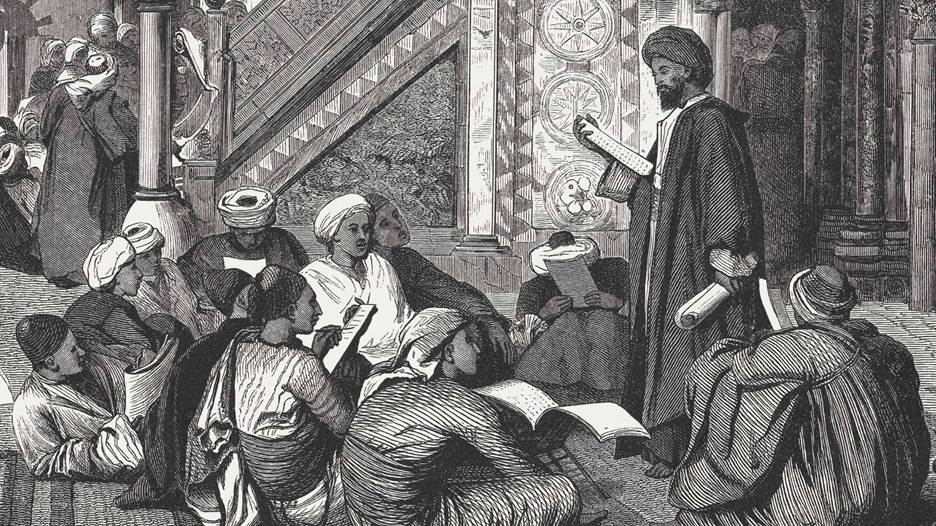

It comes as a surprise to some readers that the American National Anthem, The Star Spangled Banner, was inspired by the rockets invented by a Muslim king, Tippu Sultan of Mysore – Photo Yaqeen Institute

Why Did the Scientific Revolution Not Take Place in the Islamic World?

By Professor Nazeer Ahmed

Concord, CA

Summary: The natural sciences did not die out in the Islamic world with the Mongol devastation of the thirteenth century. Indeed, the Muslims held their own in art, architecture, astronomy, and artisanship on the world stage well into the seventeenth century. It was only in the eighteenth century that Europe acquired a decisive technological edge and supplanted the ancient civilizations of Asia and Africa.

This article examines the complex interplay of intellectual, religious, social, political, economic factors and the decisive military events that precluded the onset of a scientific revolution in the Islamic world. Summarily, we find seven discernible milestones in the 1400-year history of Muslims that influenced the development of science and technology:

- The Mu’tazalite eruption and its aftermath (765-846)

- Al-Gazzali’s repudiation of the philosophers (1100)

- The Crusades (1096-1240)

- The Mongol Devastations (1219-1258)

- Neglect of the printing press and naval technology (1450-1728)

- The Destructive Shia-Sunni, Sufi-Salafi Controversies (700-ongoing)

- Colonialism and the onset of the Age of Discontinuity (1757-1947)

The discourse tends to get obscure when questions of philosophy and science are discussed. Therefore, a number of resources from the open literature have been used to construct a narrative that is as accessible to a layman as it is to a scholar.

The Rockets of Mysore

It comes as a surprise to some readers that the American National Anthem, The Star Spangled Banner, was inspired by the rockets invented by a Muslim king, Tippu Sultan of Mysore, India. It was the year 1814. The Anglo-American war was in full swing. The British forces, after burning down Washington and conducting a raid on Alexandria, proceeded up the Chesapeake Bay to capture Fort McHenry in Baltimore. Caught in the crossfire were two American lawyers, Francis Scott Key and John Stuart Skinner who had gone over to negotiate a truce and prisoner exchange with the British. Key and Skinner were allowed to board the British flagship HMS Tonant and present their proposals to Major General Robert Ross and Vice Admiral Alexander Cochrane while the two were discussing their plans for an attack on Baltimore.

Since they had overheard the detailed war plans, Key and Skinner were held back by the British and were witness to the bombardment of Baltimore on September 13, 1814. Orange and red flashes of rocket fire illuminated the skies over Fort McHenry. The stillness over Chesapeake Bay was shattered by the deafening sounds of explosives. The bombardment went on all night, and it was not clear as to which side would prevail in this clash of arms. At daybreak, as the first rays of the sun hit the fort and the fog lifted over the Bay, the American flag was still aloft Fort McHenry, fluttering in the morning breeze. This was the moving sight that inspired Francis Scott Key to compose the Star Spangled Banner.

