Iqbal was the exponent of human Essence, the voice of human longing to find God through history. Faiz was the poet of human love, the voice of der angst, the human agony in its separation from God. Two great men, two great souls, two poets without whom Urdu poetry would not be the same, two stars illuminating the canvas of human history with their light, a light reflected through Noor e Muhammadi, the Light of Existence

From Iqbal to Faiz: Essence and Love in Urdu Poetry - 2

By Professor Nazeer Ahmed

Concord, CA

Iqbal, a keen student of Qur’anic teachings, knows that Khudi applied not just to individuals, it applied to spiritual communities (Ummah) as well. The Qur’an declares, “We have fastened your fate (O humankind!) around your own neck.”

Each individual has an Essence. That is the individuality of men and women. Similarly, every community, and every nation, has its Essence. It is in the concept of Khudi that one has to find his political views that so dominated the last third of his life. A people must have the freedom to find their Khudi, their Essence and to express it on the stage of human history, just as an individual must have the freedom to find his Essence and express it in the matrix of human affairs.

Iqbal, the poet cannot be separated from Iqbal, the politician and statesman. Iqbal was deeply concerned about the condition of his own Muslim community in a milieu where they were a numerical minority. Through a careful and thorough analysis of the dynamics of Islam, documented thoroughly in The Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam, he concluded that ijtihad was the moving principle of Islam. He agreed with the Turkish poet Zia that an elected legislature representing the masses, as opposed to an individual, was in the best position to exercise ijtihad in modern times. Then he came to the momentous and fateful conclusion: “In India, however, difficulties are likely to arise for it is doubtful whether a non-Muslim legislative assembly can exercise the power of Ijtihad”.

This led him to propose the idea of a separate state for the Muslims of the northwestern states in British India, an idea that was the precursor for Pakistan. The demand for an independent state in northwestern British India was not an expression of separatism but a positive statement of the Khudi of a people. Iqbal envisaged legislative autonomy so that the people of the Punjab, Sindh, Northwest Frontier and Baluchistan might discover their essence and participate in the majestic march of human civilization.

The important lesson here is that Iqbal was not just a poet, a thinker and a dreamer; he was a man of action. He was willing to take the risk of injecting himself into the process of history, knowing full well that great ideas are compromised and often despoiled when they are implemented in the matrix of human affairs. Whether a Pakistan that came into being lived up to or did not live up to Iqbal’s ideals is no reflection on his ideals.

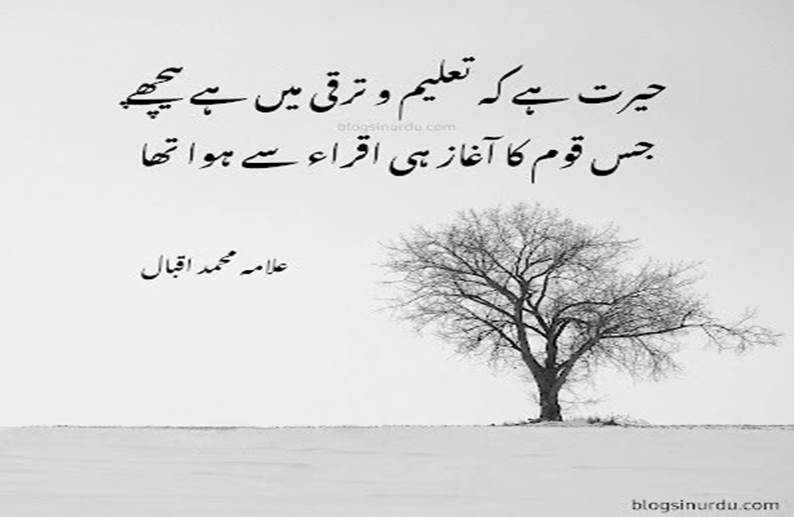

Faiz Ahmed Faiz stands in contrast to Allama Iqbal both in style and substance. As a young man, he studied and was influenced by the material dialectic of Marx and Engel. The exploitation of the masses in British India convinced him that only a revolution could restore the balance of justice. As a young officer in the British Indian army, Faiz was witness to the corruption and rapacity of the money lenders, hoarders and landlords in the great famine of 1943. The ruling Unionist party in his home state of Punjab, a motley conglomerate of sajjada nishins of zawiyas, gurus of temples and gurdwaras and a rapacious merchant class did nothing for the poor peasants and the toiling masses. Faiz was witness to the holocaust that accompanied partition when hatred engulfed the vast plains of the Punjab and human bestiality found a free expression rarely witnessed by humankind. These were the formative years for Faiz, and they reinforced his conviction that justice and love were the only antidotes for the der angst felt by humankind in its march through history. Faiz thus became the poet of justice and love just as Iqbal was the poet of essence and destiny.

