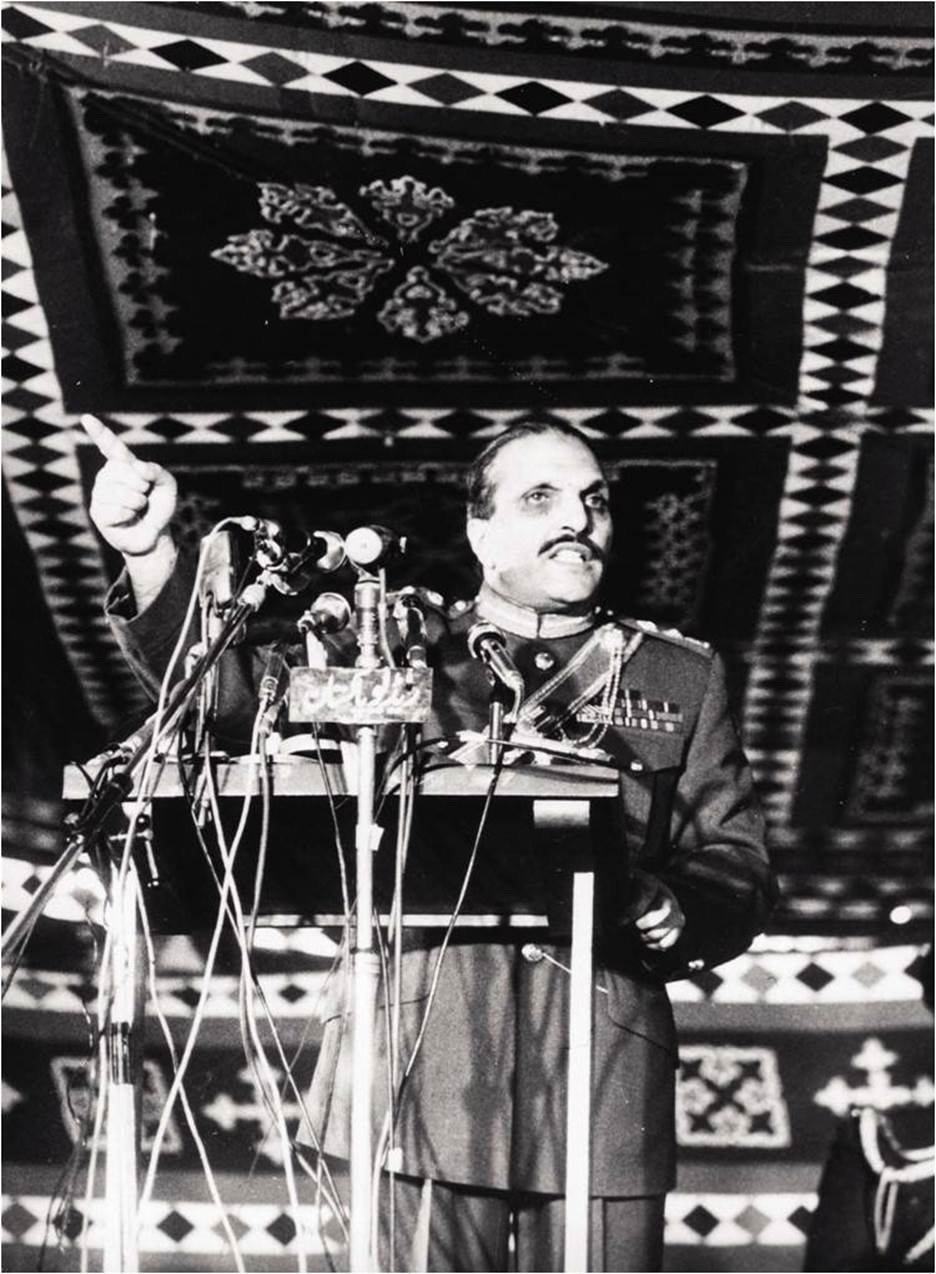

In 1986, I was a member of the CSP, the elite civil service cadre of Pakistan, and Commissioner of the Sibi Division in Baluchistan, when I was invited to come to Multan, one of the famous old cities of Pakistan, to chair the international conference at Multan University organized by the Cultural and Historical Society of Pakistan. As President of the Society, chairing this session was of particular interest because the President of Pakistan, General Zia-ul-Haq, was to be the Chief Guest. This was a high-profile event that would be widely covered by the media, televised and broadcast on the radio. I would speak first, welcoming Zia on behalf of the Society and make some opening remarks, to which he would then respond. This would be followed by a grand dinner, attended by the participants, and these included senior government ministers, ambassadors, heads of NGOs and departments —for example, my American friends, the head of USAID and his wife, were in attendance. Zeenat my wife was with me and observing the proceedings with interest.

This particular session gave me the opportunity to be able to converse with Zia-ul-Huq in a somewhat unique manner and environment where I could actually talk to him, in public, without, hopefully, incurring his wrath. I took the opportunity of my address to raise three questions that, when I look back, were very provocative in the Pakistan context. But the questions had been very much on my mind because after traveling in the Muslim world interviewing scholars and collecting notes for my forthcoming book Discovering Islam: Making Sense of Muslim History and Society, I believed the answers formed the essence of a good and stable society.

It is hardly surprising that Islam should emphasize compassion and humanity in society bearing in mind that the two principal attributes of God, indeed the two greatest names of God, are the Merciful and Beneficent. As for knowledge, ilm, this is the second most used word in the Qur’an and the Prophet (PBUH) had said, “The ink of the scholar is more sacred than the blood of the martyr.” Finally, God in the Qur’an describes himself as the God of the Universes, in the plural.

