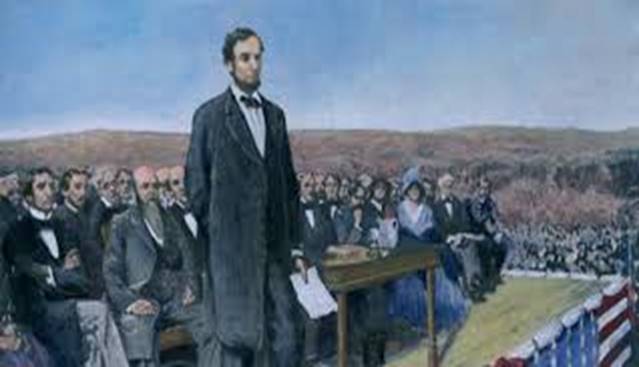

In the famous Gettysburg address, President Lincoln had paid tribute to the fallen soldiers “who had given the last full measure of their devotion” to their country. Should Jinnah’s Pakistan not expect the same from us? -- P hoto Law and Liberty

What Is Wrong with Us?

By Dr Asif Javed

Williamsport, PA

The other day, as I sat with two Pakistani friends—both physicians--a question was asked: what is the language of Pakistan’s national anthem? Neither knew the answer. During my last visit to Pakistan, as I spent a solid hour in perhaps the biggest bookshop in Lahore, there were hardly any customers. The culture of reading has vanished. Sadly, it has been replaced by the abuse of cellular phone, internet, and cable TV.

A young and bright physician, who visited us recently from Lahore, made a passing remark that there is not much to do in Lahore except to eat out. I pointed out that Lahore still has many libraries. He appeared surprised as I pointed out a few names, Punjab Public Library among them.

As we left the bookshop mentioned earlier, my nephew reminded me that it was lunch time. I asked him to find any restaurant in the area that he liked. We stopped at two; both were full of customers with long lines stretching almost to the entrance. It then occurred to me that food has taken a high place in our priorities. Once our visibly overweight PM recently made headlines: on a tour of Sindh, where scores had died of starvation, he complained of the lack of a certain dish.

Our favorite pastime is “loose talk syndrome.” I once heard a gentleman in a gathering, making a blank statement that everyone of Pakistan’s rulers had been corrupt; everyone agreed. Someone reminded them that the curse of corruption did not always exist in our rulers. He then mentioned a few names—Liaquat Ali Khan, Khwaja Nazamudin, Junejo. Even despised Yahya Khan was not financially corrupt. The conversation ended on a sour note. The loose talk has become endemic. Regrettably, we talk too much and often talk nonsense. Part of the problem is that we have moved away from reading. Internet and TV are poor substitutes for good reading. Most well to do, educated, upper middle-class families — in US and Pakistan — have flat screen TV, good cars, and expensive furniture; only a few have a decent collection of books.

Many years ago, I met a Pakistani physician at the Lahore airport. As we exchanged pleasantries, I asked him about his family: with no hesitation, he said that he was divorced. Mian Abbas was one of the co-accused in the Kasoori murder case along with Z. A. Bhutto. Just before being hanged, as his last will was read out to him, he pointed out a minor mistake he wanted to be corrected. I never met Mian Abbas and I have not seen that physician since. But I continue to admire both for the same reason: they were precise and truthful; neither was a loose talker.

Insensitivity to others' feelings is common. People boast of their luxurious lifestyle, oblivious to the fact that some of us may be hand to mouth.

Safar Waseela Zafar is a famous proverb. Among us, those who can afford, often do so but rarely deviate from a set pattern. The religious minded keep going for Hajj and Umra — a friend has been to Saudi Arabia so many times that I have lost count; some travel for better weather; others, for shopping or entertainment; only a few travel to learn and explore. Mark Twain is credited with the saying: “Travel is fetal to bigotry, prejudice and narrow-mindedness and many of our people need it sorely on these accounts. Broad, wholesome, charitable views of men and things cannot be acquired by vegetating in one little corner of the earth all one’s lifetime.” The acclaimed American writer had travelled to most continents. In the1890’s, he went off to India and travelled all the way to Rawalpindi from Bombay and Delhi before writing his famous travelogue.

But the mother of all curses is time wasting. It is mind-boggling that despite living in the West, where punctuality is the norm, we do not acquire it. I used to work with an American physician whose work started at 6 am. He was late just once -- in eight years. The CEO of my hospital was expected at a meeting. As the time approached, he was nowhere to be seen; that is until, he made a frantic call from outside the hospital; he was getting delayed in traffic and asked that proceedings should start, on time, without him. Back home, a parliamentary delegation from Pakistan was recently unable to see the speaker of Lok Sabha at Delhi: the reason: they were late by fifteen minutes; the speaker refused to see them. If true, this speaks volumes about our representatives.

