Mighty emperors like the Chinese Ming ruler and famed scholars like the German philosopher Goethe, alongside celebrated Muslim scholars and mystics like Rumi, Ibn Arabi and Iqbal would write panegyrics in verse in his honor. Thomas Carlyle has an entire chapter on him, the Prophet as hero, and he becomes the second subject of Carlyle’s lectures after the first one on gods. Napoleon in Cairo was so impressed by the Prophet and his religion that he declared he had accepted the faith. He was even said to have taken the name Ali, after the son-in-law of the Prophet

“A Mercy unto Mankind”

A Dedication to the Prophet (pbuh) from East to West

By Dr Akbar Ahmed

American University

Washington, DC

When the Prophet of Islam, (peace and blessings on him), returned to Mecca at the head of a large victorious army the people of that city waited anxiously for what he would do to them. They had planned assassination attempts, thrown garbage on him, and taunted and insulted him at every turn. They had even killed his beloved uncle Hamza in a cruel and notorious manner.

Hamza was known for his generosity and nobility of character. If they could not get to the Prophet, his enemies understood that by removing Hamza they would hurt and harm the Prophet. Wahshi bin Harb, the Abyssinian slave-warrior therefore had been tasked with killing Hamza and in return promised freedom. Wahshi tracked Hamza like a hunter pursuing his prey, killed him and then sliced his body so that he died a painful death. Then

Hind, belonging to the aristocratic Quraish who were vigorously opposing the Prophet and his message, cut out Hamza’s liver and chewed it in public to show her contempt for the Prophet. So, when the Prophet declared a general amnesty, the citizens of the city were relieved. But they wondered what the Prophet would do to Wahshi and Hind.

When the Prophet asked to see Wahshi and Hind, the people of Mecca expected that the customary laws of revenge would prevail. They were sure that these two would receive the most severe punishment possible and according to the laws of revenge it would surely be death. When Wahshi and Hind appeared before the Prophet in trepidation they were surprised he did not order their execution on seeing them. The Prophet explained why he asked to see them. You were the last to see my beloved uncle Hamza alive. I wanted to hear from you everything about him in the last moments of his life. As the two recounted the story of Hamza's death, the Prophet’s eyes filled with tears. It is said that he found the recounting of the killing of his beloved uncle Hamza by Wahshi so painful that he asked Wahshi to stop the narration.

To hear of the pain and humiliation Hamza went through was almost unbearable for the Prophet. Yet he forgave them. After a pause, though, he had a request. He asked Wahshi to avoid crossing the Prophet's path as seeing him would remind the Prophet of his beloved uncle and the painful manner in which he had died which may provoke anger in the Prophet. Avoid walking in front of me or crossing my path as every time I see you, I will be reminded of the death and circumstance of my uncle’s last minutes on earth. That would be too painful for me.

Wahshi and Hind could not believe their luck. They had gone to the meeting convinced it would be their last. Now they were free to go. Not long after both converted to Islam. Wahshi made his name fighting the enemies of the Prophet and Hind's family served Islam.

The Prophet’s life had seen many trials and tribulations. But it was also one of dizzying triumph. Within his lifetime, he had successfully introduced a new religion based in compassion and justice to the world. He had led armies, been a loving husband and father, and a law giver –---an aspect which would be recognized by the Supreme Court of the US and Lincoln’s Inn in London. And within four years of his passing, Muslim armies would defeat the two greatest empires of his time –-- the Romans and the Persians.

The life of the Prophet was also important for providing us with some of the most extraordinary figures in history. These figures included such names as his celebrated wife and rock of support Khadija; his cousin and son-in-law, the heroic warrior-scholar Ali of whom the Prophet said, “I am the city of knowledge, and Ali is its gate;” Fatima his saintly daughter married to Ali; their son, the champion of the oppressed, Husain, who was martyred at Karbala; and their daughter Zainab who survived Karbala to become an iconic role model for women everywhere. They were – and are – superstars in the Islamic firmament.

