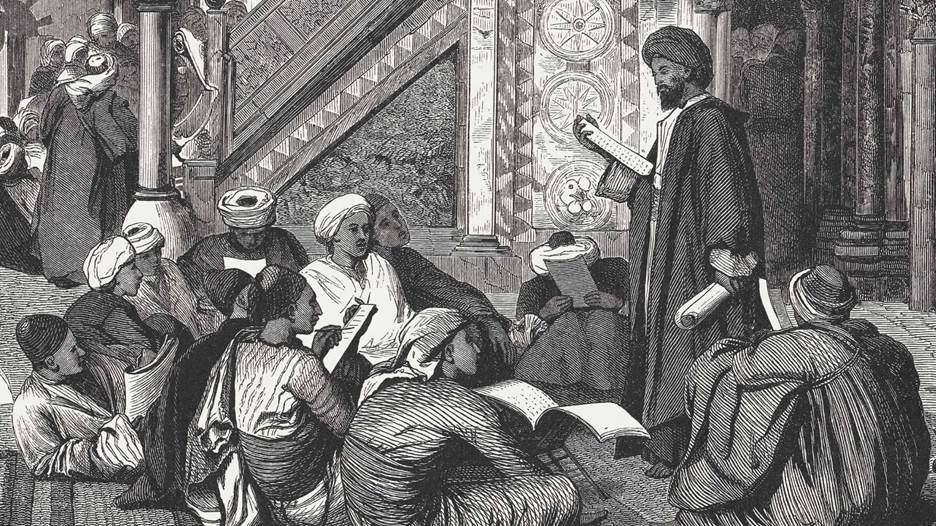

The empire brought together the peoples of Europe, Africa and Asia into a commonwealth of cultures. Baghdad became a melting pot of nations and a crucible of ideas from around the world

Why Did the Scientific Revolution Not Take Place in the Islamic World? - 2

By Professor Nazeer Ahmed

Concord, CA

How did the Islamic world fall behind Europe? Alternately, what explains the rise of European technology and the decay of technology in the Islamic world? Was there one overwhelming event or was it a combination of social, political, technological, religious and military factors? We will take a brief survey of Islamic history to examine the ideas, the movements, the decisive events and the personages who influenced the development of science and technology and contributed to its flourishing and its decline.

The Mu’tazalite Eruption

It was the year 760. The Abbasid Caliphate vaulted across three continents, extending from Spain to India. The Caliph al Mansur (d 775), realizing the need of a new capital for the administration of this vast empire, founded the magnificent city of Baghdad (760) on the banks of the river Tigris in Iraq. The empire brought together the peoples of Europe, Africa and Asia into a commonwealth of cultures. Baghdad became a melting pot of nations and a crucible of ideas from around the world. The resilient and self-confident Islamic civilization amalgamated these ideas and produced a composite culture that preserved and vastly expanded the intellectual horizons of humankind.

Al Mansur started a collection of classical books in Greek and Sanskrit. Under his successors, the process gathered momentum. The famed Caliph Harun al Rasheed, grandson of al Mansur, is generally credited with establishing a Bait al Hikmah (House of Wisdom) to transcribe and translate ancient texts from Greece, India, China and Persia. Under his son al Mamum, the Bait al Hikmah grew into a vast complex with separate departments for the sciences, astronomy, mathematics, logic and medicine.

Here came scholars from around the world with their books and their manuscripts, their philosophies and their sciences. The Greeks brought with them the works of Aristotle, Galen and Plato. The Indians brought the astronomical treatises of Aryabhatta. The Chinese brought the technology for making porcelain and paper. The Persians brought the technology for windmills. An observatory was constructed to measure and map the heavens and measure the movement of planets and stars.

Baghdad radiated a culture of learning. Secondary libraries sprang up in major cities across the far-flung empire, patronized by local governors and wealthy individuals. In later centuries, similar great centers of learning were established in Cordoba, Spain (tenth century) and Cairo, Egypt (eleventh century).

Knowledge is a gift from God. The acquisition of knowledge expands intellectual horizons and provides propulsive power for the advancement of science and civilization. The Arabs mastered the knowledge of the Greeks and Hindus, greatly expanded it and invented new disciplines that were hitherto unknown. The accommodation of the sciences and philosophies from distant lands tested the limits of Muslim intellectual tolerance. Of all the sciences that the Islamic world was exposed to, the rational philosophy of the Greeks presented the greatest opportunity and the greatest challenge.