“India’s new religion must be based on a work-ethic---We must not waste time,” writes recently deceased Indian writer Khushwant Singh. He, a Sikh, then goes on to quote a Hadith of Prophet Mohammed which says: “La tasabuddhara; Hoo wallahoo”—don’t waste time; time is God.

Gen K.M. Arif who spent years working with Zia-ul-Huq, has made scathing remarks about his Chief’s work ethics: Zia had made it a habit to delay reading files. Arif writes that Zia needed repeated reminders to finish his work. For those whose files were stuck on the CMLA’s desk, it would have been little consolation that he rarely missed his Tahajjud prayer. Bhutto once kept the whole cabinet waiting for hours while he was nowhere to be seen. A tired J. A. Rahim left; his remark, made in frustration, was conveyed to Bhutto; the result was a real thumping for Rahim by FSF and the loss of one of the few intellectuals for Bhutto. This ugly episode started with time wasting.

Economy with the truth is another problem. The highly educated are not immune from it. A case in point: when I was a student at Govt College, Lahore (1972-74), our Principal who was an acclaimed writer and a poet, had lost control of the students. There were frequent strikes and student unrest. He just was not cut out to be a good administrator. After two years, he was replaced; almost overnight, the order was restored. I came across his autobiography recently; he claims to have done a great job at the Government College.

Some of us just hate to work. The founder of Pakistan was a hardworking man; he did not slow down despite being old and sick. He is credited with the saying, work, work, and work. As for us, a fellow Pakistani American was envious of someone recently who rarely goes to work and still gets paid. I recall a scene from Lahore that remains etched in my mind: men lined up outside Bhatti Gate. I was told that they came from outside the city every day, hoping to be hired by someone for the day so that there was bread on the table for their children. I shudder to think what happens otherwise.

Back in the 70’s, an old man had come from a village to pursue his case in the court. Being told that the hearing had been adjourned yet again for the umpteenth time, the dejected Pakistani raised his hands towards the sky and was overheard saying, “Waa Angraiz, tera raaj”—O, British, I miss your times. The pain of that statement still haunts me. Two generations later, lawyers in Pakistan still find reasons to strike often while the judges are in no hurry to dispose of their cases. That old petitioner is presumably long dead but his heir may still be waiting for justice.

Back in the 90’s, I visited some friends in Pakistan. Over breakfast, as we chatted, I realized that they—a police officer, a magistrate and a district surgeon--were getting late for work. Since none of them appeared to be in a hurry, I tried to remind them. None of them moved. “The work can wait,” said one with a smile; the others agreed. The chat continued.

An old classmate of mine came to the US and called me from Washington DC. I was delighted to hear from him and invited him to stay with me. I was unable to leave my clinic, however. My inability to bring him from Washington offended him so much that he abruptly changed his plans. I do not think he understood the concept of job responsibility. That was the end of our friendship.

When I was a junior doctor at Mayo Hospital, Lahore, our professor had the reputation of being a superb clinician. He had been the best graduate of his class and had a picture receiving a gold medal from Ayub Khan proudly displayed in his clinic. Later, he retired as Principal of King Edward Medical College. But he was infamous for another reason: he rarely made rounds. Most of the patients from his ward left the hospital without ever seeing him. He would turn up typically around 10-11 am, would consume tea in his office, would ask the registrar if everything was ok, and then see a couple of VIP patients before disappearing to his private clinic.

Corruption is not new in Pakistan. What is shocking is its acceptance. While waiting to board a flight to Pakistan at JFK, I spoke to a lady whose brother was a police officer in Pakistan. When asked how he was, she said: “He has just returned from Okara and is very happy, having made a lot of maal.” As I looked, there was sheer joy on her face. An acquaintance of mine had his son engaged to the daughter of a police officer. Someone asked the soon-to-be father-in-law, “What is your son’s fiancée bringing?” Three crores, was the happy answer. So, there it is.

In the heart of London lies Trafalgar Square with the column of Lord Nelson, one of the great heroes of Great Britain. Nelson had won a famous naval victory against France that saved Britain from invasion. Nelson’s final signal before the battle has since become part of English folklore: “England expects that every man will do his duty.” In the famous Gettysburg address, President Lincoln had paid tribute to the fallen soldiers “who had given the last full measure of their devotion” to their country. Should Jinnah’s Pakistan not expect the same from us?