Mighty emperors like the Chinese Ming ruler and famed scholars like the German philosopher Goethe, alongside celebrated Muslim scholars and mystics like Rumi, Ibn Arabi and Iqbal would write panegyrics in verse in his honor. Thomas Carlyle has an entire chapter on him, the Prophet as hero, and he becomes the second subject of Carlyle’s lectures after the first one on gods. Napoleon in Cairo was so impressed by the Prophet and his religion that he declared he had accepted the faith. He was even said to have taken the name Ali, after the son-in-law of the Prophet. Celebrated Hindu spiritual leaders like Vivekananda called the Prophet a “world mover” and Mahatma Gandhi described the sayings of the Prophet as “the treasures of mankind.” Parents across the world would name their sons Muhammad, Ahmed, Mehmet, or Mustafa after him.

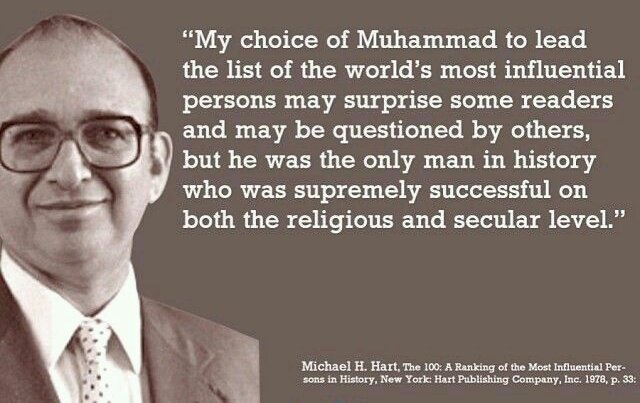

Authors sometimes cannot resist the temptation to make lists of the inspirational figures of history and rank them. One of the well-known books of this kind was written by an American professor called Michael Hart. His book was simply titled The 100: A Ranking of the Most Influential Persons in History (1978). It gave the names, as the author saw them, of the hundred most important men and women in history. What he had done was rank these historical figures. The question immediately arises as to who is number one? Who is the most important figure in human history? There are several candidates that come to mind. Jesus, Buddha and Moses are obvious religious choices. “What about Marx and Lenin?” say the socialists. “Adam Smith and Henry Ford,” shout the other side. “What about me as the greatest?” yells Muhammad Ali. But no, the number one choice, and the author gave his reasons why he had made it, was the Prophet Muhammad (peace and blessings upon him.) A few years later, Hart revised his book to update the list. Once again. the Prophet of Islam was selected as the most influential person in history.

A few years later, Hart revised his book to update the list. Once again. the Prophet of Islam was selected as the most influential person in history – Twitter

Tributes are recorded from across the Muslim world, from the high and mighty to the peasants in their fields. But the tributes by non-Muslims are especially noteworthy. I am reproducing the poems by the Chinese Emperor and the German philosopher as a neat dedication from the East and the West by non-Muslims. I suggest the reader enjoy them in full to appreciate their impact as having been written by non-Muslims.

From the East we have the First Hongwu Emperor of the Ming Dynasty. Below, we present the extraordinary poem The Hundred-Word Eulogy written by the Emperor in honor of the Prophet, and engraved on some of the oldest mosques in China.

The Hundred-Word Eulogy

by the Hongwu Emperor of the Ming Dynasty (r. 1368–1398)

From the beginning of the Universe,

Heaven has already appointed

The Great Sage born in the West,

who transmits and teaches.

He received Heavenly Scripture

In a thirty-part book,

To guide all creatures.

Master and teacher of myriads,

Leader of countless sages,

With support from the Divine,

To protect his nation’s people

With five daily prayers,

Silently wishing for peace.

With his heart toward the True Lord,

Inspiring the poor ones,

Saving them from calamity,

Seeing through the Unseen,

Redeeming souls and spirits,

From all wrongdoings.

A mercy to the world,

Leading the Path for the past and the

present,

Reducing evil to the One.

The name of his teaching: Pure and True.

Muhammad, the most noble sage.

From the West we have Goethe the great German poet-philosopher. In European literature Goethe combines the dramatic genius of a Shakespeare and the philosophic scope of a Socrates and Plato. Goethe’s brilliant poem called Mahomet’s Song in honor of the Prophet contains sparkling images and joyous verses that take the breath away. The poem is so passionate in its reverence and love for its subject that we are tempted to suspect that the poet is in fact a Muslim.

Mahomet’s Song

By Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832)

(Translated by J. S. Dwight)

See the rocky spring,

Clear as joy,

Like a sweet star gleaming!