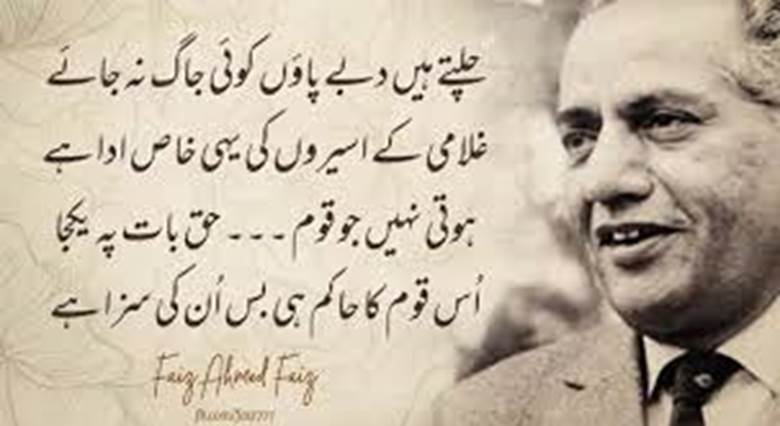

It was through the publication of Daste Saba and Zindan Nama, both written in prison from 1951 to 1955 that the world came to know of Faiz. It was in the dungeons of Punjab that Faiz found his voice. While his feet were shackled, he wrote from his soul,

Mata e looh wa qalam chin gayee tho kya ghem hai

Ke Khoon e Dil mein Dubo dee hain unglian mein ne .

(Grieve not that the Pen and the Tablet are denied thee,

I have dipped my fingers in the love of my heart.

Notice that Looh wa Qalam (the Tablet and the Pen) serve different functions for Iqbal and Faiz. Iqbal said:

Yeh Jehan cheese hai kya looh wa qalam tere hain

(This world? What is its worth?

To you belong the Tablet and the Pen).

The pen and the tablet are tools in the hands of Iqbal to discover human Essence and human destiny. For Faiz, they are inconsequential; he writes his destiny with the love of his heart. I have deliberately translated Qoon as love in the tradition of Imam Razi, the 10th century savant for whom blood meant the essence of the heart through which God distributes his mercy to all parts of the body, mind and the soul. If you take the literal translation of qoon as blood, you see the revolutionary zeal of the poet, in that history will be written in the blood of the martyrs.

Iqbal reaches yet another height when he declares in Bal e Jibrael:

Looh bhi tu, Qalam bhi tu, tera wajud al kitab

(You are the Tablet, you are the Pen, your existential Essence is the Book)

Here Iqbal reaches the station of Ibn al Arabi. This line of thought must stop here because it is beyond the scope of this brief paper.

The creative genius of Faiz Ahmed Faiz was to integrate in his poetry his vision of justice and love. The agony of humankind, oppressed as it is with the burden of time, is highlighted, but it is done not with hatred but against a background of the sweet music of love. The heart of Faiz bleeds with sorrow, but what it sheds are tears of love.

VIt takes enormous compassion, forgiveness and charity to love the hand of the oppressor. While the tongue of Faiz is the tongue of the oppressed, the heart of Faiz is the heart of the lover. In this he stands in the same league as Hafiz who witnessed the destructions of the Timurid invasion of Asia towards the end of the fourteenth century, yet sang of the sublime love that transcends hate and oppression.

Dono Jehan Teri Muhabbat me haar ke

Woh ja rha hai koyi shab e gham guzaar ke

(There goes one, having spent the night of sorrow,

For your love, he lost the here, and he lost the hereafter).

The search of Faiz led him to the conclusion that love alone was the solution to man’s condition. But he left the idea of love dangling between heaven and earth. That is why you find in his poetry an unceasing longing (Ishtiaq), a burning desire for the beloved.