So, while Muslims have an important place in the chronology of human society, there were also other non-Muslim societies long before Islam arrived. After all Pakistan’s history is based on what is called the Indus Civilization which has a glorious history and there is evidence in the archaeological sites at Harappa, Mohenjo-Daro and Taxila of ancient, sophisticated and complex societies. I felt therefore that these were questions that I could put to the Muslim leader who saw himself as the champion of the faith.

With these three themes buzzing in my head I needed genuine answers as to what was going wrong in Muslim society. So, putting aside my routine cliche-ridden formal address, I said, “Mr President, you’re head of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, and you’re implementing the Islamization of Pakistan. You’re seen as the champion of Islam in the world. Can you then answer me three questions: Firstly, why is the religion which emphasizes compassion and kindness known internationally as the religion of cruelty and violence—its image is that of people’s heads and hands being chopped, of public lashings, women facing honor killings, and so on?”

Secondly, I inquired, “Why is it that the religion of Islam, which emphasizes knowledge, to the point that it is seen as the greatest part and passageway to understanding the Divine, is associated with illiteracy and ignorance? The figures throughout the Muslim world for education are most disappointing and appallingly low.”

I continued: “And thirdly, we are in Multan, where we know that history goes back to Alexander the Great and beyond. Alexander, as you know, attacked the Multan fort and almost died here.

He showed acts of great heroism, and he jumped over the wall into the fort by himself followed by a few companions only, was isolated and almost killed, before he managed to open the doors and get his troops in. So, Multan is part of history. Yet, your philosophy of Islamization preaches that history itself begins with the advent of the Islamic religion and anything before Islam is irrelevant. That is an artificial construct of identity. There was history here, before Islam came. Islam, of course, added to the culture and knowledge and so on. But, there was still an ongoing history, before the advent of Islam.”

Zeenat later said she noted from her vantage point in the front rows that as I spoke Zia picked up a pen and began to scribble in an agitated manner. At this point, the call for evening sunset prayer was heard. So, all proceedings stopped, and Zia got up to offer prayers. We had made arrangements in a small room by the main stage. He left, and we waited on the stage.