With the military edge provided by the rockets, the Sultan won a decisive victory over British forces in the Battle of Pollilur in 1780. It was the only major battle that the British lost on Indian soil during their long drawn-out conquest of the Indian subcontinent

The rockets used in the war of 1812 were a takeoff on the rockets captured by the British from Tippu Sultan of Mysore after the fourth Anglo-Mysore war of 1799. The Mysore rockets used a casing of iron unlike the plaster casings that were in common use in European rockets. The metal casing enabled the sustenance of higher pressures in the bore and increased the propulsive power of the rocket. The solid propellant was compacted gunpowder. The Mysore rockets had a range of 2 kilometers which was more than twice the range of the most advanced rockets used by European armies. Attached to the end of the iron barrel was a long bamboo pole with an affixed doubled edged sword as the payload. When launched in clusters, the sword-equipped rockets played havoc with the concentrations of enemy troops.

The late Dr Abdul Kalam, the architect of India’s modern rocket programs, called Tippu Sultan the father of modern rocketry. Tippu was a technology buff and paid special attention to innovation in armament design. There were thousands of rockets in his armory. Platoons of rocket men were attached to each of his regiments. With the military edge provided by the rockets, the Sultan won a decisive victory over British forces in the Battle of Pollilur in 1780. It was the only major battle that the British lost on Indian soil during their long drawn-out conquest of the Indian subcontinent, starting with the Battle of Plassey in Bengal (1757) and ending with the second Anglo-Sikh war in the Punjab (1848-49).

When Tippu Sultan fell during the fourth Anglo-Mysore war of 1799, the British sent some of the captured Mysore rockets to the Royal Laboratory at Woolwich Arsenal in England. A development team led by Colonel Congreve made a systematic study of the rockets using Newton’s laws of motion. Congreve made design improvements to the rockets to make them more stable in flight. The modified Mysore rockets, renamed the Congreve rockets, were used by the British against Napoleon at the Battle of Boulogne in France in 1806. And it was the Congreve rockets that were used by the British to bombard Fort McHenry in Baltimore during the Anglo-American war of 1812.

Thus, it was that the technology invented by an Indian Muslim sultan inspired the national anthem of a great nation, the United States of America, on the other side of the globe. The advances made by the rocket engineers of Tippu Sultan show that as late as the eighteenth century, technological developments in the Muslim world were not far behind those in Europe. Indeed, in some categories they were noticeably ahead. It was only in the nineteenth century that Europe acquired a decisive technological edge over Asia. We offer a few more examples to reinforce this observation.

The Mogul emperor Akbar (d 1605) introduced the matchlock rifle into the Indian armies. The 66-inch barrel of this rifle was made from fine grained superplastic steel, which was tough, fracture resistant and facilitated a finer, more uniform finish in the bore. The stronger material could sustain higher barrel pressures, which together with the long barrel, enabled the extraction of more energy from the products of combustion and imparted a higher velocity to the exiting payload. The matchlock rifle was more than a match for those made in Europe and could take down an enemy soldier at distances of more than 300 yards.

Babur’s armies used a composite bow in their invasion of Delhi (1526). Made from composite layers of wood and animal fiber, the flexed, pre-stressed bows were comparable to the long English bow in their power and range but were considerably lighter, smaller, and faster. The Mogul bow and arrow made the difference in the onward march of their armies through the plains of India. One must note that specialized composite materials are used in modern engineering in the construction of advanced aircraft and space hardware. For instance, I personally directed the use of a large number of advanced composites in the Hubble Space Telescope (1979-82).

Ulugh Beg (1394-1449), a Timurid prince of Central Asia, built a great astronomical observatory, called Gurkhani Zinj, at Samarkand in today’s Uzbekistan. It was one of the largest and most precise observatories in the world at that time. Ulugh Beg was himself a mathematician of repute and he backed up the work at the observatory with the establishment of universities at Samarkand and Bukhara, turning them into world renowned centers of learning in the mathematical and astronomical sciences. Using observations from the observatory, he published a star catalogue called Zij e Sultani which was a giant leap forward upon the earlier works of Ptolemy. He measured the length of the year at 365.257 days and the tilt of the axis of rotation of the earth at 23.52 degrees. These measurements were far more precise than those made a hundred years later in Europe by Copernicus (d 1543). Ulugh Beg’s accurate tables of sines and tangents were correct to eight decimal places. The work of Ulugh Beg found a resonance in the Taqi Uddin observatory of Istanbul (1574) and the string of observatories built by Raja Jai Singh of Amber (1688-1743) during the reign of Mogul emperor Mohammed Shah (d 1748). One of these observatories, called Jantar Mantar, stands in the heart of the modern metropolis of Delhi.

These examples confirm that mathematical pursuits and technological achievements did not cease with the Mongol invasions. The Ottoman, Safavid and Mogul empires that emerged after the Mongol-Tartar invasions produced a galaxy of great architects and civil engineers. The names of the Turkish master architect Mimar Sinan (d 1588) and Ustad Ahmed Lahori (1649), the architect of the Taj Mahal, stand out. The armies of these three empires excelled in metallurgy, military hardware and artillery.

(The author is Director, World Organization for Resource Development and Education, Washington, DC; Director, American Institute of Islamic History and Culture, CA; Member, State Knowledge Commission, Bangalore; and Chairman, Delixus Group)