Muslim scholars fell in love with the rigor and precision of Greek rational thought and set out with enthusiasm to apply it to the profound questions emanating from the domains of nature, science, culture, and faith. The Caliph al-Mansur was so impressed with the power and reach of reason that he adopted the rational approach as the court dogma. Those who applied the rational methods of the Greek philosophers to science, theology and culture were called the Mu’tazalites. This was the heyday for philosophy and philosophers in the Islamic world. Aristotle was their hero, and his method was their guide. For eighty years, from 765 till 846, the Mu’tazalites were the darling of the Abbasid courts.

The Mu’tazalites over-extended their reach, intellectually and politically. Ancient philosophy depended heavily on a linear concept of time. Inherent to Greek logic were the assumptions of before and after, cause and effect, subject and object. As is now well understood by students of quantum mechanics and the theory of relativity, these assumptions are approximations and break down both at the sub-atomic and the galactic levels. The Mu’tazalites were unaware of these limits. When they applied their rational methods to matters of faith, they fell flat on their face. In Islam, God is transcendent, beyond time and space, and there is none like unto Him. To maintain this transcendence, the Mu’tazalites advanced the position that the Qur’an could not be co-extant with God and must therefore be construed as “created”. This is a classic example of how philosophers fall into conceptual traps when they take positions on the nature of things without understanding the assumptions and the limits of their positions. For instance, can rational thought explain love? What is the reason to love? Is love eternal? The heart admits of dimensions beyond the space-time dimensions of the mind. In a larger framework, the mind is king of the created world, but it cannot understand matters of the heart and is helpless before it. The Nobel Laureate Schroedinger in his book Mind and Matter explained it beautifully:

“Mind, for anything perception can compass, goes therefore in our spatial world more ghostly than a ghost. Invisible, intangible, it is a thing not even of outline; it is not a ‘thing’. It remains without sensual confirmation and remains without it forever…. Physical science faces us with the impasse that mind per se cannot move a finger of a hand. Then the impasse meets us. The blank of the ‘how’ of mind’s leverage on matter…is unknown”, Schroedinger, Mind and Matter, Cambridge University Press, 1958, pp 42-43.

Faith, which is based both on reason and emotion, transcends the capabilities of the mind. Modern string theories now admit of eleven-dimensional space and the possibilities of co-extant parallel universes. The limitations of ancient philosophical thought are all too obvious.

The Mu’tazalite position that the Qur’an was “created” produced an uproar in orthodox circles. A counter-Mu’tazila movement sprang up, led by the Usuli ulema. The Mu’tazalites as well as the opposition invoked the Qur’an to justify their positions. Chief among those who opposed the Mutazalites was Imam Ahmed ibn Hanbal, after whom the Hanbali fiqh is named. The Mu’tazalites showed little political wisdom. They applied the whip to those who opposed them. Imam Ahmed was whipped and jailed many times. Faced with determined opposition, the Caliph al Mutawakkil abandoned court patronage of the Mu’tazalites (846). In turn, when the anti-Mu’tazalites had the upper hand, they persecuted the Mu’tazalites.

The Aftermath of the Mu’tazalite Eruption

What is significant is that the initial challenge to the Mu’tazalites did not originate from within their own ranks but from the orthodox ulema. The triumph of the usuli schools ensured the pre-eminence of the orthodox religious elements in the spectrum of Islamic knowledge. It also made the pursuit of philosophy suspect in the minds of the masses and relegated it to the elite and the rulers. Philosophy continued but only as a side show to the primary focus of Islamic civilization on the religious sciences of fiqh (800-850 CE), hadith (800-950 CE) and tasawwuf (1100-1700 CE). In the centuries to come, those who continued to pursue philosophy and science had to look over their shoulders to guard their flank from the religious right. Philosophy and science both suffered.

The crux of the issue was a failure to understand the limits of each branch of knowledge. Philosophy is no exception of this rule. Each branch of knowledge searches for the truth but the ultimate Truth eludes certainty. God is the Truth (Allahu Haq). In other words, the essence of the Truth transcends space-time. Indeed, it transcends human comprehension. This uncertainty principle is stated in different ways by physicists, the mathematicians, the philosophers and people of faith. The error of the Mu’tazalites was to express this uncertainty principle through logic, in space-time. The error of the usuli ulema was to reject philosophy along with the positions taken by the philosophers. It was literally the case of “throwing out the baby with the bath water”.

(The author is Director, World Organization for Resource Development and Education, Washington, DC; Director, American Institute of Islamic History and Culture, CA; Member, State Knowledge Commission, Bangalore; and Chairman, Delixus Group)