Iqbal’s poetry leaves you satisfied and spurs you to action. It is like a laser beam trained to perform surgery; Faiz’s poetry, like unrequited love, leaves you longing for more. It is like uncontained fire that burns. Iqbal and Faiz are like two travelers in the desert, one is guided by a distant star, the other abandons his quest to the love of his heart and is content to cry out in the desert. Both reached heights of imagination attained only by a few. “I offered the trust to the heavens and the earth,” declares the Divine Word, “they declined, being afraid thereof. But man accepted it. He was indeed ignorant.” Why did man accept the trust? Rumi answers it by saying that man was drunk with love and he did not know what he was doing. That love was infused into the Ruh of man when divine love breathed it into the spec of dust that was Adam. Iqbal and Faiz were both drunk with love, and like Adam, they were on earth searching their own way back to God. Iqbal searched, concluded, took a chance and formulated a solution. Faiz sailed through the same oceans, reasserted the love that animates man’s search, but he left it at that, satisfying himself with a direction dictated by the material dialectic of man.

Iqbal tries to decipher the will of God and finds it reflected in the will of man. Faiz tries to decipher the will of God and finds it in the love of man. The suspension between heaven and earth gives his poetry an ethereal quality that leaves one longing for more. Iqbal’s work has the ethereal quality but it is firmly tethered to the throne of God and the world of man.

Faiz’s poetry presents a paradox. He is the poet of justice and love but seeks its fulfillment in a material dialectic. This dichotomy requires a deeper understanding of Faiz and the essence of his poetry. Love is a bourgeois feeling; indeed, it is the core of religious experience. How could one be both a Marxist and a lover? One possible explanation is that Faiz, despite his Marxist orientation, remains deeply attached to his Qur’anic roots. Zulm and its redress run as a continuous thread in the Qur’an. One of the 99 divine names is al Haq, meaning Justice. Faiz’s poetry searches for Haq. God will hide all sins on the Day of Judgment, says the Qur’an, except Zulm. It will speak up and the Zalim will be punished. When Zulm does speak up on the Day of Reckoning, I am convinced one of the voices that will speak up for the Mazloom masses will be the voice of Faiz Ahmed Faiz.

Uthe ga Anal Haq ka naara,

Jo mai bhi hoon aur tum bhi ho;

Aur raj kareg khalq e khuda,

Jo mai bhi hoon aur tum bhi ho.

(The cry « here is justice » shall resound,

I shall be there, so will you,

And the servants of God (the people) shall rule,

I shall be there, so will you.

In accepting the Lenin Prize in Moscow in 1962, Faiz said: "Every foundation you see is defective, except the foundation of love, which is faultless.” It takes moral courage to love even when you see the ugly face of tyranny and have felt its heavy hand on your personal self. Faiz demonstrates that moral courage. It is in this moral courage as well as the enduring value of love that one has to look for the greatness of Faiz Ahmed Faiz.

However, Faiz was no social reformer. As a poet, he was the universal voice of the oppressed. He sought redress for injustice in a material dialectic which has since been discredited. His poetry, with its universal appeal to justice and love, transcends his culture and is accessible to all humankind cutting across religion, race, nationality and time. By contrast, Iqbal was a poet, a thinker, a social and political reformer who stayed within his tradition and sought to expand its envelope to include all humankind. He was a risk taker who injected himself into the process of history and was willing to face the failures and disappointments that are all too characteristic of human effort. Iqbal was a man of action and it was through action that he sought to discover the Essence of man. Faiz was a mirror which showed the contorted face of zulm. It was an ugly face but even while he looked at the ugly face, he saw the beauty behind it and fell in love with it.

In conclusion, Iqbal was the exponent of human Essence, the voice of human longing to find God through history. Faiz was the poet of human love, the voice of der angst, the human agony in its separation from God. Two great men, two great souls, two poets without whom Urdu poetry would not be the same, two stars illuminating the canvas of human history with their light, a light reflected through Noor e Muhammadi, the Light of Existence.

(The author is Director, World Organization for Resource Development and Education, Washington, DC; Director, American Institute of Islamic History and Culture, CA; Member, State Knowledge Commission, Bangalore; and Chairman, Delixus Group)