As he left for prayers he paused and in an ominously low voice said to me that he would pray to God for the answers to my questions. When he came out of his prayers, he looked me straight in the eyes and smiled, but his eyes were deathly cold. His smile was the smile of the crocodile just before it pounces on its prey. And he said ominously, “You raised three questions, Akbar Sahib, and God has given me the answers.”

At that moment, a chill ran down my spine, and I sensed danger. This was the man who had ignored pleas from all over the world and on the basis of a cooked-up case had executed Pakistan’s popular Prime Minister Z. A. Bhutto in a cold-blooded manner that had traumatized the nation. There were terrible stories of minorities being persecuted and ordinary Pakistanis facing brutal punishment in the name of Islam. That he used the term ‘Sahib’ when addressing me —a word of respect—further unsettled me. It was clear to me that he had taken my questions as a theological challenge, as Islam being attacked, not as a debate within Islam. He had converted legitimate historical questions into an attack on Islam and he would now repel it.

My friends, the head of USAID and his wife, had also sensed the tension. Later that night, at dinner, they told me jokingly, “You asked such provocative questions that we were really concerned. We said, we have to look out for him [i.e. myself] at breakfast – whether he’s even present or not.”

They thought I might be picked up and disappear at night. That’s how serious people thought the questions were. It was a time of paranoia and fear in Pakistan.

But General Zia answered my questions. Standing at the podium in front of the huge audience in the impressive hall, he broke protocol, setting aside his prepared speech to answer my questions.

“Akbar Sahib has asked me these questions, and I will answer them,” he said gravely.

He gave very standard, wishy-washy answers. He claimed, first, there is no cruelty in the Muslim world, only an attempt to impose law and order. There is no such thing as Islam being cruel. People misunderstand: Islam is a religion of peace and compassion.

“Number two, about education, on the contrary to what Dr Ahmed Sahib has just said, we are opening up so many schools and colleges. Our teachers are dedicated and the best. We have done such a good job of opening educational centers everywhere, so you cannot say that education has fallen behind. As regards the third point,” he said, “No! The history of this place begins with the coming of Islam. Islam brought enlightenment, education and brotherhood to a benighted land. There is no history before Islam. It’s blank. Nothing happened before Islam.”

His smile was the smile of the crocodile just before it pounces on its prey. And he said ominously, “You raised three questions, Akbar Sahib, and God has given me the answers” Zia’s answers were a reliable and standard window to the ideas current in much of the Muslim

world. Zia had typically missed the irony of having been invited to address a Society dedicated to the promotion of history. He was dismissing its very foundational principles.

I had questioned General Zia-ul-Haq about core aspects of his Islamization policy, at a public event in Multan. I was, by all means, in perilous waters.

We go back to the essence of this note, which is my own perspective on how closed-minded Muslims see their society and history. I believe it is a failure in the main of the Muslim mind, with some honorable exceptions, to grapple with ideas self-critically and objectively. Muslims should be able to say, “What is going wrong? And how do I fix it?” But we find all too frequently that they are not doing that. They are simply saying, “If something is going wrong, others are making it go wrong.”

True to form the dictator General Zia-ul-Haq would blame outsiders and foreigners for the problems of Pakistan. And in Pakistan, when they say “outsiders and foreigners” they mean either the Indians, the Israelis or the Americans.

I talk of ilm in the ideal. In reality my experience is that the normative attitude to knowledge in society has been generally indifferent and in some cases even hostile. Take this example from my own experience a few short years before that Multan conference where I questioned General Zia.