O’er the clouds, he

In his youth was cradled

By good spirits,

’Neath the bushes in the cliffs.

Fresh with youth,

From the cloud he dances

Down upon the rocky pavement;

Thence, exulting,

Leaps to heaven.

Goethe’s brilliant poem called Mahomet’s Song in honor of the Prophet contains sparkling images and joyous verses that take the breath away

For a while he dallies

Round the summit,

Through its little channels chasing

Motley pebbles round and round;

Quick, then, like determined leader,

Hurries all his brother streamlets

Off with him.

There, all round him in the vale,

Flowers spring up beneath his footstep,

And the meadow

Wakes to feel his breath.

But him holds no shady vale,

No cool blossoms,

Which around his knees are clinging,

And with loving eyes entreating

Passing notice;—on he speeds

Winding snake-like.

Social brooklets

Add their waters. Now he rolls

O’er the plain in silvery splendor,

And the plain his splendor borrows;

And the rivulets from the plain,

And the brooklets from the hillsides

All are shouting to him: Brother,

Brother, take thy brothers too,

Take us to thy ancient Father,

To the everlasting ocean,

Who e’en now with outstretched arms,

Waits for us,—

Arms outstretched, alas! in vain

To embrace his longing ones;

For the greedy sand devours us,

Or the burning sun above us

Sucks our life-blood; or some hillock

Hems us into ponds. Ah! brother,

Take thy brothers from the plain,

Take thy brothers from the hillsides

With thee, to our Sire with thee!

Come ye all, then!

Now, more proudly,

On he swells; a countless race, they

Bear their glorious prince aloft!

On he rolls triumphantly,

Giving names to countries. Cities

Spring to being ’neath his foot.

Onward, with incessant roaring,

See! he passes proudly by

Flaming turrets, marble mansions,

Creatures of his fulness all.

Cedar houses bears this Atlas

On his giant shoulders. Rustling,

Flapping in the playful breezes,

Thousand flags about his head are

Telling of his majesty.

And so bears he all his brothers,

And his treasures, and his children,

To their Sire, all joyous roaring,

Pressing to his mighty heart.

I am also including my own humble dedication to the Prophet in the form of a poem called The Night Journey. The Night Journey is an event celebrated enthusiastically every year by Muslims throughout the world.

The Night Journey

My name is Buraq

From lightning or radiance

And I am both;

Half-angel, half-horse, half-bird

I am not an angel nor a horse

Yet I am both.

Poets have written verses

about the beauty of my face

The luminosity of my eyes

and the span of my wings

which is that of an angel.

One night there was a rustling and swooshing

And before me stood the majestic figure

Of the archangel Gabriel.

He had a special mission for me.

Not accustomed to command

I bucked and snorted.

Then Gabriel chided me gently,

“No one is more beloved of God

In all creation

than the one you are to carry

to the presence of the Lord.”

My passenger was none other

than the Seal of the Prophets,

the Beloved of God,

the insan-i-kamil.

As the enormity of the task sank in,

and the magnificence of the honor,

sweat poured over my body.

When the beloved of God was summoned

From on high

we left from the Kaaba in Makkah

to the noble sanctuary in Jerusalem

the holy Prophet joined the others beloved of God,

Abraham, Moses and Jesus,

in prayer

and we then ascended to the heavens

all the while accompanied by angels

and guided by the venerable Gabriel himself.

Planets and stars orbited around us

suns and moons set and rose in front of us.

I saw the moons of Jupiter

Dance on its shoulder

And beams from distant planets

almost threw me off my course

There was a sublime silence

that filled every corner of the universes

and a million stars sparkled around us.

When we had crossed the seven skies

and the seven heavens

we arrived in the presence of the Almighty.

The brightness around Him

Was that of a thousand suns

a sight I had never seen

and yet a blissful calm permeated everything.

There the messenger of God

took instructions from the Almighty.

Then we turned and began the return journey

Creation and creator had met

worshipper and worshipped had

come face to face

even I knew the magnitude

of what had happened.

Poets would sing

about this night journey, Shab-i-Miraj,

painters capture it in their imagination

and every year

worshippers would pray in its memory

but nothing could compare to what I saw.

Yet

The savants argue interminably

With rulers and maps

Round and round

’till I get a headache.

Fools…

There are more things in heaven and earth

than are dreamt of in your philosophy.