The file carrying my application requesting study leave to pursue PhD studies in the UK, to which I was entitled, moved 36 times from one level of government to another over two years before I was able to proceed to London. At two points on this long and complicated journey, the file was lodged in a bureaucratic hole and seemed lost but for the intervention of Zeenat’s maternal uncles, who were then members of the shaky provincial government and threatened to pull out of the administration, allowing it to collapse, if the file was not processed. In the other case, the late Hayat Khan Sherpao of the former Frontier Province personally rang the Establishment Secretary, who was known as an inveterate opponent of the CSP and in the habit of routinely rejecting any CSP case, and threatened to take the file personally to the Prime Minister. As Prime Minister Z. A. Bhutto was known to have a foul temper with bureaucrats and as Sherpao was a favorite back then, my file was approved by the Secretary. The PhD process itself was a difficult experience juggling the elements of racism and bureaucracy. When I came back and was posted in the Tribal Areas, I was told by a senior officer not to use the word “doctor” with my name. “The only doctor should be the agency surgeon. You are a CSP officer and do not need a PhD.”

However, judging by the number of doctors today, and especially among women, I can see that progress has been made over the years.

By Pakistanis like Zia denying the past historical legacy of Pakistan, the country ironically loses a rich part of its history. The ancient sites of Mohenjo-daro and Harappa, the quintessential Indus Valley cities, are believed by historians to have had an advanced society – a sewage system, a democratic order (as there was no evidence of large palaces), no priesthood as there were no temples, and inclusive societies that welcomed arrivals from different cultures outside India. In short, the Indus Valley civilization was sophisticated, democratic and multicultural. To dismiss this rich archaeological and cultural heritage because the inhabitants were “Hindus” and not Muslims made little sense.

The attempt to Islamize the past was not simply pedagogical. It had its political roots in India where there was an increasing movement towards glorifying the pre-Islamic past. Historians, polemicists and journalists were conjuring a time of such marvels as helicopters, missiles and brain surgery that could compete with the best the modern world had to offer. The subtext was simple and clear. India was a highly advanced and integrated civilization until its purity was violated with the arrival of the corrupted and corrupting Muslims. For this purpose, Muslims were depicted not unlike Donald Trump’s description of Mexicans arriving in the US – rapists and murderers. Reading current textbooks gives us evidence of the widespread revision of history that is taking place. Muslim rulers are dismissed as drunken buffoons lusting after Hindu women. Their achievements and accomplishments are rarely, if ever, mentioned.

Even Akbar the Great, once the favorite of British and Indian writers for his generosity and inclusiveness towards non-Muslims especially Hindus – contemporary accounts in the celebrated Akbar Nama about his reign confirm this – has been denounced by a BJP minister and others as a Hitler and a fascist. Place and street names honoring Muslims are being replaced.

This subtext of the predatory and alien Muslim in India had grown and spread into the mainstream. There would come a time when the stabbing to death and lynching of ordinary Muslims on their way to perform routine chores would become so common as to barely cause comment. The entire community was guilty – as eaters of the divine cattle and therefore culpable. As a consequence, Muslims were openly vilified in the media and faced discrimination.

Even well-known Muslim movie stars were denied flats and houses for rent because of their faith. Inevitably there was a correlation between the spread of communal ideology and politics.

Starting from virtually zero in Parliament – the association with Nathuram Godse, a member of the right-wing RSS who assassinated Gandhi in 1948, affecting their popularity – the BJP exemplified right-wing ideology and aggressively supported the idea of the Hinduization of India. Over time, it gained sufficient support in parliament to win the government. By the 1990s it had its first prime minister in Delhi. PM Narendra Modi, a hardcore BJP supporter forever tainted with the 2002 massacre aimed at Muslims when he was head of government in Gujarat State, is a product of this background.

We have to be cautious of generalizations, however. The right-wing was not a monolith: as the examples of leading BJP members A. B. Vajpayee, L. K. Advani and Jaswant Singh illustrate. They could look at Muslims, Pakistan and even the Quaid-i-Azam at certain periods of their lives with more discernment than others of their ilk.

Zia and people who think like him in Pakistan then represent a mirror image to these right-wing developments across the border. In Pakistan, textbooks depict Hindus normatively in a negative light. The very word “Hindu” in society especially in the villages generally signifies an unclean and lowly person. In Pakistan the notorious case of Asia Bibi highlighted the prejudice and dangers that minorities face. While drinking water at the village, she was accused of violating the purity of the utensils – a cultural practice influenced by notions of Hindu castes – and in the argument that followed, accused of blasphemy. She was quickly ensnared in a nightmare and sentenced to death. A perfectly innocent woman was incarcerated for a decade waiting to be put to death when a hearing of the Supreme Court found her innocent in an appeal and ordered her to be freed. In the meantime, numerous lives had been lost, including that of the Governor of Punjab Salmaan Taseer and federal minister Shahbaz Bhatti, in the passions aroused by the Asia Bibi case. Such was the level of irrationality that the killer of the Governor, a member of his bodyguard, became a folk hero – with thousands hailing his lawyers as saviors of Islam.

These South Asian societies are convulsed in palingenetic narratives.

My questions to Zia, however, were not situated in the Indian-Pakistani context although they had lessons for both. They were more philosophical and pedagogical in nature and related to the larger Muslim world. Without rigorous academic research and interpretation, the past can all too easily be manipulated into ideological shapes that suit the politicians of the time. It leads us into the trap of creating a totally imaginary past. In the context of South Asia, it also has a deadly corollary – if our community is pure and the other impure and therefore evil, we must attack it and attempt to remove it.

Ironically, very similar, ugly and distorted mirror images of the Other have developed in India and Pakistan. Inevitably this distortion of facts and the creation of an imagined past have affected communal relations and violence has followed. Minorities in India and Pakistan, especially Muslims in the former and Hindus in the latter, have suffered egregiously.

Not long after my encounter with General Zia in Multan, appreciating that discretion is the better part of valor, I accepted the Iqbal Chair of Pakistan Studies at Cambridge University and in 1988 headed for the safety and sanctuary of a Western university.

Emma Duncan, who worked for the Economist, provided an explanation of how I had got away with my ideas so far in her contemporaneous book on Pakistan, Breaking the Curfew (1989):

“Akbar Ahmed is the commissioner of Sibi, and an anthropologist with impeccable academic credentials: Harvard, Princeton and Cambridge, and a list of well-reviewed books as long as your arm. His survival in the civil service is a remarkable tribute to his brains. Although an intellectual, he is regarded as an asset, not just because he writes about Islam and Islamic anthropology, but because his talents are recognized internationally. His book-launches, he told me, are big events, attended by ministers and ambassadors. His social pedigree is equally smart. Meeting his wife, you understand the meaning of breeding, in the nineteenth-century sense. The granddaughter of the last Wali of Swat, she has a calm, reserved beauty that demands no tributes” (p. 136).

It was the same degree of protection from Zia’s anti-intellectual regime, and his spirit of retribution, that allowed me to survive after Multan. It would be another decade and the behavior of another benighted dictator which would lead me to sending in my request for early retirement from the service. Disgusted with the shenanigans that I confronted in the leaders and bureaucracy of Pakistan, I retired in self-imposed exile to the USA to spend my time on campus. Once there, the students, the research and the debates around Islam kept me happily occupied. I was done in dealing with egomaniacal dictators who stifled independent thought, reveled in ignorance, and promoted cruelty in the name of my faith. New debates and new challenges awaited me in the US.

I had got a new lease of life and, most importantly, a platform to continue my attempts at disseminating the permanent and inclusivist ideas of Islam, especially where they overlapped with other cultures and religions. I felt that we still had something significant to contribute to human civilization, especially with a view to the greater global crises that faced it. It also allowed me to explore and discover more fully the wonders that lay in the faiths and cultures of others. In short, to become a bridge-builder between cultures and religions.

It gave me a golden opportunity to become once again a seeker and a student.

(Akbar Ahmed is the Ibn Khaldun Chair of Islamic Studies, School of International Service, American University, Washington DC. He is a Wilson Center Global Fellow. He was the former Pakistan High Commissioner to the UK and Ireland and in 1970-71 was Assistant Commissioner in East Pakistan.)