The hand of the holy Prophet

brushed against a glass of water

and he reached for it–

between the time the glass began to fall

and he caught it

we had completed our travel;

space and time were compressed

into a fleeting moment.

My name is Buraq

I am unique in the heavens

and legendary on earth

for I carried the Beloved of God

to the seventh heaven

and brought him back safely.

For me the Prophet’s treatment of Wahshi and Hind sums up the essence of the man. When an individual can control his anger or thirst for revenge and convert it into an act of compassion, he has mastered himself. The Prophet had emphasized forgiveness as a virtue, and he was addressed as a “Mercy unto mankind” in the Qur’an. In this episode from his life, he illustrated the meaning of his title.

Yet his name today evokes hostility in certain situations among non-Muslims. This is certainly true in what I experienced. I felt this high tension and humiliation on nearly every flight I took in the US after 9/11. Every time I walked up to the airline counter and presented my ticket, a glazed look came over the face of the airline official. Discreetly a phone was picked up. I was politely told to step aside and asked questions about my identity and what I was doing in that city—and why I was flying. Nothing that identified me seemed to matter except that my name was “Ahmed”. I was assumed guilty and had to prove my innocence.

I recall one incident in particular because of how explicit it was at Reagan National Airport in Washington DC. I was flying to a university in the Midwest to lecture on promoting better understanding between Muslims and Americans. I was already pre-checked and had my boarding pass. I stopped an official of the airline to ask about the security gate. She was a friendly African American woman. She smiled and said no problem, but then she looked down at my boarding pass. There was a flicker of recognition on her face as she saw my name, Ahmed. She said “oh no, you must come to the counter and check in there before proceeding to the security gate.” I asked her why, as I had already obtained my boarding pass. What did she see that necessitated this scrutiny? “Is it because of my name Ahmed?” I asked. She nodded in sympathy as she proceeded to type in my name, make discreet phone calls and start the procedure to check whether I was on some no-fly list. My age, profession, and status did not matter. My name was Ahmed and that was sufficient to alert the system and merit scrutiny. Perhaps we Muslims could have done a better job in explaining the principles of our faith to non-Muslims. But any Muslim approaching any official counter in the West will feel the lack of understanding as I did.

On such occasions which perhaps involved overt forms of racism and religious prejudice, I was tempted to give a lecture on the meaning of the word Ahmed. The name meant “highly praised” and was an esoteric name for the Prophet of Islam. It was a derivative of Muhammad, the popular name of the Prophet. Muhammad, Mustafa, Ahmed, these were the names of the Prophet whom Muslims blessed him as “Mehboob -e-Khuda,” or the “Beloved of God” and “Habibullah” or “Friend of God.” His names contain the most beautiful human attributes, and every time Muslims mention them, they add the words “peace and blessings be upon him.” The name of the Prophet is also one of the most popular throughout the world. “It is number one for boys in the UK,” we were told during our fieldwork trips there, and it is especially popular in Muslim lands. My father’s name was Muhammad Salahuddin Ahmed. Yet here in the United States, Ahmed could attract negative attention.

World-shaking revolutions are protracted and bloody affairs that alter the lives of millions and herald a new order. The French revolution in the late 18th century, the Russian revolution in the early 20th century, and the Chinese and the Iranian revolution later in the same century were all world-shaking violent events that turned the established order upside down. In sharp contrast, the Islamic revolution led by the Prophet of Islam, which in its significance was no less world-shaking than the other revolutions, was conducted with virtually no loss of life. By declaring a general amnesty, the Prophet had anticipated and resolved the tribal compulsion for vendetta and revenge. In his celebrated Last Sermon at Mount Arafat, he declared an Arab was not superior to a non-Arab, nor a white man to a black man; and that a person will be judged only by their piety and good action. In his life and actions, the Prophet had emphasized justice, compassion, the pursuit of knowledge and enquiry, and a broad embrace of humanity. There are lessons there for both Muslim and non-Muslim societies in our own troubled times.

(Akbar Ahmed is the Ibn Khaldun Chair of Islamic Studies, School of International Service, American University, Washington DC. He is a Wilson Center Global Fellow. He was the former Pakistan High Commissioner to the UK and Ireland and in 1970-71 was Assistant Commissioner in East Pakistan.)